Longing for home.

“By Babylon’s streams,

there we sat, oh we wept,

when we recalled Zion.

On the poplars there

we hung up our lyres.

For there our captors had asked of us

words of song,

and our plunderers–rejoicing

‘Sing us from Zion’s songs.’

How can we sing a song of the Lord

on foreign soil?

Should I forget you, Jerusalem,

may my right hand wither.

May my tongue cleave to my palate

if I do not recall you,

if I do not set Jerusalem

above my chief joy.”

Psalm 137: 1 – 6 (trans. Robert Alter)

*

Once I lived in Jerusalem. Two years in the late 1970s. I went to the Kotel, the Western Wall, many times to pray. Face of flesh to face of stone, I felt heart. I felt soul. My heart, my soul, my my: too small, too confined to one human body set apart to characterize what I experienced there in prayer.

When I returned to the Kotel for the first time in Spring of 1997, my experience was more political than mystical. The Orthodox control the Wall. They decide who gets to pray there and how. Women leading prayers? Women reading Torah? A girl becoming a bat mitzvah? Women and men praying together? Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, Renewal services? Nope. Not at the main section of the Wall. Off to the side. Out of view. But even there, watch out. A busload of yeshiva, seminary, boys might come in to harass, threaten, even attack a group of Jewish men and women, boys and girls who “violate” Torah as understood by Orthodox and Ultra-Orthodox Jews. Was my presence at the Wall tacit acceptance of a discriminatory arrangement of which I did not approve?

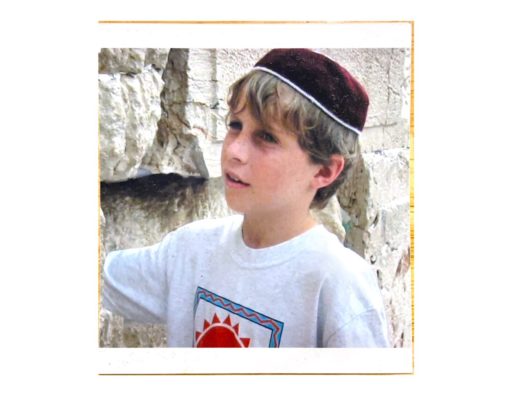

But there I was, now married, with my wife, two teen-aged step-daughters and four-year-old son, standing at a center (the center?) of Jewish religious and historical significance. Could I pray? I remembered Jerusalem—the Jerusalem of my twenties, the Jerusalem of my awakening, of my coming home to Jewishness and Judaism, the Jerusalem of my innocence, ignorance, obliviousness. On the plaza, we scribbled our notes—each of us. My son and I walked down to the spacious men’s section. My wife and step-daughters entered the crowded women’s section. Gabe and I kissed the Wall and wedged our prayers between massive stones. We backed away from the Wall, returned to the plaza, and waited for the ladies. We couldn’t even get close to the Wall, my wife said. Finally, we shouldered our way in and inserted our prayers.

*

Even in Kyoto–

hearing the cuckoo’s cry–

I long for Kyoto.

Basho (trans. Robert Hass)

Even in Jerusalem, hearing Hebrew, the language of Torah and prayer, on Rehov David Hamelech (King David Street) and every street, in Steimatzky Bookshop on Emek Refaim (Valley of Rephaim Street) and every shop, at Doron’s Falafel on Rachel Imenu (Our Mother Rachel Street) and every falafel stand, hearing everyday Hebrew in every kind of mundane exchange—literary, culinary, monetary, social, logistical—I longed for Jerusalem.

*

We longed, even when we forgot what we were longing for. As in Rodger Kamenetz’s “Forget Thee.”

Forget Thee

–after Psalm 137:5

There were cities undreamed of

When we forgot what we were yearning for

In all those long centuries of exile

Cities with names in strange alphabets

That became familiar to the tongue

Cochin, Shanghai, Rio de Janeiro

Crowded cities without tear-stained prayer books

Cities where new dreams scraped the clouds

Cities with palms no psalm ever praised—

Yet I turn back to you with my withered hand

If I were to ask my closest friends, if I were to ask members of Asheville’s Jewish community what they yearned for, what place, what time in their lives, what conditions, few, if any, would say Jerusalem, Jerusalem in the days when the Temple stood, earthly Jerusalem today, heavenly Jerusalem tomorrow. One friend is a fiddler-klezmer, old timey music; another is a woodworker. Not a withered hand in the bunch. But I’m certain that every one of them yearns.

Turning. Turning back to. Turning toward. That’s in the DNA of Jewish life. I’m writing this on the 22nd of the Hebrew month Av, eight days before we enter the month of Elul. Turning back, I see the Ninth of Av, the day the walls fell, First and Second Temples, a day of lamentation, fasting. Turning toward, I see Rosh Hashanah, the celebration of a new year, and Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. Between now and then, thirty days, the month of Elul, a month of introspection and self-reflection, a period during which we acknowledge the ways we’ve missed the mark over the course of the year coming to an end and commit to hitting the mark over the year to come.

“One thing do I ask of the Lord,

it is this that I seek—

that I dwell in the house of the Lord

all the days of my life.”

Psalm 27:4 (trans. Robert Alter)

Beit Adonai, the house of the Lord. Beit, Bayit, the Bayit: the Temple.

Teshuvah, we call it. Redirecting, turning. Heading home.

*

It may be useful to have a place toward which to turn, say Jerusalem, say Eden. Eden, where for a moment we lived in alignment with all that is. That, at least, is how we imagine it, that there was a place and a time when…. If only we could get back…. If we could, I wonder if even in Eden we’d long for Eden.

I long to return to Jerusalem. For a visit. To that complicated, glorious, conflicted, ancient, modern place. To be in Jerusalem as it is now. No Temple. Please, no Temple. To be in Jerusalem as I am now, not as I was in my mid-twenties or my mid-forties or mid-sixties.

Will I pray or at least walk down to the Kotel when I’m back?

“At the Wailing Wall” by Jacqueline Osherow:

I figure I have to come here with my kids,

though I’m always ill at ease in holy places—

the wars, for one thing—and it’s the substanceless

that sets me going: the holy words.

Though I do write a note—my girls’ sound future

(there’s an evil eye out there; you never know)—

and then pick up a broken-backed siddur,

the first of many motions to go through.

Let’s get them over with. I hate this women’s section

almost as much as that one full of men

wrapped in tallises, eyes closed, showing off.

But here I am, reciting the Amida anyway.

Surprising things can happen when you start to pray;

we’ll see if any angels call my bluff.

“Surprising things can happen when you start to pray.” Even where place makes it hard to pray: Babylon, Jerusalem, Cochin. Nonetheless, we pray (“sing”), petition (“my girls’ sound future”), mourn (“we wept”), yearn (“we recalled”), complain (“I hate”), and turn, turn, turn.

And here it is. Home: the turning (longing, yearning) itself toward whatever we imagine is home.

Richard Chess directed the Center for Jewish Studies at UNC Asheville for 30 years. He helps lead UNC Asheville’s contemplative inquiry initiative. He is a board member for the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. He’s published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. You can find him at http://www.richardchess.com