The phrase “Ordinary Time” comes from a season in the liturgical year as practiced by a variety of Christian denominations. Why choose it as the title of your collection? Most people think of the ordinary as boring or mundane.

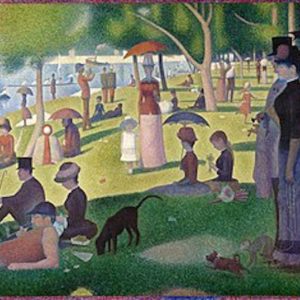

I chose the title for several interlocking reasons. First, because we often don’t see the beauty of what’s right in front of us. There’s the light illuminating the grass, the trees, the flowers as we walk across the lawn, or the light shining on a crowd of people on the city street, each with their own story, most of which we will never know. Only when the dark descends, or illness comes, or absence, or death, do we perhaps realize what we were so freely given but didn’t see or grasp it when we might have.

And, yes, those weeks and weeks of Ordinary Time in the Church’s calendar, which — if we only stopped to look or read our daily missals — are anything but, those days filled with the lives of so many saints, like so many stars, which alas we never stay still long enough to actually see. It happens all the time, doesn’t it? We had the experience, Eliot tells us, but missed the meaning. What poems do, at their best, is help to restore that meaning.

The cover image is striking: a detail of Fra Angelico’s Paradise. Why did you propose that particular painting for the cover?

I remember being awed by Fra Angelico’s paintings there in those monks’ cells in Florence years ago. And then again at the exhibit of his work at the Isabella Stewart Museum a couple of years back, so that I bought a book of his paintings and have pored over his images many many times. But there was something about those beautiful young angels with their upward gaze, a gaze looking past you and beyond, to something they saw that went so far beyond what we call the ordinary. The ring of dancers, beyond the male gaze, their beautiful gaze, what Dante saw as he prepared to leave purgatory and enter paradise. And those trumpets and horns incarnating a music beyond our hearing, yet heard somehow in that mystical silence.

There seem to be a number of interconnected themes in this collection: the relationship between the generations, the role of memory in shaping our identities, the strange dance of grief and grace. Was that intentional or did it just emerge?

One fills the empty canvas stroke by stroke, line by line, most of the time waiting to see where the image or the poem will take us. It’s as much an act of discovery for the artist or musician as it is for the poet. In time the threads begin to connect. In a very real sense I think most poets build on what they have already done, not only in poem after poem, but in book after book, the way Milton and Wordsworth and Whitman and Dickinson did, the way each of the poets I have written about — Williams, Berryman, Lowell, Hart Crane, Hopkins, and Stevens — left behind a body of work which was in many ways their second body, transformed and transfigured, the dark and the light of it all.

And so with this, my eight book of poems composed over the past forty years. Decades ago, I wrote a poem called “The Old Men Are Dying,” a poem about the older generation of my family — my father’s generation and the one before that. And now every one of them has since passed, and it is my generation that is passing. And so I have found myself looking wistfully at my beautiful grandchildren, even as I recall my own growing up on the mean streets of New York City and then the anti-pastoral world of Long Island with my brothers and sisters. And the losses there. Oh yes, the losses. And the blessings. And the faith that has fortified and sustained me through that journey.

There are a variety of poetic forms in this collection. Why such an array of forms?

There are couplets here, and rhymed tercets and quatrains. There are sonnets and a pantoum and internal chimings everywhere. But always I try for an idiomatic way of speaking. I spent many years reading and teaching the poems of William Carlos Williams, with his insistence on the American idiom, and Berryman, with those triple six-line rhyming and unrhyming stanzas that make up his Dream Songs, and Lowell’s blank verse lines, and Hart Crane’s elevated near-mystical stanzas, and Hopkins’s Petrarchan sonnets, curtailed and caudated and some with lines of six or even eight stresses, and Stevens’s multiple variations on the blank verse and four-stress line not to have learned something from them. For me, I want to use whatever works in terms of the emotive and dramatic effect the poem should have to keep the reader’s attention.

How do you settle on a particular form for a poem?

Somehow the poem’s opening lines tell me the direction this poem wants to move. It’s like giving birth to this creature who takes on a life and direction of its own, whether that life lies in a solemn and meditative line, or a jazzed-up, enjambed line that insists on pushing against the underlying stricter metrical music with its own riffs and highlights. That’s the pleasure one finds in singing, even when the subject is a dirge or an elegy for something lost. All of the poets I’ve written about have done this, after all.

How would you say your faith informs these poems?

My faith is central to who I am, no matter the missteps — and they are multiple — that I’ve made on my journey. And a Dantean journey is how I see it. If you’re a Catholic, as I am, then that is going to inform what you write, even when the subject takes place in the so-called ordinariness of time. The truth is that, as I look back, there has always been a light there, even in the darkest of times, and I want to share that light insofar as I am able, by witnessing to it. If there is a Good Friday and a Holy Saturday, there is also — please God — an Easter Sunday. And all of that transforms the ordinary, revealing something extra-ordinary behind and within the day-to-day-to-day.