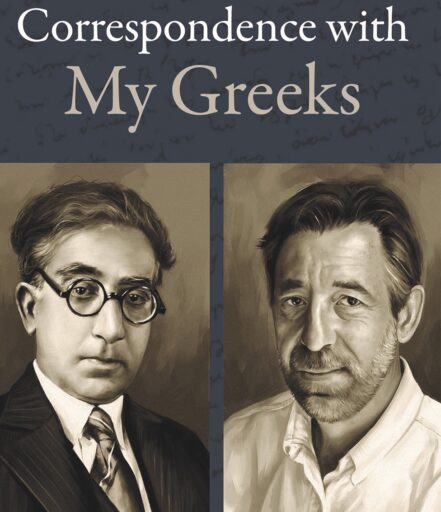

Scott Cairns’s new poetry collection, just published by Slant Books, is called Correspondence with My Greeks. The title is intriguing. “Correspondence,” of course, has a dual meaning: “communicating with” but also “connection or similarity to.” I think both meanings are at play in this collection. Each poem is “After” a particular Greek poet: as Cairns explains in his Introduction, his modern Greek isn’t good enough for him to actually translate these Greek poems. So, instead, he moved “into another dynamic altogether—composition understood as opening my heart and mind to a conversation that both preceded me and will survive me.”

What he gives us in this volume, then, are seventy-eight such conversations (correspondences) as connections. The poems are so various that I can’t possibly treat them all here. But certain motifs and moods strike me. The first I’ll touch on (though, appropriately, these poems are toward the book’s end) is dying and death.

In “Undesired Kiss,” for instance, two families are enjoying the beach. But then—

Regardless, early of an evening in our common campsite, Death’s Angel slipped with cruel intention into the quiet tent where the youngest of us slept. With cruel intention, that unwanted messenger delivered its missive to the infant, whose breath departed with Death’s kiss.

“Words for Irini, My Mother” narrates a slower dying, in one long, luscious sentence:

Once I saw, however, that nothing could woo you back to us, I found a way to ease your determined drop away from us, away from the flowers, the birdsong just audible through the glass, away from my hand smoothing your brow with the cool cloth, away from my last kiss upon your suddenly smooth and luminous brow.

Then there’s this short chilling image in “One Consolation”:

Who can foretell what death will say as it opens the door to the cold?

There are more poems on death in this series. Yet I hasten to add that they’re balanced, throughout the book, by poems expressing hopefulness, beauty, even joy. In fact, just before the death poems we get “Prospect,” with its “cheery prospect” in the midst of the country’s troubles:

Nor do I recall the kosmós before the fall—the alleged fall.… …Instead, I survey the rubble of what had stood, and from that broad expanse of rubble I glimpse through the cloud an untouched, cheery prospect.

Stronger than this cheeriness is the “beauty” detailed in the delicious language of “Capacity”:

Before I close my eyes, I breathe in deeply the flowered air, surveying one more time the world’s extravagant bouquet, array of beauty, ever-present, ever expanding the heart’s slow-waking, surprising capacity.

In “For My Father,” the “beauty” is intensified, linked to “glory”:

The secret life you hid behind your ember eyes has become—I’m guessing here—the secret life my own heart tends, imagining what beauty and what glory will attend our all one day seeing face to face, revealing after all these fraught, withholding generations the trembling aspects of our very selves.

Glory can, of course, burst into joy, which is where “Late Prayer” takes us:

Even if our history is troubled, and the near term appears to be also troubled, promise me that these concerns will remain ineffectual in spoiling the joy of rising from your bed, opening the door, stepping out.

Akin to joy, I’d say, is the verbal fun that Cairns has in many of this volume’s poems. There’s the playfulness of alliteration, interestingly active in the two poems I quoted from at the start of this post (interestingly because these are dark poems, about death). And elsewhere in the book, we get, for instance:

…the grit and grimy matter of the poor clamoring for coins and brilliant goods. (“The City”)

Better—I say— to bide one’s time, to see what manner of beast happens along,… (“No Oracle”)

Or there are the multiple alliterations of “Noetic Core,” which I’ll underline:

One spiraling descent into the fragrant stillness at our core, that noetic cove from which each of us—my every self— calmly observed the riot, the roar, this roiling tumult threatening to erase us all.

There are also poems that are playful in other ways. In “The Democratic State,” the phrase “numbskulls and dipshits” to characterize the state’s rulers is repeated five times. Or take the language-play in “Skin,” from “tender” to “attends” and “momentous” to “not-so-much”:

Lovely, varicolored membrane, the tender of the human skin attends our every moment, attends with equal bearing both the momentous and the not-so-much.

Or the entire poem “Half Past Midnight”:

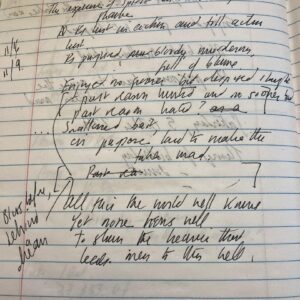

Half-past midnight, unmoving in my chair, my having not so much as cracked the book I hold, nor having so much as lit the lamp adjacent to my arm, I remain intent upon the figure of myself sitting in this same dim room, tucked into a similar chair those many years ago, touched by a similar darkness, and witnessing also a similar despair. When will I become the man that this young man supposed those many years ago? Was he likely ever to arrive? Half-past midnight, I marvel at the rush of hours. Half-past midnight, I wince at the rush of years.

Here there’s the end-line repetition of “having.” There are the three consecutive “similar”s—with the alliterative play of “tucked into a similar” and “touched by a similar.” And the alliteration of “darkness” and “despair.” And of course the near-repetition of the final two lines. How intriguing that the poem’s theme of dim dark despair is presented in language that’s so playful. I’m assuming that the Greek poem that Cairns is adapting here also incorporates this paradox. But it’s Cairns who crafted the English approximations.

As he crafted English approximations—correspondences—for all the poems in this unique and remarkable collection.

Peggy Rosenthal has a PhD in English Literature. Her first published book was Words and Values, a close reading of popular language. Since then she has published widely on the spirituality of poetry, in periodicals such as America, The Christian Century, and Image, and in books that can be found here.