On Idols, Art, Doubt, Broken Tablets, Writing, Reading, Hearts

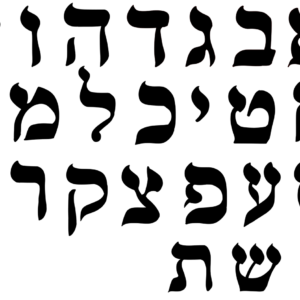

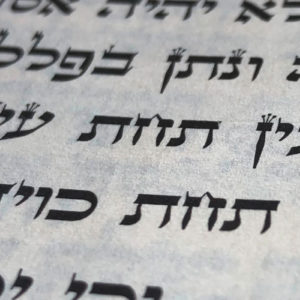

Lo yadanu. “We do not know what has happened to him.” Moses, that is. “When the people saw that Moses was so long in coming down from the mountain, the people gathered against Aaron and said to him, ‘Come, make us a god who shall go before us, for that fellow Moses—the man who brought us from the land of Egypt—we do not know what has happened to him’” (Gen 32:1).