They arrived carefully packed in a small box: my share of mother’s ashes. Also in the box, her costume jewelry. An elegant woman, she was. But she didn’t wear expensive jewelry.

*

I didn’t want to open the box until my wife had returned home. She was out tutoring an English-as-a-Second-Language student. I also wondered: what kind of ritual would sanctify the experience of receiving a mother’s ashes?

We usually drop the day’s mail on the kitchen counter to sort later. But it didn’t feel right to leave this package unceremoniously there, where we serve meals to friends who join us for Shabbat dinners. I placed the box on a bench in the den.

*

Before she died, I’d sit with my mother—from a distance; 614 miles to be exact—in meditation. I never told her about this. I visualized her in bed, family portraits hanging on the wall above her head, an oxygen concentrator’s long tube snaking from the living room into the bedroom, the cannula hooked over her ears, its tips resting at the entrance to her nostrils. From the meditation bench on which I sat, eyes closed, I offered her the Priestly Blessings.

May the LORD bless you and protect you!

May the LORD deal kindly and graciously with you!

May the LORD bestow God’s favor upon you and grant you peace!

She was suffering. Alone and afraid, especially at night, not infrequently she would phone me or one of my brothers in tears. I just wanted to hear the voice of someone who loves me, she’d say, apologizing for troubling us late at night. It was easy to offer the priestly blessings to her then. Yawair YHVH panav eilechaw, I’d say, may YHVH’s face shine upon you. That is, may the light of God’s smile comfort and brighten you.

*

Her smile.

Visiting her, I witnessed her stubborn insistence on lurching herself (she refused my assistance) to the bathroom sink to apply her makeup before leaving the apartment. She was too weak to stand. She moaned as she propped herself up on her walker at the sink, her legs trembling. Blush, bold red lipstick. Even on days when she was miserable in her apartment, when she was downstairs with her few friends she smiled. And she’d smile when the nurses passed by the small library where she and a few other women sat playing mahjong. “Betwixt the Cradle & Grave,” writes William Blake in his poem “The Smile,” is one smile that “when it once is Smild/Theres an end to all Misery.” My mother’s smile brightened the room. Perhaps it brought about a pause to misery, that of others as well as her own.

*

Yes, those days it was easy to pray for her, that she would be protected, dealt with kindly, granted peace. And it was painful to sit in meditation and prayer knowing that there was little or nothing that I or, apparently, anyone else could do to ease her suffering.

*

Though it may be powerless, prayer—unlike my mother—survives. In that, it’s like poetry. “[P]oetry makes nothing happen: it survives,” writes Auden in his famous elegy, “In Memory of W. B. Yeats”.

You were silly like us; your gift survived it all: The parish of rich women, physical decay, Yourself. Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry. Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still, For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives In the valley of its making where executives Would never want to tamper, flows on south From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs, Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives, A way of happening, a mouth.

Prayer, too, is “a way of happening, a mouth,” whether it’s spoken, chanted, sung aloud, or uttered and heard as inner speech.

*

“How do you listen for a sound you’ve never heard?”, asks Jessica Jacobs in the conclusion of her poem “Ordinary Immanence.” The poem begins with Jacobs recalling a recurring dream in a New York City apartment, three stories up from a crowded, bustling city street. There, she dreams of a door in the back of her “cramped apartment.”

…I’d press my ear to it and hear the cavernous echo of air arcing through hidden, innumerable rooms, rooms I owned but had never entered.

Years later, in a place far—physically, culturally—from New York City, Jacobs looks up from a book, distracted by the sounds of a garbage truck “rumbling” its way through her neighborhood, and knows

that I want to believe in God. Just like that—a new door in a room I thought I knew by heart.

When she presses her ear to that door, she hears

…the crackling hum of lightbulbs above, the tissued whisper of an iris opening, the deep breathing of the daily world–nothing from the other side.

The poem concludes,

How do you listen for a sound you’ve never heard? Or, more precisely, for a sound you know so well you’ve never heard it?

*

My mother’s ashes: speechless. Or maybe I haven’t learned yet how to listen to them.

*

In the days after she was gone, I again sat with my mother in meditation. I didn’t have to travel far—in my visualization—to reach her. She was no longer in South Jersey. She knew she wouldn’t be there after she died. She said so in “Mom & Dad’s Final Wishes,” a note she hung on her refrigerator.

“The thing that’s most important to us,” she wrote, “is not to burden any of you with cemetery arrangements or feeling any need to visit us there. We won’t be there, so please just think of us once in a while wherever you are.”

*

“Just because we think people have disappeared, doesn’t mean they have. They are closer than we think.” Sara, the second born of twins in Dara Horn’s novel The World to Come, knows something about this. “When twins are in the womb and one of them is born—Sara remembered hearing once—the twin who remains behind watches his sole companion vanish and suffers an agony almost too devastating to bear. Only a moment later, he will understand that his twin has not died, but quite the opposite, that his vanished friend is closer to him than he can know. This, according to a story Sara once heard, is also the way of real death and the world to come.”

*

Not vanished. Close.

Seated on my meditation bench, eyes closed, I sensed her presence. Not her physical presence. Her essence. I offered the blessings to her, praying that God would smile at her now, now that she was free of physical, emotional, spiritual suffering.

Then I opened my eyes.

On my wife’s wrist, one of mother’s bracelets, a bracelet she bought at the Grovewood Gallery when, years ago, she and my father visited us in Asheville.

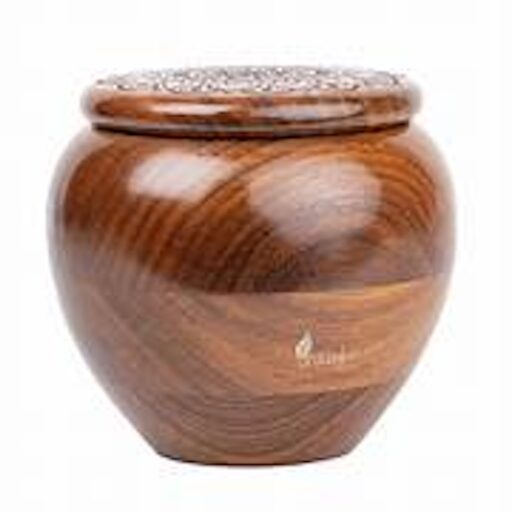

In my study, a handful or two of ashes sealed in a small Ziploc bag.

Richard Chess has published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. Professor emeritus from UNC Asheville, where he directed the Center for Jewish Studies for 30 years, Chess serves on the boards of Yetzirah: A Hearth for Jewish Poetry and Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, where he co-directs its Faith in Arts project. You can find him at www.richardchess.com .