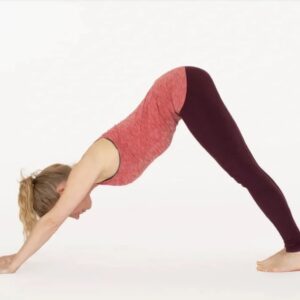

Pissed Off Sun Salutation

We are equal in our mortality: mother, father, me, you, bosses, employees, friends, strangers, enemies. Enemies: I have a hard time believing that anyone is an enemy. A competitor, yes. Wealthier than I am, yes. More talented than I am, yes. More accomplished than I am, yes. Smarter than I am, yes. Jealousy, envy, self-doubt: that’s what I feel when I see others this way.