Lo yadanu, we do not know, they say to Aaron.

*

“We cannot know,” writes Rainer Maria Rilke.

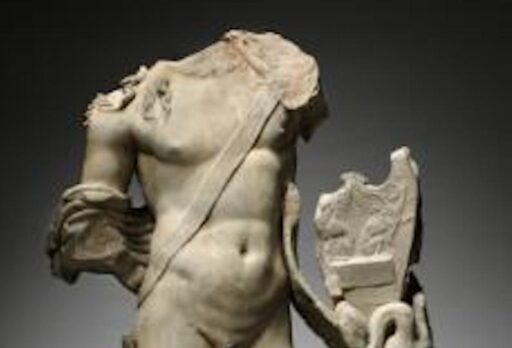

Archaic Torso of Apollo

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

(trans. Stephen Mitchell)

*

Lo yadanu. “We do not know what has happened to him.” Moses, that is. “When the people saw that Moses was so long in coming down from the mountain, the people gathered against Aaron and said to him, ‘Come, make us a god who shall go before us, for that fellow Moses—the man who brought us from the land of Egypt—we do not know what has happened to him’” (Gen 32:1).

*

Lo yodeiah, I do not know. Who’s calling? Who’s texting? Once again, I’ve forgotten to set my phone to “Do Not Disturb” before my morning meditation. The vibration—once for a text, a half-dozen times for a call—unsettles me. My breath quickens, my thoughts race, a host of unnerving emotions flood my system. Should I interrupt my daily practice, my minutes of bringing myself into the presence of God? Maybe it’s nothing, a phishing attempt or spam. Maybe it’s something: my 91-year-old mother, my law-student son…. Not knowing is more troubling than knowing, so I should stop just sitting here, imagining God is here with me, and act—to help if help is needed, to free myself of the discomfort of not knowing.

*

They counted the days. He said he’d return, writes Rashi, our great medieval rabbinic commentator, on the fortieth day before noon. But they miscalculated. Moses ascended early one morning. According to Jewish practice, a new day begins at night. So, the day of his ascent did not count as the first of the forty days. When Moses didn’t return on the day that, according to their calculations, he should have—namely, the sixteenth of the Hebrew month Tammuz—Satan “came and threw the world into confusion, giving it the appearance of darkness, gloom and disorder that people should say: ‘Surely Moses is dead, and that is why confusion has come into the world!’ [Satan] said to them,” teaches Rashi, “‘Yes, Moses is dead, for six hours (noon) has already come and he has not returned.’”

*

Darkness, gloom, disorder. Imagining the worst: the results of a biopsy, the decision of a prospective employer, the landing of a plane a world away. Where a mind, a heart goes in the period of unknowing between a phone’s vibration and picking the phone up. Can you sit in the unknowing without acting? They couldn’t, the people of Israel.

*

When Moses came down from the mountain and saw “the calf and the dancing, he became enraged” (Gen 32:19). The face of an enraged man: a kind of radiance. “He hurled the tablets from his hands and shattered them at the foot of the mountain” (Gen 32:20).

*

Hu yodeiah, he knows. He sees the calf. He sees the dancing. And he knows what can happen to a person, a people facing the unknown. They feel vulnerable. They are afraid. They experience doubt. In such a condition, they are capable of doing anything—almost anything—to escape these most unpleasant feelings. One way out? Create a work of art.

*

“We cannot know his legendary head,” Rilke writes of the “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” but we can know its “curved breast” and shoulders, its hips and thighs. Similarly, we cannot know the tablets, neither the first set, broken, nor the second set, but we can know the story. But can the story, like the statue, know us?

*

I read to be read. To be known: what’s present in me and what’s lacking.

What’s lacking among the Israelites with their calf: faith. Who’s missing: YHVH, the Divine Presence. Moses knows this. Even the tablets know: God isn’t among them. That’s why, says the midrash, the letters fly from the tablets in Moses’s arms. And that’s why Moses, who loves the people even more than the tablets, joins them. That’s why he smashes the tablets. So teaches the Hasidic master Rabbi Yehuda Leib Alter of Ger, known as Sefat Emet (1847-1905). Moses, in Jewish tradition the greatest prophet who ever lived, yes, the man to whom the people said, upon witnessing the thunder and lightning of revelation, “You speak to us…and we will obey; but let not God speak to us, lest we die” Gen 20:16), the man whose face, after returning from God with the second tablets, was “radiant” from the encounter with God, remains, finally, human, fully capable of transgressing just like every one of his people. By smashing the tablets, he becomes inseparable from them.

*

I read to become inseparable from the text.

God’s words, the aseret ha-dvarim, the Ten Commandments, were “incised [Hebrew: charut] on the tablets” (Ex. 32:16). “Freedom”-—freedom from what the rabbis call the evil inclination as well as from the Angel of Death and even death itself—in Hebrew is cherut. The two words, charut and cherut share the same root: ch, r, t. “Only as the light of Torah is engraved and incised on the hearts of Israel,” teaches the Sefat Emet, “are the letters incised on the tablets as well. The real writing is on the heart, of which Scripture says: ‘Write them upon the tablet of your heart’ (Prov. 3:3). That is why,” the Sefat Emet concludes, “the letters flew off when Israel sinned.”

I read closely. But no matter how close I get, there always remains an unbridgeable distance between the text, “suffused with brilliance from inside,” and me. That’s why I read and read and read again.

*

The statue of Apollo. The original tablets.

Broken.

Broken but not discarded, disposed of.

We keep the blank, broken pieces of the first tablets, teaches Rav Yosef in the Talmud, in the Ark along with the second set of tablets. In the Ark: in our hearts.

In our hearts: blank tablet, blank page, blank screen: unspoken, unwritten, unrevealed, unknown. Unsettling. Naturally, you want to turn away from that. Don’t. Turn toward it. Read it and read it again: the unknown. It knows you. Rilke: “there is no place,” not even the Divine Emptiness, “that does not see you.”

Richard Chess has published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. Professor emeritus from UNC Asheville, where he directed the Center for Jewish Studies for 30 years, Chess serves on the boards of Yetzirah: A Hearth for Jewish Poetry and Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, where he co-directs its Faith in Arts project. You can find him at www.richardchess.com.