First, before even coming

together—how ever many of them there were—before

saying one word, there was a wanting. Yet before

even putting that into words—see how far back

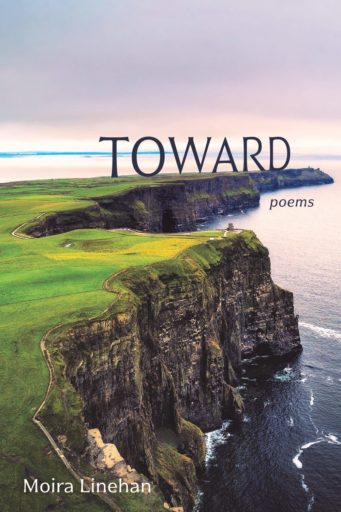

this goes?—there was a need. And that’s what’s driven meto return to these desolate cliffs rising above

an ever-shifting bay.

In these lines from “Spirit Seeking,” the second poem in Moira Linehan’s new collection, Toward, we’re introduced to one of the book’s core themes and settings. The lines refer to Ireland’s first settlers, the Ireland of Linehan’s ancestors, for whom “there was a wanting… there was a need.” It’s the “seeking” of the poem’s title—a seeking which is the motivating force of these poems.

Seeking implies something lacking but needed; it implies a movement toward the need; it implies a longing. We find it ringing changes on “long” in “Widow’s Walks,” which evokes Linehan’s lasting grief over the loss of someone beloved:

all that longing to look beyond, long her refusal to believe he would not return, longer yet her longing for him…

Then there’s the “longing” that takes place (as do many of the poems) in the Irish landscape. In “Let Me Come Back in September,” the speaker walks the wilds of County Monaghan in rainy March, but “long[s] to be walking the lane in September,” “long[s] not to worry how much time I have” before the “rain-fraught clouds” arrive.

In “This Lot,” the longing gets generalized: “How everything on this earth longs to be filled.”

So Linehan uses her rich imagination and craft to fill the earth—at least the earth, the world, of her poems.

Sometimes she fills their world with color. There’s “a yellow bird,/its yellow could not have been more primary,/scarlet markings, as if someone’s fingernails, dipped//in paint.” There’s the tiger lily: “Orange,/but not subdued. Not pumpkin or peach. More aflame.”

But mostly there are grays, splashing their paint throughout the poems—and almost all of these grays are in Ireland: “a bay bathed in perpetual grave gray”; “Connemara skies, perpetual raw gray”; a “blue-gray” mist; rain-filled clouds in “deeper shades of gray”‘; “A thick brush has spread/watery clouds, a gradient of black to rain-/gray.” After all these variants of grays, I had to smile when Linehan writes (in “A Sunday Sky in Rain”) “Who’d have thought an overcast sky/would be so hard to pin down?”

What else does Linehan draw on to fill the world of Toward? Mostly it’s movement. I’ve mentioned the seekings and longings. Related are the “repeated urgings/to find my way to my own/interior… not to run away from what/would carry me where I could/not go on my own, where I/could not even imagine” (from “In This Habitable Desert”).

I can’t let these lines go without mentioning Linehan’s superb craft. These line-breaks leave us hanging just for the instant of wondering what might follow… and what follows is always a surprise.

The book’s most masterfully crafted poem, to my mind, is “This Lot”—an extended meditation on the basic elements of air, earth, fire, water (as “the pond” outside her window), and light. Every line of the poem ends with one of these five words, as in the opening stanza:

And once again the frontier between earth— or at least my backyard slice of it—and fire is about to be closed. Distance closed. Earth lying in wait as I do here at my desk. Earth, bedrock of gravity, its own dome of air, such a happy union, each in its place. Earth, eons of experience: dawn always arrives. Earth, my companion as we both sit by this pond though at the moment darkness still owns the pond. The pond’s just faintly there. I want it to be there. Earth, stately as a heron, now wading toward the first light. Indiscriminate in what it will first bless—light

Then in the last of “This Lot”‘s six stanzas, each of the five lines ends with one of the keywords:

This lot, my destiny. No better source on earth for inspiration, what showed itself as tongues of fire above the Apostles’ heads at Pentecost. Even air, that lover of distance, sidles up to me on this pond, whispers in the wind: It’s coming for you—that light.

In “This Lot,” the speaker is motionless, meditating in place—an exception to Toward‘s central motif of movement. Often (in at least a dozen poems), movement is represented as the speaker “walking”—as in the book’s title poem:

On I walk without being able to say why I must. The language here has been lost, words like woods cut down, hauled off, or abandoned. Yet something remains of those who spoke it. What has always been beyond words, even when they had their own. That’s where I’m headed.

Walking, not knowing why: it’s a form of longing—for language that might come somewhere close to matching the experience of living. Or as Linehan herself puts it in her interview with Slant:

“I most want the reader to see this speaker as grappling with what is so hard to put into words, what is beyond words. Or as Paul Claudel says in the epigraph to my poem ‘Spirit Seeking,’ grappling with the fact that That which each being lacks is infinite. How do you get that into words? Maybe I never will. But I keep trying. I keep moving toward that.”

Peggy Rosenthal has a PhD in English Literature. Her first published book was Words and Values, a close reading of popular language. Since then she has published widely on the spirituality of poetry, in periodicals such as America, The Christian Century, and Image, and in books that can be found here.