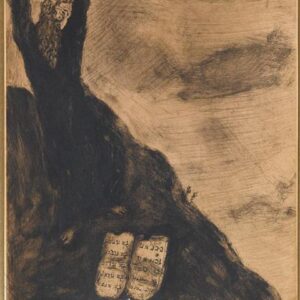

Moses and this Moment

Our mouths, our words, can be used for good or ill, to liberate or enslave, to bless or curse or encourage, to ask difficult questions. We share our stories, so others might be invited to tell their stories in turn, allowing us to not simply scream at and past each other but to see what values we might hold in common, to perhaps one day even arrive at a place of mutual understanding and esteem.