“This Encircling Compassion”: A Goy Puts Me Back in Mother’s Arms

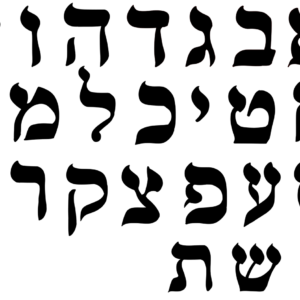

Mother is gone, but compassion is still here. “[T]his encircling compassion,” Brian Volck calls it, rachamim, in his as-of-yet unpublished poem “A Goy’s Guide to TANAKH Hebrew: Rachamim.” Tanakh is the acronym for Torah (The Five Books of Moses), which with Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings), are the three major parts that make up the Hebrew Bible.