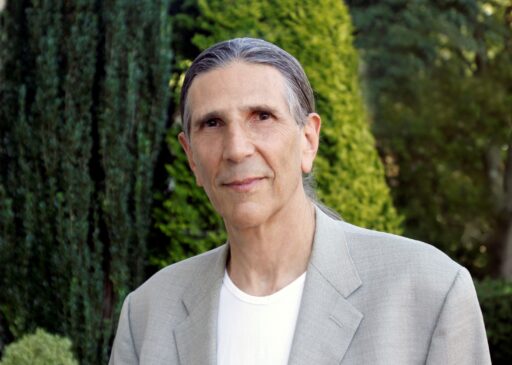

We recently spoke with poet Richard Michelson about his new Slant book, Sleeping as Fast as I Can

Your work overflows with compassion and tenderness, yet these poems seem to have a darker vision than those in your previous books. Is this something you were aware of while putting the collection together?

How could the poems not be darker? Since my last collection, More Money than God, was published in 2016, we have seen the arc of justice bend in ways I—and most of us— did not anticipate: Trump, the virus, democracy teetering on the edge, an explosion of gun violence and hate speech. I am reminded of the old joke: What is the difference between a Jewish optimist and a Jewish pessimist? The pessimist thinks things can’t get any worse, and the optimist says yes, they can.

While my poems have often explored early Jewish history and the Holocaust, and I tend to see anti-Semitism everywhere, even I was caught off guard by the increase in violence against Jews in the past few years. I soothe myself by trusting that rationality will triumph, but am I not then among those who ignored the growing crescendo of hate in 1930s Germany? I go about my days as if it can’t happen here, while history teaches us differently.

And yet, there is no shortage of humor in your work.

Humor is how Jews have learned to survive. Yet when everything becomes a joke, or when bigots have political power, things stop being funny fairly rapidly.

But the act of writing is, in itself, intrinsically optimistic. We would not put words to paper if we didn’t think there was value in expressing ourselves. There is a pleasure we get from the well-crafted poem, even if it is talking about a death in the family, or mass murder. Will poetry save us? If cultured individuals are not more likely to be kind, why do I find solace in art? Humor is our saving grace.

Mark Doty puts your work in the tradition of the Jewish spiritual comedian, and Martin Espada calls you “tender, outraged and funny as hell.” How do you find the balance?

The poems need to explore humanity in all its complexity. I was speaking with Maurice Sendak while he was working on his picture book, Brundibar (the opera that inmates were forced to perform in Theresienstadt to fool the Red Cross into believing that the arts were flourishing in the camps. We now know that cast members—mostly children—were transported to Auschwitz and gassed after their performance). I knew Ela Weissberger, the woman who played the Cat in the concert prior to liberation, and she had also met with Maurice who, soon after, got a call from another woman who had also sung in the final performance. When Maurice mentioned that he had previously heard from Ela, the woman indignantly stated: ‘Well then you probably won’t want to talk to me. I was just in the chorus. I was a nobody. Ela was the big fancy-schmancy star.’ People are people, with all their grudges, silliness, insecurities and pettiness, and that is what makes us wonderfully human.

Speaking of Sendak, you have also had a very successful career writing for children. How does your approach differ when writing for adults.

In both cases, my primary job is to find the essential word and/or image that does the emotional lifting and creates the “a-ha” moment.

Still, there are differences. When I am writing picture books, I generally have a subject or question in mind before I begin. I know where/when my story/poem will end, and what I am trying to say.

With “adult” poetry I start with a phrase, and let the words lead the dance. I rarely know where I will end up, and I learn what I wanted to say by reading the poem.

There is truth in the fact that children, with fewer cultural references, deal in more basic emotions. And I try to find that emotional core in all my writings.

Childhood ought to be taken more seriously. Prejudice, race, and loss are issues that most kids deal with every day in school. There are those who believe childhood is a time of innocence, but I wonder if they really remember their own childhoods.

You mentioned race, prejudice and loss in your last answer—all things you deal with in your poetry. I don’t see many “White” poets writing so explicitly about race relations.

I am happy to have a debate when/how/whether Jews should identify as White, but that is for a different interview.

Our concerns are our concerns, and I can only write about issues that are daily in my consciousness. I am a political being and my view of life was forged early on. When I was born, my neighborhood in East New York, Brooklyn, was ninety percent Jewish. A short twelve years later it was ninety percent Black, and would soon be majority Latino, sparking my life-long interest in racial and economic issues. I write in this collection at length about the murder of my father, the last Jewish shopkeeper, in a changed neighborhood. Certainly, a big part of why I write is an attempt to heal both society’s ills and the many wounds within myself.

Why do so many of your poems rely on traditional formal structures: sonnets, sestinas, villanelle, and couplets abound?

When I am writing about subjects that touch my emotional life—my mother’s decent into dementia, my father’s murder—the forms help me constrain the passion, which heightens the energy. On a more prosaic level, my mother was a lover of crossword puzzles and word games, and there is definitely an element of challenge and fun for me to work in strict forms. Plus, I just like the way sonnets look on the page. The regularity adds to the visual appeal for me.

Let’s talk about the visual appeal. You have been an art dealer for more than forty-five years. How does that inform your poetry?

Like most writers I have a full-time “day-job.” My job happens to be one I love, and I tend to hang out with visual artists more so than poets. There are many ekphrastic poems in my previous books, Battles and Lullabies and More Money than God. My libretto for the music-theater piece “Dear Edvard” is a collaboration with the composer Steven Schoenberg and based on the life of Edvard Munch. It began as a collaboration with the artist Leonard Baskin. My current collection references Rembrandt, second only to Moses, and Kafka—my holy trinity.

I am a fan of interdisciplinary projects. I’ve collaborated with visual artists, dancers, and composers. I see the genres less as feeding each other than as arising from the same hunger.

The book is heavy on prayer, argument, and accusation. Have you always spoken to God?

Among those few who have “heard of me,” it is most often as the author of Jewish-themed children’s books. So, readers are often surprised to learn that I grew up in a household that rejected religion of any kind. My mother, rebelling against an orthodox upbringing, was an avowed atheist to the end (as she says in Unveiling, “No soul, but soil” after burial). When I met and married a Methodist, I insisted on a Civil ceremony. It wasn’t until she was pregnant with our first child that Jennifer decided to convert to Judaism. It was during her studies that I realized how little I understood about my own heritage. To get back to your question, my wife believes in prayer; I am more comfortable with argument and accusation.

Let’s end by circling back to the beginning. Do you consider yourself a Jewish poet? A religious poet? A political poet? What do you hope readers take away from this book?

Yes. No. Yes. No idea.

I don’t expect my poems to save the world but at least let my words do no harm. Let each be a small seed of laughter, truth, or peace planted in the endless universe.