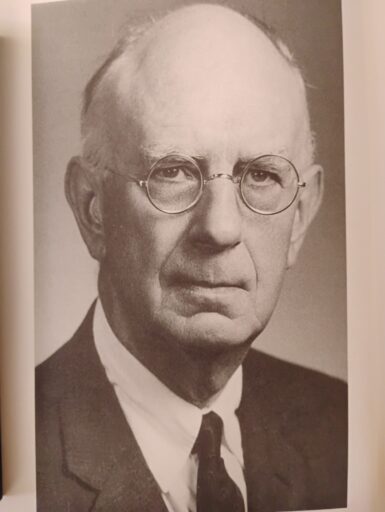

I take a seat as far away as I can, at the back of the classroom and to the side. Yet I still feel vulnerable as the teacher strides in, glowering at us quaking students of English I-II at Amherst College in 1960. Tall, with a bald head, a fringe of white hair, a long face, bushy eyebrows, and round metal rimmed spectacles, he looks as if he will eat us for lunch.

But he’s doesn’t, not quite. And that’s what fascinates me. His intention actually seems benevolent. He’s trying, he says, to help us use words to say not only what we know, but also how we know it. Or perhaps those two activities are or should be the same? I peek at him when he seems to be looking safely away. My expression, as I reimagine this scene, must be one of startled confusion— and then it’s a face frozen in horror as the teacher swings suddenly around to stare right back at me. In fury? No—he makes a face at me, true, a gargoyle-ish grimace, but then returns to class business as if he hadn’t noticed me at all.

At first I am mightily relieved that I have escaped public execution of some kind. But over time I come to think of that brief encounter— the only time we ever connect face-to-face with each other—as a “teaching moment.” He was playing with me, helping me see that the way I was looking at him, as an inexplicable ogre, was a product of my own feverish imagination, and that the only way to free me from my humorless fixation was to shock me out of it. If it was an ogre I insisted on seeing in him, “well”—he seemed to say—“here you go, kid, make what you will of it.”

And in many ways this capacity to unsettle students while at the same time to inspire them was at the heart of the English I-II course that this man had created and shaped over his many years at Amherst, from 1927 to 1969. His name was Theodore Baird.

You’re excused if the name “Theodore Baird” doesn’t ring a bell. But I assure you those whose bells are rung by that name—and rung vigorously—have their own stories to tell of their encounters with Professor Baird over those more than forty years. They wrote, as I did, three short papers weekly in the fall term, two in the spring, all on assignments like this one (from the first assignment my class of 1964 received):

[There is] a distinction between ways of knowing, in which we recognize that some knowing is better than some other kinds of knowing, some knowing is not so good as other kinds of knowing.

If you were to apply this distinction to your own life and say that you “really do know something,” where would you point, what would you talk about?

How would you, dear reader, right now, answer this question? What if you were certain, as we were, that your paper would be commented on (by Baird himself, if you were in his section), returned at the following class meeting and perhaps mimeographed and discussed in class? And if you realized, very quickly, that variations of the questions about “knowing” asked here would persist through the rest of the coming year?

Yet even further, what if you realized, as I am doing now, in my early eighties, that you are just as baffled by those same questions— What do I know? And How do I know it?—as you were sixty years before? Questions no longer asked now by Professor Baird, but by yourself?

My guess is that you’d say, in answer to the last question, that there’s no age limit to our tendency to claim to know more than we actually do. And that goes from claiming to know the world around us to our claiming to know our own minds or the minds of others.

And you’d point out, rightly, that our greatest thinkers and writers have wrestled with our double capacity both to claim knowledge as well as to critique that knowing. And then wrestle with the paradox that the critique itself can be critiqued. Though no writer has, to my imperfect knowledge, won such a match, the wrestling itself is arguably its own reward.

Baird himself did such wrestling in the only essays, just four of them, he published during his career. Three are literary: lively, idiosyncratic critiques not so much of the famous writers focused on—Defoe, Darwin, and Thoreau—but of the ways we usually read them: without sufficient regard for how they are coaxing us to pour more belief into their words than the words themselves can carry (Defoe) or warning us not to do so (Darwin) or doing both, coaxing and warning (Thoreau). As William H. Pritchard (former student of Baird’s and then teacher of English I-II at Amherst) sums up Baird’s intention in Most of It, his compilation of Baird’s essays:

[Baird] set his mind and his formidable powers of mockery against any short-circuiting of the distance between the reader and the imagined world he encounters in his reading—that, with the help of the author, he is engaged in constructing.

One essay, though, goes much further. In “Sympathy: The Broken Mirror,” Baird argues that this short-circuiting of the distance between the words we read and what they mean applies also to how we “read” others, as well as ourselves. To claim to know any Other tempts us to make a leap of the imagination into a world where at best we see darkly.

I’ve often wondered why, given his formidable gifts as a writer of essays, Baird didn’t dedicate his life to that craft. Why instead did he dedicate it to waking the wits of sleepy schoolboys?

My answer is, alas, one of those leaps of the imagination Baird cautioned against. It is, though, a very modest leap. I base it on the other essays (unpublished in his lifetime), fascinating ones, he wrote about the history of English at Amherst from the school’s inception in 1821 as well as about the formation of English I-II in particular. I dare to claim from this evidence that he was a true pedagogue, someone who felt it his duty to provide young minds with the means to deal with paradoxes they’d have to wrestle with their entire lives. It wasn’t easy work, to construct English I-II, then persuade a revolving cast of English teachers (including Robert Frost!) to join your crusade—and keep everyone on task for forty years. And those piles and piles of student papers! I became an English teacher in that mold. Memories of those piles haunt my dreams. But I wouldn’t want to be haunted by anything else. Here and there in those piles, minds are coming alive, looking around in startled confusion, but also in dawning recognition of the joy to be had from wrestling with words and their meanings.

After getting his PhD in English literature, George Dardess taught close reading to his own students until his retirement. Since then he has been ordained a Deacon in the Roman Catholic Church and written several books on Muslim-Christian relations. He has also created the graphic novel Foreign Exchange.