“We did learn one new thing from your mother this visit,” she said. “You were an accident.”

She didn’t say that!, I snapped back.

“You just don’t want to hear it.”

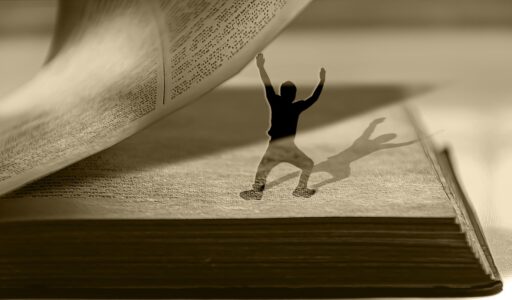

I’m on a page of the book of my life that I don’t want to read.

*

A Jewish Community Center (JCC) in Florida canceled a reading and talk by Rachel Beanland. Beanland’s recently published novel, The House is On Fire, tells the story of the 1811 Richmond Theatre fire in which seventy-two people died. The widely praised work of historical fiction deals with, among other things, the rampant racism and misogyny of the period. According to the Forward, an English-language, digital version of the legendary Yiddish-language newspaper that published its first issue in 1897, after the invitation was extended Beanland received an email message from the JCC asking about the content of her presentation. “This is Florida,” the email said, “and our politics around the Black community, the history of the Civil War, and education in general are complicated.” Beanland replied, according to the Forward, that she would likely “address slavery.” The JCC canceled her talk. After being criticized for doing so, the JCC re-invited Beanland. She declined the second invitation.

Florida flips a page of a book it doesn’t want to read and doesn’t want others to read.

*

Garden

In the first weeks, we already knew

this was history,

that you’d speak of our nakedness,

the flat grasses we wove & slipped over

each other. First there were frills of green

leaf, stalks, tips too. Later came wild

onion, the sharp tang of shoot & bulb.

Then peaches. Standing together in sunlight,

of course, praise & song. We hardly cared

that you would get so much of it wrong,

that you would always speak of an apple or claim

that one of us was so persuaded by the snake.

Darlings, we imagined you. Over & over, how

you would break each other. Wound this garden.

Only then, still licking the dried peach juice

sticky down our fingers, did we know shame.

—Victoria Redel

*

A book reads us. An origin story, an unfinished story still being written corrects our oversimplified, harmful reading of an ancient version of it. It wasn’t an apple. It wasn’t a weak, easily seduced woman. They—those two characters, male and female—imagined us breaking each other, wounding the earth—the planet-size garden on which our existence depends. “Only then,” in response to what they imagined, what they foresaw, “did [they] know shame.”

Torah: a sacred book-in-progress.

*

“[A]n untrue or incomplete narrative of who we are and how we came to be as a country”—that’s what, writes Amir H. Ali, the majority in the Supreme Court presents as justification for recent monumental constitutional decisions: Dobbs and N.Y. State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Bruen. The former, of course, overturned Roe and ruled that abortion is not a right protected by the Constitution. The latter ruled that the Second Amendment protects an individual’s right to carry a loaded handgun in public for the purpose of self-defense. Their rulings, argue the Court’s majority, are based on “history and tradition.” More accurately, writes Ali in “An Appeal to Books,” his Foreword to the recently published book review issue of the Michigan Law Review, “the majority’s understanding of what the nation was like centuries ago.”

Following the decisions, historians, including a joint statement issued by the American Historical Association and the Organization of American Historians, two major professional organizations, criticized the Court for failing to employ “basic standards for historical analysis” and for its distortion of “historical facts toward a particular end.” In its opinion on Dobbs, for instance, the Court stated that until Roe there was “an unbroken tradition of prohibiting abortion on pain of criminal prosecution”. This “unbroken tradition,” the majority argues, “persisted from the earliest days of the common law until 1973.” To the contrary, professional historians find “the strong presence in US ‘history and traditions’ at least from the Revolution to the Civil War of women’s ability to terminate pregnancy before the third to fourth month.”

Lawyers and judges are now bound by the Court’s misrepresentation of history. Additionally, writes Ali, the “next generation of high school civics students will read Supreme Court opinions on major issues of the day and may take the narrative they read for granted.” That’s why Ali makes his appeal to books. “In books,” he writes, “the inaccurate or incomplete story of our nation from courts can be met with a true and full account. Books can be written by people who are experts in their subject and, in the case of history, by trained historians. And, unlike Supreme Court opinions, books about our past can be written in the time needed to adequately verify and contextualize sources, and to account for the complexities of the historical record.”

“I place my hope in books,” Ali concludes, “and their potential to challenge superficial narratives and build a more complete past.”

*

The book of life, the whole book of life, the whole book of my life. Unfinished, uplifting, messy, confusing, disappointing, heroic, tragic, or merely troubling. I mustn’t skim or skip a page. Not if I wish to live with integrity as a man, a husband, a father, a citizen, a son. And not now, especially not now, as I, a Jew, prepare for the Jewish High Holidays, which, as I write this, are less than a week away. As I write this, God, our tradition teaches, is preparing to open the Book of Life and Book of Death. In the Book of Life, God will inscribe the names of those who, thanks to their basic goodness, their willingness to look honestly at the ways they’ve fallen short over the year now ending—breaking another being, wounding the garden—and their renewed commitment to strive to act at all times in a just, righteous, and compassionate manner, will live another year. In the other book, God will inscribe the names of those who, as a result of their wickedness, by fire, by water, by earthquake, by hunger will not survive the year to come.

*

“One good thing came out of that marriage,” my mother said. “You.”

That’s what I heard. Is that what my wife heard? Did those words imply that I was an accident? Is that how my wife heard them? Or did she hear my mother also say that I was an accident? We were eating dinner at a noisy restaurant. Before dinner, I had replaced the batteries in my hearing aids with fresh ones. I don’t want to be asked, did you hear her, did you hear me.

The book of my personal life includes dialogue. But sometimes (too often?) I want to skip a page. A page with something my wife says that I don’t want to hear, don’t want to know.

This year, I’ll place my hope in books—history, poetry, Torah, and that most challenging book of all, the book of my life. Everything is in it—good and bad. I’ll try to catch myself when I’m tempted to skim, skip, cut words, sentences, paragraphs, lines, stanzas, pages, entire chapters that challenge and complicate the simple narrative I’d like my days and nights to tell.

Richard Chess has published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. Professor emeritus from UNC Asheville, where he directed the Center for Jewish Studies for 30 years, Chess serves on the boards of Yetzirah: A Hearth for Jewish Poetry and Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, where he co-directs its Faith in Arts project. You can find him at www.richardchess.com .