The hospice nurse spoke softly. It could be today or tomorrow. Was he the angel of death? The gentle angel of death? He was, after all, the one who met my father when he arrived at the in-patient hospice for his final two days in this world.

In the Talmud, there’s a story about Rav Seorim and the final hours and death of his brother Rabbi Raba. “After you die, show yourself to me in a dream,” Rav Seorim asked. Raba did this, and as soon as he appeared, Rav Seorim asked: ‘Did it hurt?’ Raba said: ‘No; it was like lifting a hair out of a bowl of milk, but were the Holy One to say to me, Go back to the world as you were, I wouldn’t do it. That’s how great a burden the fear of death is.’”

I am not afraid of dying, my father told me about ten years ago. He had recently fallen, cutting his head. While waiting for the EMTs to arrive, he thought that was it. He thought he would die then and there. Were you afraid, I asked him. I was curious. I am a son. I wanted to learn from my father’s experience.

I never asked that question again, not even when he was in his final hours. Was he afraid? Resigned? Indifferent? At peace? Did he even know where he was, where he had been taken after weeks in the hospital?

Unlike my father, I am afraid of dying.

Every year, on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, with other Jews I get to “rehearse for…death,” writes the late Rabbi Alan Lew, “by wearing a shroud and by abstaining from life-affirming activities, like eating and sexuality.”

This year, I abstained. This year, too, as I have for many years, I left my kittel (shroud) in the walk-in closet at home. My kittel is stained. Will the impurities of this world be buried with me? I haven’t worn the kittel in many years because I don’t want to be seen as a hypocrite, a fraud, someone more observant of Jewish laws than I am. Not that I’m not engaged with living a serious Jewish life.

This year especially I have taken the practice of this entire period, from Tisha B’av to Sukkot, seriously. Rabbi Lew’s This is Real and You are Completely Unprepared: the Days of Awe as a Journey of Transformation has been my guide.

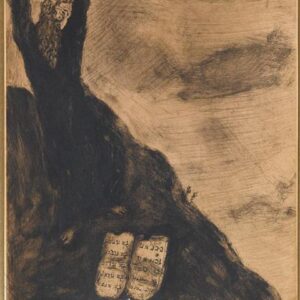

I began, as Rabbi Lew instructs, on Tisha B’av, the 9th day of the Jewish month Av—the day, tradition teaches, on which the First and Second Temples were destroyed. The walls came tumbling down, Rabbi Lew says of those tragic events. What walls—what structures, physical, emotional, psychological, intellectual, spiritual—have come tumbling down in our lives? That’s a question Rabbi Lew asks us to consider.

From Tisha B’av, we move into the month of Elul, during which we read the 27th Psalm every day.

One thing I ask of the LORD,

only that do I seek:

to live in the house of the LORD

all the days of my life,

to gaze upon the beauty of the LORD,

to frequent His temple.

He will shelter me in His pavilion

on an evil day,

grant me the protection of His tent,

raise me high upon a rock.

Now is my head high

over my enemies round about;

I sacrifice in His tent with shouts of joy,

singing and chanting a hymn to the LORD.

Sitting in the ruins of the temple, the losses and failures of a life, all that has collapsed around and within us (the loss of loved ones, the destruction caused by fires and floods, the viral transmission of disinformation and lies, the diminishment of one’s own strengths, physical and cognitive, our own failures to speak truthfully, to act compassionately), we long for protection, security: “to live in the house of the Lord,” “to frequent His temple,” to “shelter” in “His pavilion,” to be protected and to “sacrifice in His tent with shouts of joy.”

After Elul come the Days of Awe, a ten-day period that begins with Rosh Hashanah and ends with Yom Kippur, a time when, according to tradition, God is especially close to us. The sense of God’s nearness may be felt most strongly when we sit with our transgressions without turning away from them. In that seat of our failures, on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, we thank the Creator for life, for exactly this life, and on Yom Kippur, as we “rehearse” our death, we pray to be written and sealed in the Book of Life. After Yom Kippur, joy comes: Sukkot.

On Sukkot, which marks the end of the two-month period of transformation, we build booths, temporary shelters or dwelling places. For eight days, Jews celebrate the fall harvest, eating, drinking, and some even sleeping in the sukkah, the simple booth. The sukkah’s roof, commonly made of bamboo poles, evergreen branches, reeds, or corn stalks, must provide more shade than sun. It is also customary that one must be able to see the stars through the natural roof. The sukkah, like the house, the Temple, and the tent of the psalm, does provide shelter, a shelter that remains open to the world: sunlight, starlight, wind, rain. Of course, even the magnificent Temples in Jerusalem were not impenetrable. The world toppled its walls. Ideas from other cultures—Hellenism, Christianity, others—penetrated the walls of Jewish thought and practice and were absorbed and adapted for Jewish life.

Nothing is fixed, closed, permanent. Our shelters, all of them, from the mansion to the tiny house to the sukkah, and from our ideas about this world and the world to come to our bodies themselves, are impermanent. In the sukkah, we embody this knowledge. Our enjoyment of the food of the fall harvest is intensified by the knowledge that winter is coming. A thought of winter, a mind of winter: indeed, winter, though it is still fall, is already here inside us. We are living, we are dying.

The pumpkin soup I love, pleasantly warm but, in the sukkah, giving away its warmth to the crisp fall air: is that the angel of death? The guests—living and dead (it’s customary to invite influential and beloved Jewish men and women from the past—who join us in the sukkah: are they angels of death?

My father hasn’t come back to me in a dream. So, I can’t ask him how it was, his death. I can’t ask him if, were it possible, he would like to rejoin the living. But I think he’s been teaching me this all along: there is no living without dying. When you’re afraid of dying, you’re afraid of living. I see now: the angel of death and the angel of life—they’re the same angel.

Richard Chess directed the Center for Jewish Studies at UNC Asheville for 30 years. He helps lead UNC Asheville’s contemplative inquiry initiative. He is a board member for the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. He’s published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. You can find him at http://www.richardchess.com