I remember the apartment in Tzfat. I remember the metal-spring bed frame and cheap mattress, government issue, in which J. did what she did to me, and, when I wept, assured me that nothing issued from me that could lock us together in parenthood. J., newly observant Jew, who, that night and for a few days after, didn’t resist the familiar way of her nights and days up to then, before she separated meat from milk, dark from light.

I remember never asking my roommate, another J., what he heard that night, what he thought as he lay alone on his thin mattress, nor have I asked him since, forty-five years later, if that night played any part in his body becoming a city whose every pulse—traffic signal, sewage spill, blockbuster museum show, steaming hot dog cart—he learned to hold in his awareness.

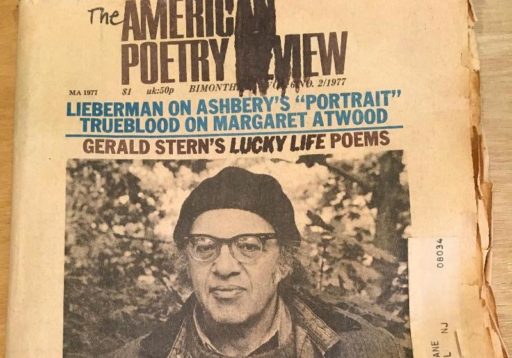

I remember the American Poetry Review, March, 1977, page 26, cows and bald hills of Tennessee and rabbis of Brooklyn, their foreheads “wrinkled” as their “gigantic lips moved / through the five books of ecstasy, grief, and anger.” That’s from “Psalms,” one of twelve poems by Gerald Stern, whose photo on the cover showed his own gigantic, Jewish lips. I didn’t know the psalms yet, though just up the hill from the apartment I was renting in Tzfat, home of the great Sixteenth Century Kabbalists whose graves I frequented that year, 144 rabbis at that very hour were moving their lips and with their fingers drawing abstract shapes in the air as they sang, back and forth with their partners, oral law and sages’ arguments that twisted through a thousand years. And I didn’t know that in twelve years I would live not far from those hills in Tennessee or that, every morning, before I filled my bowl with cereal, I would read one psalm to start the day.

But Jerry took me back to the one thing I did know, Holgate on Long Beach Island at the Jersey Shore! Not long before I flew with sixty-nine other volunteers to Tel Aviv, I spent a night, crashed out on Quaaludes, sleeping in a pale blue Beetle in a stranger’s driveway on Long Beach Island.

Our pockets bulging with tips, we’d driven, J.—my life is lived with J’s—and I, after clocking out at Steak and Brew, the fifty-five miles to the shore. When in the morning she opened the door to pick up the Philadelphia Inquirer from the porch, the homeowner shrieked and we fired up the Volkswagen and fled to the southern tip of the island, Holgate. I don’t remember if we ever changed out of our NY strip scented uniforms or what if anything we did behind the dunes, just that the crisis of our relationship lay with us on the sand that morning.

“Each year I go down to the island I add / one more year to the darkness,” Jerry writes on page 27.

This year was a crisis. I knew it when we pulled the car onto the sand and looked for the key. I knew it when we walked up the outside steps and opened the hot icebox and began the struggle with swollen drawers and I knew it when we laid out the sheets and separated the clothes into piles and I knew it when we made our first rush onto the beach and I knew it when we finally sat on the porch with coffee cups shaking in our hands.

I knew a little Hebrew by then, enough to understand lekh lekhah, go to yourself. I didn’t know how far I’d have to go to feel whole again after the smashed dishes and betrayals and shame. For an hour I thought sex was the map I should follow home. I was more than a boy, less than a man.

“Dear waves, what will you do for me this year?,” Jerry asks.

Will you drown out my scream? Will you let me rise through the fog? Will you fill me with that old salt feeling? Will you let me take my long steps in the cold sand?

I wasn’t interested in becoming an observant Jew. It was still a few months before a Jerusalemite would turn to me, as we sat on a rock overlooking the famous cemetery in Tzfat where Isaac Luria and other giants of Kabbalah still reveal secrets of Torah to those who know how to listen, and say, I don’t think you are ready to return…. I don’t remember if he said to the States or home. Father and mother were eager to pick me up at JFK in a week. I canceled my flight.

I didn’t yet understand teshuvah. The Christ-in-me kept telling me to repent. Decades later he shouts the same thing from billboards all over the American South. Teshuvah: turning, returning.

That’s what she was trying to do, J.: turn away from, turn toward, return to the ground of being, her being, Jewish being. Blessed is God who made me a Jew.

Lucky life is like this. Lucky there is an ocean to come to. Lucky you can judge yourself in this water. Lucky the waves are cold enough to wash out the meanness. Lucky you can be purified over and over again. Lucky there is the same cleanliness for everyone. Lucky life is like that. Lucky life. Oh lucky life. Oh lucky lucky life. Lucky life.

I remember the ocean. I remembered it then, and I remember it now, here in the mountains, 280 miles from my mikvah, the Atlantic Ocean. Once a year, I give my bones, my brain, all the secrets I’ve kept in my cells—full immersion—`to its cold, salt heart, saying my improvised prayer to my imagined god. I don’t know if it’s kosher, if the rabbis of Tzfat or Asheville or Cherry Hill would approve. I’ll let Jerry Stern be my rabbi. You could, too, Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, atheist, agnostic, or Jew.

I still have that issue of APR, its paper brittle, one day to flake away. And I remember you, Jerry Stern, arriving at my apartment in Tzfat.

Richard Chess directed the Center for Jewish Studies at UNC Asheville for 30 years. He helps lead UNC Asheville’s contemplative inquiry initiative. He is a board member for the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. He’s published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. You can find him at http://www.richardchess.com