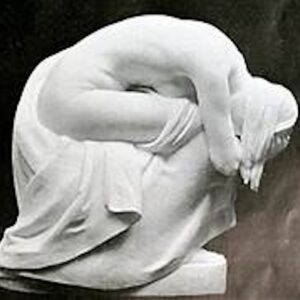

Juturna’s Brave Lament

Juturna’s is one of the bravest laments I’ve ever read in Classical literature. And it’s one I’d never come across until a year or so ago when I decided, after too many years of delay, to read all of Virgil’s Aeneid, from beginning to end, in Latin. Alas, my Latin was and remains very rusty. But rustiness can be an advantage. It’s slowed my reading down, forcing me to dig deeply into each passage and savor it, with the result that details stay in my mind much more firmly.