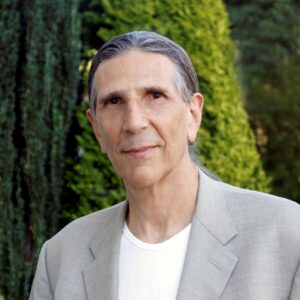

Bret Lott on Food and Hope and the Holy Land

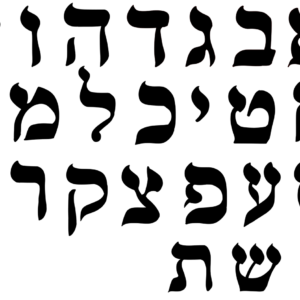

Since October 7, 2023, the world has been focused on the Holy Land. And not in a positive or hopeful way. So what better time for Bret Lott’s latest book—Gather the Olives: On Food and Hope and the Holy Land—to come out? As he notes in his foreword, Lott delivered the manuscript to his publisher in the summer of 2023, when it was possible to find in Israel the subtitle’s “hope.” And find it he does.