Because it’s the season, I’m thinking about turning.

I don’t trust my nose. So, my wife smells the 2% milk for me to see if it has turned.

In the supermarket, I’m in a rush. I don’t have time for conversation. So, when I see at the far end of the aisle I’ve just turned down an acquaintance studying the breakfast cereals, I quickly turn around and proceed to an aisle at the far end of the store.

When I see that x is calling, I let the call go to voicemail. I’m afraid to turn down an invitation to dinner.

Lately, I am having a hard time turning away from CNN.

My attention is untamed. Like a moth, a mosquito, a fly, it flits, it darts from one promise of honey, of sweet blood, to the next. From tab to tab it turns: Times of Israel to Gmail to Poetry Daily to…. I should learn to tame it, to discipline it to turn in the direction of something truly fulfilling and sustain it on that sentence, that light, that fragrance, that water, that face until I’ve had my fill, the portion allotted me, and then, with all deliberate intention, turn it to the next life-giving scene.

Every August, long before the official beginning of Fall, my wife says, “the leaves are already turning.” I see what she sees: a few leaves here and there morphing from deep green to washed-out red. No, I say, they aren’t turning yet. It’s at least a month before the leaves will turn.

*

“Ben Bag Bag said: Turn it over, and [again] turn it over, for all is therein. And look into it; And become gray and old therein; And do not move away from it, for you have no better portion than it.” That’s the Jewish sage Ben Bag Bag in Pirkei Avot, “Ethics of Our Fathers,” a well-known section of the Mishnah, Jewish Oral Law.

“It”: Torah, to which we turn and turn and return, each time bringing to it our recent experiences, fresh provocations and threats and challenges and discoveries and pleasures—personal, societal, global, political, environmental, economic, existential. As we bring the fullness of our experience to it, it meets us, offering up new insights, fresh interpretations that speak directly to the ever evolving conditions of our lives. Only by turning to it and turning it over again and again will it remain alive. Otherwise, it will wither, it will die. Like a once great civilization. Thus, turning: interpretation.

*

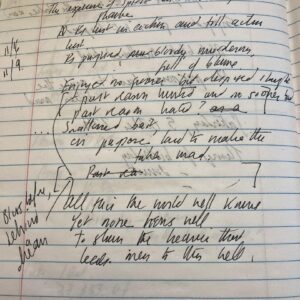

And this: “a high moment of turning.”

Every single instant begins another new year;

Sunlight flashing on water, or plunging into a clearing

In quiet woods announces; the hovering gull proclaims

Even in wide midsummer a point of turning: and fading

Late winter daylight close behind the huddled backs

Of houses close to the edge of town flares up and shatters

As well as any screeching ram’s horn can, wheel

Unbroken, uncomprehended continuity,

Making a starting point of a moment along the way,

Spinning the year about one day’s pivot of change.

But if there is to be a high moment of turning

When a great, autumnal page, say, takes up its curved

Flight in memory’s spaces, and with a final sigh

…subsides

. . .

…then let it come at a time like this

A time like this: Rosh Hashanah. A moment to which John Hollander turns in his poem “At the Jewish New Year.” Within this passage from the poem itself, many turns. For one, the poem’s argument turns from identifying “every single instant” as a turning point to singling out “a time like this” as “a high moment of turning.” For another, the poem’s lineation, in particular the way its lines end, enacts another turning. The first line is end-stopped: “year” followed by a semi-colon. The second line is end-paused: “clearing”. A phrase—”plunging into a clearing”—concludes there without punctuation. The complete clause continues into the next line. The third line ends with a rather soft enjambment: “proclaims.” The fourth line ends with a strong enjambment: “fading.” We can feel the poem speeding up, as, from line to line, it turns away from home (an end-stopped line).

If you look closely enough, you can find other instances of turning in these opening lines of the poem. In the first two lines, the poem’s attention turns from the mind to the eye and ear: “Every single instant begins another new year” (mind); “Sunlight flashing on water, or plunging into a clearing / In quiet woods announces” (eye and ear). In the second and third lines, the poem’s attention turns from water to woods. We can find moments of turning even at the level of syntax: “sunlight flashing” turns to “hovering gull” turns to “fading / Late winter daylight.” A reversal of order in the first case; a turn from a comparatively plain description to a more detailed description.

In his entry for the term “verse,” a synonym for “poem,” in A Poet’s Glossary, Edward Hirsch writes, “The word verse is traditionally thought to derive from the Latin versus, meaning a ‘line,’ ‘row,’ or ‘furrow.’ The metaphor of ‘plough’ for ‘write’ thus dates to antiquity. Verse may alternately derive from the Latin vertere, ‘to turn.’”

Turning: at the heart of the art of poetry.

*

Turning: an, if not the, essential act of Jewish life. Teshuvah, we call it. Repentance, it’s translated. “Teshuvah,” writes Rabbi Alan Lew, is “a Hebrew word that we struggle to translate. We call it repentance. We call it return. We call it a turning. It is all of these things and none of these things. It is a word that points us to the realm beyond language, the realm of pure motion and form.”

*

Today, as I write this, is the first day of the month of Elul on the Hebrew calendar. Elul: a period of turning inward to reflect on our behavior over the course of the year that’s now coming to an end. In a month, I’ll stand before the Divine. Then, among others who engage in this practice, I’ll tremble before the Judge of Judges, the Being who decides who, over the course of the coming year, shall live and who shall die, who by fire, who by water, who shall be serene, who tormented.

To prepare for that fateful moment, I’m turning my attention to “motion and form,” including, and especially, in poetry. A poet can and must choose which way to turn, from word to word, phrase to phase, line to line, stanza to stanza, in a poem. Can’t I do the same in my everyday life? Must I be determined by habit, in particular those habits that decrease rather than enrich life, harm rather than heal? Can I choose, this year, to turn toward friendliness, even when it’s not convenient? Can I turn away from addictive behaviors, such as obsessive watching of the news? Can I turn away from denying physical facts knowable with my eyes?

Because it’s the season, my attention is directed toward turning. If I can sustain my attention on turning, perhaps, like John Hollander at the end of “At the New Year,” I’ll be able to “sing / Thanks for being enabled, again, to begin this instant.”

Richard Chess has published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. Professor emeritus from UNC Asheville, where he directed the Center for Jewish Studies for 30 years, Chess serves on the boards of Yetzirah: A Hearth for Jewish Poetry and Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, where he co-directs its Faith in Arts project. You can find him at www.richardchess.com .