When I got there, mother’s apartment was mostly empty. A dining room table, a wing chair, a particle board desk, a few lamps, a spatula, a cutting board, a corkscrew—stuff to be given away or discarded. Since father’s death a year and a half ago, mother lived there alone. The guest room where my wife and I have comfortably slept whenever we visited was now the staging area for bins of family photos and a stack of files left by my brothers for me, the clean-up man, to sort through.

First file, first document: “Certificate of Registry of Marriage,” March 7, 1953. Name of bride: Shirley Dorothy Scharf. Name of groom: William Austin Rosenblum. My biological father. The second document: “Interlocutory Judgment of Divorce,” September 20, 1954. Plaintiff, Shirley Rosenblum vs. Defendant William A. Rosenblum. That’s all I read that week.

“A summoning from within,” either from a text or one’s self, that’s an experience, writes Peter Cole in his poem “Vav,” that one may have when reading. I can’t say I felt summoned by the official documents. But I did feel drawn back. Drawn back to my beginning. The few facts—the maiden name of my biological paternal grandmother, the name of the rabbi who officiated at my mother’s first wedding, the name of the attorney who represented my mother in the divorce—gave more volume, more definition to all the unknown of those days.

That week, I was also drawn back to love, first love. For eight nights, I stayed with her, the woman who has lived within me since the night I moved the last box of books out of the apartment we briefly shared in Collingswood, New Jersey. Over three years in the mid-1970s, our relationship progressed. At first, we each lived in our parents’ homes. Then, with a few girlfriends she moved into a house in Haddonfield. Finally, we moved in together. With each move, our relationship deepened and at the same time grew more fraught. We loved. We fought. We hurt. We split. A few months later, I graduated from college and fled to Jerusalem. To recover from my loss, I needed to be as far from her as possible. Fled to, yes, but at the same time I was drawn, drawn back home—to Jerusalem, where I had never been before, not in this body, not in this lifetime, not even in my imagination.

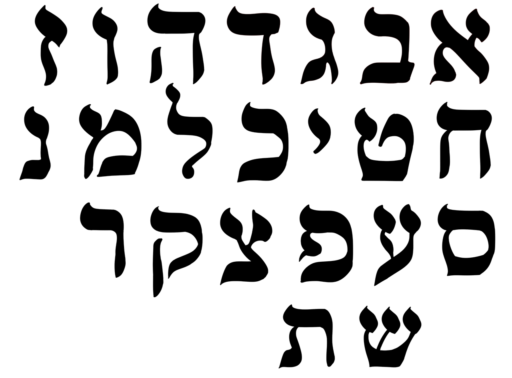

In my imagination, a vav lives in me. I visualize it, the sixth letter of the Hebrew alphabet, along the length of my spine. The other letters of the tetragrammaton, too: yud, the 10th letter, rising like the small flame of an eternal light from the crown of my head; hey, the fifth letter, its roof stretching across my shoulders and its walls protecting each side of my torso, and, following vav, the second hey, its upper line resting on my hips, and its two parallel lines running down the sides of my legs. Yud-Hey-Vav-Hey: created in the image of, I am. I embody the Name, the written name.

From Sefer Yetzirah, the Book of Creation, to the Zohar, the Book of Radiance, to Ben Shahn’s The Alphabet of Creation to Lawrence Kushner’s The Book of Letters, Jews have meditated on the letters of the Hebrew alphabet—their shapes, their names, their sounds, their numerical values—as yet another means of drawing close to Creation, if not the Creator. “For two thousand years before creating the world,” teaches the Zohar, “the blessed Holy One contemplated [the letters of the Hebrew alphabet] and played with them.” Eventually, the Divine formed words and with or through the words created the world.

In his most recent book, Draw Me After, Peter Cole extends the practice of meditating on the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Cole’s poem “Vav” sees the shape of the letter as a metaphor for a reader. The poem then offers a meditation on what happens when a text hooks a reader or a reader hooks a text. The poem is dedicated to the memory of one of the great readers of our time, the literary scholar Geoffrey Hartman.

This upright letter bows its head ever so slightly out of humility (much like Geoffrey) toward the page

it’s fixed itself to as though by a hook or being hooked really a summoning from within

it or him to listen hard to what’s barely there and maybe not-quite yet between the lines

to sit taking a stand and read learning straightness and when to bend so we come not to the End—

but once again and again to And

Where does the vav end and the text, of which it is a part, begin? For that matter, where, in Cole’s poem, does the vav end and the reader begin? Indeed, where does a text, any text, end and a reader begin or a reader end and a text begin?

Before the faculty of memory was formed in me, William Austin Rosenblum ended. Not seen or heard from since September 20, 1954, two months before my first birthday. That’s where I began. As long as I live, W. A. R. lives in me: his genes, his absence. And now, from a great distance, his presence. Not only in Los Angeles County and Superior Court Documents. I found their wedding album, too: Shirley’s and Bill’s. Mother’s first marriage, a mistake.

My first love, which lasted a little longer than mother’s first marriage, was not a mistake. Our recent visit: the first time since 1976 we slept under the same roof, me in the small-guest room that shared a wall with her bedroom where she slept behind a closed door. My wise, trusting wife of thirty-two years suggested I ask her if I could stay with her. It’ll be depressing, Laurie said, to sleep on a mattress on the floor of your mother’s lifeless apartment. When, in the evening’s first dark, I returned from the challenges of escorting mother toward Oblivion, she held me, my friend of nearly fifty years. She listened. She heard. She counseled. She consoled. She held me, but we did not touch. Our visit was intimate, an intimacy made possible by distance.

So, too, the intimacy of reader and poem. The palpable presence of each: letter, word, line, eye, ear, head, spine. The almost boundless distances that draw them toward one another. A failing mother. An absent father. An old love. A poem that does not end.

Richard Chess directed the Center for Jewish Studies at UNC Asheville for 30 years. He helps lead UNC Asheville’s contemplative inquiry initiative. He is a board member for the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. He’s published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. You can find him at http://www.richardchess.com