How do we know?

O Lord, You search me out and know me. (Psalm 139, trans. James Kugel)

How do we know what the Lord knows?

*

One Friday afternoon, as we turned into Kingston Estates, mother asked, do you have something you want to tell me. No, I said. Are you sure you don’t have anything to tell me, she asked again as we turned onto Drake Road, our street. No, I said. A few days earlier, I told my friend Bruce. Leaning against the hood of my mother’s Oldsmobile Cutlass, I kissed Robin, a girl in our neighborhood. Bruce had already kissed a girl. This was my first kiss. We were waiting in my garage, Bruce and I, to be picked up for Sunday school at Temple Emanuel. I was 12, a bar mitzvah student. Before we pulled into the driveway, mother said, if you don’t have anything to tell me, then you can’t go out tonight. How did she know? Was she listening to us from the other side of the door into the garage? I wanted to hide. That kiss was mine, not mother’s.

Where can I go from Your spirit, or how can I get away from You?

I kissed a girl, I confessed.

I know, she said. You’re not allowed to kiss another girl ever again.

My first transgression.

*

Fall, 1979. After three years in Israel, where I had fled, in part, to escape a failed romantic relationship, I returned home. I moved back into my parents’ house. For a few months, I didn’t have a job. I read, wrote, listened to music, caught up with old friends, daydreamed. And for a minute, I flirted with Orthodoxy, ultra-Orthodoxy, driving weekly into Northeast Philly to study with a Habad rabbi.

One afternoon, I overheard my mother crying to a friend on her bedroom phone. I have to leave him, she said. I was down the hall in my room. The next day, I drove to the Argyle Rooster, a chic French restaurant where I had worked as a waiter before leaving for Israel. I was offered a job, assistant manager. I accepted. I found an apartment close to the restaurant and moved out of my parents’ house for the last time.

I never told her why I suddenly moved. Did she know?

There is not one thing I say that You . . . do not know about.

*

“People who believe in God,” writes James L. Kugel in In the Valley of the Shadow: On the Foundations of Religious Belief, “generally believe (whether they know it or not) in…a semipermeable membrane separating an outside Deity from an inside ‘me.’”

*

When I was two-months old, mother and my birth-father divorced. His parents, born Jewish, converted, before he was born, to Christian Science. I was born with a heart condition. I didn’t think to ask for the actual diagnosis until recently. Endocardial fibroelastosis, mother told me. She was in her late 80s, her memories slowly being erased. That she remembered this effortlessly surprised me. It also left me wondering if it was accurate. I needed medical care to survive. A man of faith, apparently, mother’s first husband did not approve of my receiving medical care. One morning shortly after the divorce, mother wept in the middle of a grocery store aisle. I don’t know if I was with her or at my aunt’s house, where we were living after the divorce. I know only this. I did not cry. My heart wasn’t strong enough, mother was told, to endure the strain of crying. She held me to keep my calm. My heart depended on her.

Mother and son, son and mother: a permeable membrane between us.

*

You slept with my best friend?, I screamed then threw the phone at my bedroom wall. Mother and father were downstairs. A few days later, when she was out, my girlfriend of nearly three years, I entered her house (I had a key), went into her closet, found the expensive dress I had bought for her at a trendy clothing store on South Street in Philly with my tips, and tore it to pieces. Then we broke up. Then mother and father dropped me at the El Al Terminal at JFK airport, where I joined 69 other American Jewish volunteers heading to Israel for a year. Neither father nor mother gave any indication of having heard the phone hit the wall.

*

How we care for one another. What we know and say. What we know and do not say. Sometimes it hurts, sometimes heals.

Why am I thinking about this now?

*

The hour is late.

Mother is 91. My true father, mother’s beloved husband of 63 years, passed away in the Jewish year 5781, a little more than a year ago. To this day, the television comes on to the financial news, his favorite station, no matter what station it was tuned to last, she says. Nights alone are hardest, she says. I FaceTime with her every night. We don’t have much to say to one another.

You probe my thoughts from far off.

She doesn’t share her thoughts. I don’t ask.

The hour is late.

It’s the 29th of Elul, the final day of 5782. Rosh Hashanah begins this evening; Yom Kippur follows in ten days. It’s the season of turning inward, facing our transgressions, asking for forgiveness of each other. And of…

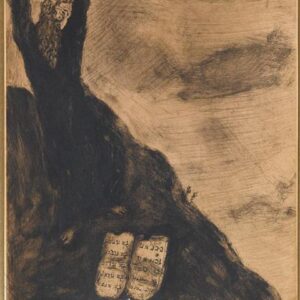

Psalm 139.

O Lord, You search me out and know me.

You know when I am sitting around or getting up. You probe

my thoughts from far off.

You sift my comings and goings; You are familiar with my ways.

There is not one thing I say that You, Lord, do not know about.

In front and in back You press in on me and set Your hand on me.

Even things hidden from myself You know, things that are beyond me.

Permeable: door, wall, phone, screen. We are permeable: skin, skull.

Where can I go from Your spirit, or how can I get away from You?

If I could go up to the sky, there You would be; or down to Sheol, there You are too.

If I took up the wings of a gull to settle at the far end of the sea, even there Your hand would be

leading me, holding me in its grip.

I might think, ‘At least darkness can hide me, nighttime will conceal me.’

But even darkness is not dark for You; night is as bright as the day, and light and dark are the

same.

We are small, we are mortal. So we imagine a Being capable of knowing what we cannot know, of existing beyond the limits of where we can go.

Even a mother cannot know everything about her son. Even a son cannot know everything about his mother. God only knows. We imagine it is so.

Richard Chess directed the Center for Jewish Studies at UNC Asheville for 30 years. He helps lead UNC Asheville’s contemplative inquiry initiative. He is a board member for the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. He’s published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. You can find him at http://www.richardchess.com