My mother never opened the prayer book I bought for her. She kept it in the guest room, where my wife and I slept whenever we’d visit her in New Jersey.

*

An hour after we had fallen asleep in the guest room, I was awakened by the sound of my mother weeping in the living room. I got up to see what was going on. My father had been in the hospital for nearly three weeks. He was about to be discharged. We made arrangements to move him into an assisted living facility, under the care of hospice. At the beginning of what turned out to be his final hospital stay, my mother was convinced he would be coming home. Now she was crying, crying to God. Please take him quickly. God, please take him quickly. I don’t think I’d ever heard her talk to God before. I sat on the couch beside her. I put my arm around her.

*

The night before my dad died, my wife and I visited him in hospice. We brought the prayer book, Mishkan T’filah, with us. Heavily medicated, he was sleeping peacefully. Before we turned on the television to his beloved Phillies who were playing the Braves that night—they lost, 7-2—, we chanted some of the evening prayers at his bedside. The hospice nurse told us that though he wouldn’t wake up again, he’d probably hear and recognize our voices.

We sang ahavat olam, everlasting love, and I thanked my father for the love he offered me throughout my life. We sang the Sh’ma, Hear, O Israel, and I told my dad that I was here by his side and that I hoped he could hear our voices, my wife’s and mine. We sang hashkiveinu l’shalom, and I thanked my dad for providing a home in which I could lie down in peace at night. My dad wasn’t one for prayer. He may have found more comfort at the sound of the Phillies game, despite their losing performance, which we turned on at a high volume after we closed the prayer book.

*

The title, Mishkan T’filah, comes from this verse: “And let them build Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them” (Exodus 25:8). “Mishkan T’filah,” write Rabbis Elyse D. Frishman and Peter S. Knobel, editor and chair of the editorial committee respectively, “is a dwelling place for prayer, one that moves with us wherever we might be physically or spiritually.”

Mishkan T’filah replaced the Reform movement’s previous prayer book, Gates of Prayer, which itself had replaced its predecessor, The Union Prayer Book. That’s the one I grew up with, The Union Prayer Book, and abandoned shortly after I became a bar mitzvah.

Unlike its predecessors, Mishkan T’filah is a thick, 694-page-long, weighty book. The Kindle version is light. But a digital version of a prayer book, no matter how portable, is not a dwelling place.

*

By the time Mishkan T’filah, the Reform Movement’s prayer book, was introduced in 2007, my mother’s involvement with Temple Emanuel was slowing down.

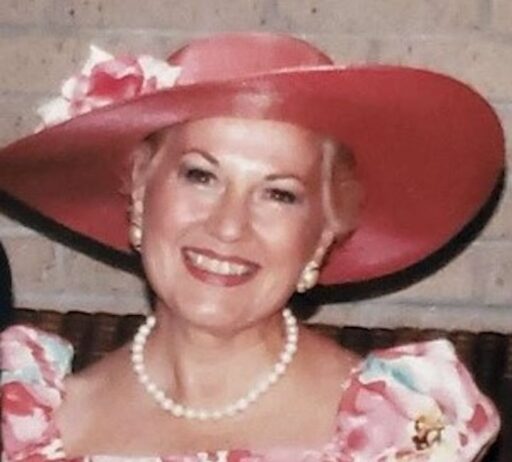

My mother was seventy-six years old the year Mishkan T’filah was published. She had been deeply involved with the Temple for decades, serving in many leadership roles. She chaired the Temple’s ritual committee for 27 twenty-seven years. And she served as its president for three years, the first woman ever to hold that position—indeed, the first woman in South Jersey to serve as president of a major synagogue. As president, she had the privilege and honor of sitting on the bima, the raised platform from which services are conducted and the Torah is chanted, on the Jewish High Holidays. She was famous in the Temple for her stylish dress, especially the dramatic red hats she wore. By the time the new prayer book was introduced, mom had mostly stopped attending Friday night and high holiday services. She didn’t feel safe driving at night. And she was spending more time caring for my dad.

*

After my father died in 2021, my mother withdrew from the world. More than once she called one of my brothers or me at night, often after 10 p.m., crying, inconsolable. No one should live this long, she’d say. What am I going to do, she’d ask.

Had she gone into the guest room and removed Mishkan T’filah from the shelf, would she have stumbled on the hashkiveinu prayer?

Grant, O God, that we lie down in peace, and raise us up, our Guardian, to life renewed. Spread over us the shelter of Your peace. . . . For You, God, watch over us and deliver us. For You, God, are gracious and merciful. Guard our going and coming, to life and to peace, evermore.

*

It’s not true that I hadn’t heard her pray before the night she cried out to God. Until I abandoned, briefly as it turned out, Judaism, I sat beside her at Temple. Then, I paid as little attention to her at prayer as I did to the prayers themselves.

*

I didn’t have Jessica Jacobs’s poem “Kaddish for the Living” to comfort me when my mother’s condition worsened: crying uncontrollably night and day. She was virtually unreachable. She’d stop crying only long enough to ask, when am I going to die. Other than her body, much of her had already died.

. . . my mother is dead but not: the automatic operations lost—driving, turning on a stove, following a plot—while the ingrained etiquette remains. Lawyer-wife-mother no longer yet still a sweet shadow in the soundtrack of every call home. In the Mourner’s Kaddish, death is not mentioned, just praise and petitions for peace. Though only noon, I tuck her into bed. And though she breathes beside me, I am saying goodbye. There is so much guilt in my grief. But, oh I mourn her, I mourner, while I still hold her in my arms. While I fit my body to hers. Like a cloak. Like a shield. Like she taught me.

It doesn’t matter that the particulars—Jessica’s mother’s and mine—differ. The story’s the same: mourning over the death of a mother whose body is still alive.

*

Had she opened the prayer book, maybe my mother would have turned to Psalm 23. Maybe it would have comforted her.

At her memorial service, I read an interpretive translation of the Psalm, written by Norman Fischer. In it, Norman substitutes the second person pronoun for the name “God.” “God” is complicated for many people, “you” maybe less so.

You are my shepherd, I am content You lead me to rest in the sweet grasses To lie down by the quiet waters And I am refreshed You lead me down the right path The path that unwinds in the pattern of your name And even if I walk through the valley of the shadow of death I will not fear For you are with me . . . Surely my cup is overflowing And goodness and kindness will follow me All the days of my life And in the long days beyond I will always live in your house

*

Yes, you, mother. Your house.

*

One day, we’ll scatter her ashes.

Her bones have no dwelling place on this earth.

*

Prayers in a prayer book that’s never opened: if one listens deeply enough, might one nonetheless hear them, speaking in a “still, small voice”?

By heart, I know the prayers. It’s your voice, mother, I’m listening for now.

Richard Chess has published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. Professor emeritus from UNC Asheville, where he directed the Center for Jewish Studies for 30 years, Chess serves on the boards of Yetzirah: A Hearth for Jewish Poetry and Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, where he co-directs its Faith in Arts project. You can find him at www.richardchess.com .