The title poem of Suzanne Nussey’s debut poetry collection, Slow Walk Home, comes at the end of the book’s first section, called “My Father’s House.” This section title has a dual reference: her childhood home plus the church where her father is pastor. In the poem “Slow walk home” (yes, Nussey capitalizes only the first word of each poem’s title), she is a young child walking with her father on his weekly visits to parishioners. On their way back home, she muses ominously “This day / an empty tablet not yet tipped / toward calamity.” Yet her father keeps anything ominous at bay, as the poem ends:

Just now

the face of my father

turned toward me

the blissful season

opening its arms

Come this way, this way, this

Going back to this section’s opening poem, “What came of picking flowers,” we again see her father’s gentle love. A child still, she has found in his shed “gladiolas / in silver pails of water,” her childish imagination seeing the flowers as “miniature angels / the size of my small hand” that “climb bright green swords.” Thinking that flowers should be planted,

I free the perfect flowers

from their metal pails, planting them

in ranks of rebel angels, until

his garden blossoms brilliantly again

and I see my work is good.

But after this fun echo of the Genesis creation narrative (where after each day’s work, “God saw that it was good”), things go downhill for the child—because her father had been keeping the flowers fresh in water to use in an afternoon wedding. When he finds the planted flowers— “Swords listing, wings soiled, fists unfurled, / swooning like a tipsy heavenly host that cannot fly”— and then sees her, hiding and watching, he just “laughs.”

In Slow Walk Home’s second section, titled “Life Skills,” the speaker is now an adult, meditating on married life, pregnancy, breast surgery, metamorphoses. And on dissolutions and death. The shaped poem “On the way out, please close the door behind you” images disappearances. In the first stanza, bodily parts are decaying:

Everything works its way

to naught

relentlessly as surf on stone

bones soften

retinas tear

cells rebel proliferate decay…

The body erodes.

We melt away.

In the second stanza, it’s her children who are severing connections:

So too our flesh and blood

depart, make a plan

to split the instant

they’re conceived

The rift grows subtly…

and all connection

cleaves until

the body

becomes nothing

but another

body’s

thought.

In those spaces between lines, I read disappearances.

And the theme of disappearances continues in the next poem, “Deliquescence,” which images her mother dissolving into death:

Beginning the removal of her

substance from the earth

sweat pearls her brow

imitates her baptism

soaks her cotton gown.

Already she is less

than my mother

dissolving from the small bones

that buoyed her through eight ill seasons.…

Morphine

melts her into senselessness

beyond dreaming. Breath sinks

deeper in her body ebbing

even as she becomes a flood

drowning sheets hair skin

the flannel we have swaddled her in.

Water poured her into life.

Water carries her away.

It’s a dark vision of dying, yet engaging through all the watery images: “sweat… soaked… dissolving… melts… ebbing… flood… drowning.” Then of course the explicitness—almost a summary—of the final two tetrameter lines.

Nussey’s third and final section is titled “Safe Houses.” So in a sense we’re returning to the first section’s “houses”—but with very different referents than her father’s church or her childhood home.

The opening poem, “The music of the house,” begins in Eden—with the “harm / our first parents did / the family home swapped / for a mouthful of fruit…”—

When Uriel placed a fiery sword

at Eden’s gate, we all went packing.

You left for school, married,

took a job down south.

—and suddenly we’ve leapt over two millennia! The speaker continues: “Our correspondence always dwells on home” (with that fun pun on “dwell”), then moves to various houses the family has lived in, then ends by suggesting a difference between a house and a home:

In such places, waywardly

we’ve roamed and hoped

this music of the house

might sing us back to home.

Other poems on houses follow: in memory of a neighbor (“The little houses on our street / fall one by one / to fashion or decay…”); neighborhood changes over time (“friends’ and neighbors’ places filled / by strangers who build / gated homes of glass and stone”; “Lullaby for an empty nester”; “Safe as houses: a litany”—

The little black ants

of April have arrived.

The bricks

need repointing.

—which unexpectedly moves into

Four friends

suffer five different cancers:

ovarian, prostate, breast,

bladder, lung.

And there’s her own cancer, too, in the poem “To my right breast before surgery.” This will be her second mastectomy, as the opening lines make clear: “The left your twin scimitarred / years past…” Then the grim current reality:

Heart sheath

my metaphor

in flesh that lately pleased

my infant and my spouse

and will again be altered

as my hidden self

whose only cure more loss

I am now used to

being carved away.

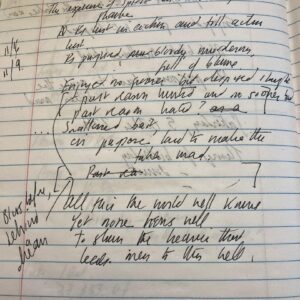

Slow Walk Home’s final section ends with images of finality, of endings. There are nature’s deaths at November’s close (“First Sunday of Advent”). Then “Selfie with Jesus: End times,” where the “end times” are deaths of the speaker’s aunts. And then the book’s final poem, “Last request,” on her father’s death:

In the end, he said,

we are all alone

when I dreaded leaving home. Strange counsel

from my father who believed in heaven. Yet

at his unexpected end, we were all there:

his wife reciting psalms, his son the priest

in prayer, his youngest prodigal, me

dumbstruck like him, silenced by the pump

that filled his lungs with air.

He penciled in unsteady script

on a paper slip

the hardest words of all.

Don’t be afraid.

How appropriate that Suzanne Nussey ends her book with poems about endings.

Peggy Rosenthal has a PhD in English Literature. Her first published book was Words and Values, a close reading of popular language. Since then she has published widely on the spirituality of poetry, in periodicals such as America, The Christian Century, and Image, and in books that can be found here.