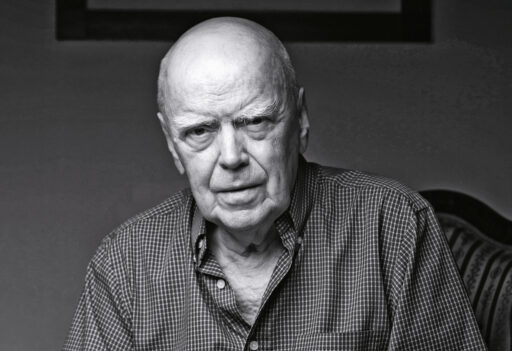

We recently spoke with translator Charles Kraszewski about his new Slant translation of the memoir Kinderszenen, by Polish writer Jarosław Marek Rymkiewicz

Were you familiar with the author or the book when you were matched up to become its translator?

We had what you might call a nodding acquaintance. As a person who is fascinated with both the Polish Baroque and Romantic periods, I have enjoyed Rymkiewicz’s rather quirky critical-historical essays on Adam Mickiewicz (Do Snowia i dalej [To Snow and Further On]) and Samuel Zborowski—though I think I have more of an appreciation for Zborowski’s bête noire Jan Zamoyski than has Rymkiewicz. However, I haven’t had much time to read him for pleasure, due to my obligations as a literary translator. When my daughter-in-law, an avid reader, asks me what I’m reading at the present moment, my answer is always—what I’m working on now! No time for much else.

Were there any unique challenges you faced in translating Rymkiewicz’s literary style into English?

The thing I like most about Rymkiewicz’s writing is his appreciation of form. In poetry, the manner in which he handles the octet throughout all forty four poems of Metempsychoza [Metempsychosis, 2017] is a tour-de force of poetic craft. The very fact of forty-four poems—which number makes it impossible not to think of Mickiewicz—is further evidence of his attention to small, but significant, detail. Some of his creative approaches to form are self-evident, while others are apparent only to the initiate—something that my late friend Jacek Chmielnik finds particularly attractive in writing, as do I.

As far as Rymkiewicz’s prose is concerned, his habit of encouraging readers to “begin reading wherever they want to,” not just at the beginning of a book, requires a much greater outlay of effort on the writer’s part than may appear at first glance. It means that he must construct a narrative that can be consumed and understood in individual portions, wherever the reader chooses to begin—a narrative that can conceivably be read backwards as well as forwards (speaking of chapters, not individual sentences, of course), which makes of the reader something of a co-creator of the book along with the author (Roman Ingarden, and Picasso for that matter, would be proud)…the head fairly spins. Of course, Kinderszenen is not intended to be read in this way, which is something of a blessing.

As far as translating this book is concerned, as always, I am a stickler for form myself and try to approximate the translation to the original as much as possible. As George Steiner says, literary translation should be re-creation. So I am always for retaining those stylistic quirks of the original poet that might even go against the grain of the English reader, such as Rymkiewicz’s long, intricate sentences (whereas English writing favors the pithiness of Hemingway). Outside of that, the goal, of course, is to make the original read as if it were originally written in English, without going overboard and making of a Polish poet a Brit or an American—which would also be a sort of treason. But despite his penchant for long sentences and at times curious punctuation, Rymkiewicz is a clear and engaging writer, so that’s half the battle.

There are several different “angles of approach” the author takes in the sections of the book, from highly “documentary” and fact-oriented to personal recollections of childhood during the war, to discursive essays on various subjects. How does this mixture of approaches work to achieve an overall effect?

Rymkiewicz, like all writers ensconced in a particular history, a particular era, is constantly battling the erosive nature of time. I am always stunned whenever I reflect that the new generation of young people, who are running businesses and even the State in Poland have grown up after the transformation from Communism to a normal, free country. For them, Solidarity, not to mention the December Events of 1970 or something that happened over eighty years ago, like the Warsaw Uprising, is ancient history. So, Rymkiewicz is fighting a battle on two fronts. On the one hand, he resorts to what you call a “documentary” style in order, like a historian, to establish the objective reality of what once happened, while he will switch to “personal recollections of childhood” to make of his account an eyewitness testimony, not merely a thoroughly researched historical account. A well-written historical book documenting the post-Austrian history of Poland following World War One, like Waldemar Łazuga’s Uwiklani w przeszłość [Tangled in the Past] can be a marvelous interpretation of historical realia, but only an eyewitness account by a person who had “been there and done that” carries the tang of immediacy.

It is to Rymkiewicz’s credit that he accomplishes both in Kinderszenen: it is history and testimony. Testimonies are important, especially those that deal with events such as the Warsaw Uprising, or the Battle of Monte Cassino, to offer another example from the Polish experience of World War Two, because such eyewitnesses are slowly, but inexorably, fading from the scene. Which is true of Rymkiewicz as well, who died in 2022. Thank God he was able to leave us Kinderszenen before he passed away. Finally, those discursive essays are never mere digressions. If anything, they underline the real personality of the writer of the book, and all the more confirm his authenticity, inviting us to trust him.

It is said that Kinderszenen stirred up some controversy in Poland when it was published. What did readers find objectionable or debatable about it?

As I said before, at least one generation has grown up since the transformations of 1989, which means that the tangible knowledge “on one’s own skin” of what Communism meant in practice is lacking by many of today’s readers, opinion-makers, scholars, and the ruling elite. Like many countries today (including, of course, the USA), in Poland society is strongly divided between Right and Left. Although I am none too familiar with all of the controversy surrounding Rymkiewicz, there are those in the so-called “liberal” camp in Poland who take him to task for his nationalism, his Russophobia and Germanophobia, as they might say, while there are those “uncompromising souls,” “pure souls” who suffered under Communism who might take him to task for his leftist past, which he rejected during the 1970s, as the Solidarity period dawned.

That he is controversial was brought home to me a few years ago in Kraków. I was sharing a beer with a friend, an old student of mine from my brief days at Jagiellonian University in the early 1990s, now a literary scholar in his own right at the University of Warsaw — here the disciple has very much surpassed his teacher! Anyway, the mere mention of Rymkiewicz aroused a violent—and negative—reaction from my otherwise mild-mannered friend. Of course, Poland and the European Union is a key point of dissension today. There are those who seek a greater integration of the Union as a whole, including Poland, and those who feel that the slightest compromise made in reference to Brussels is an attack on Polish sovereignty. For sure, not many of the former will be thrilled at the way Rymkiewicz equates German leadership in today’s European Union with the hegemony of the Third Reich. Even for me, while an effective literary trope, this is perhaps a bit too much!

Perhaps one of the controversial aspects of the book is its contention that the Warsaw Uprising was both “insane” and completely “necessary.” Do you agree?

As far as Rymkiewicz’s take on this question is concerned, I would let the reader himself or herself ponder his interpretation. The argument that the Uprising was “necessary” in order to underscore Warsaw as the capital of an independent Poland, and not a subject city that would owe its “liberation” to the Russians (who held sway here from 1795 until 1918), is very convincing, and one that—I believe—is confirmed by Miron Białoszewski’s more famous memoirs of the insurrectionary city. As “insane” as it may seem to some, the blame for all the horrors of the battle for insurgent Warsaw is to be lain, not at the feet of the insurgents themselves, but—in the first place—at those of the Germans, who perpetrated great bestialities upon the civilians there, and (perhaps even especially) at those of the Russians—those so-called “allies” (who entered the war, let us not forget, on the side of Hitler) who cynically waited just across the river in Praga until the Germans should suppress the Poles and they should have an even easier time of taming the country after the war, during their occupation (which was to last until 1989).

In short, by allowing the Germans to do their dirty work and eliminate the Polish elite in Warsaw at that time, the Russians, with German aid, were committing a second Katyń Massacre. It is never “insane,” but always “necessary,” to stand up to evil. Of course, there are people today, even some very famous ones, who call the Ukrainian resistance to the Russians “insane.” I believe that they’re wrong—that the Ukrainian resistance is just as “necessary” as was the Warsaw Uprising, and Poland’s initial resistance to both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia in 1939. Knowing myself as I do, I don’t know if I would be strong enough to make such a sacrifice on behalf of the Good, so I will never criticize the Warsaw insurgents—I can only bow my head before them in homage and respect.

In his introduction, Art Grabov says that Rymkiewicz wrote the book as “a warning.” Warning about what? The danger of ulta-nationalism? Or something else?

That would be a question for Art. As for me, I see the book as a warning against appeasing evil, knuckling under to force, which might save one from an outbreak of hostilities today, but really only prolongs the inevitable. Once you give evil an inch, it will take a yard, and much more. Again, Rymkiewicz perhaps exaggerates the danger posed by Germany today—but who knows? Three years ago, did any of us see Putin’s Russia as an existential threat to Europe? Did any of us see a shooting war in Europe occurring ever again? But, the history of Germany cannot be restricted to the anni horribili of 1933–1945, nor can the history of Russia be reduced to Tsarist and Soviet and twenty-first century brutality. Of course, as I say this I start to hesitate. Certainly from the Polish perspective, the history of Russia, from Ivan the Terrible in the sixteenth century until today, certainly seems to be one long current of terror and oppression—both within Russia and abroad. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose…. In Marek Cichocki’s recent book North and South, he skillfully delineates the roots of Polish culture in the Roman, classical, South, which has stamped the Polish spirit with a (sometimes desperate) devotion to Truth and Right, which at times requires great sacrifice. I think that this is what Art is referring to: he’s warning all of us to whom the ideals of Truth and Right and Justice and Fair-play are dear never to compromise on them when evil looms and holds out its scabrous paw in a let’s-make-a-deal gesture. We can never, ever, make a deal with evil.

So, Rymkiewicz’s book is a warning, which teaches us how to act, on the basis of those heroic insurgents, who chose the greatest sacrifice over present comfort. Rymkiewicz is right in suggesting that Poland would not be Poland, then or today, had the insurgents not decided on the Uprising. But this is not a book only for Poles; those ideals which arise from the Roman South are also familiar to Americans and Brits (Winston Churchill, anyone?)—so we should all heed Rymkiewicz’s warning.

How do you think Kinderszenen can help us think about some of the contemporary wars and other violent conflicts of the present time? Though it is a difficult and often bleak book, does it conjure up any hope?

I reckon that I’ve answered this question already. The reason why there were so few Pan-Slavs in nineteenth-century Poland, unlike in other Slavic countries in the West and South of Europe, was that the Poles knew on their own skin what Russian “leadership” meant. The reason why Poland so generously aided Ukraine as soon as the conflict with Russia broke out—and despite the checkered, bloody past shared by Poles and Ukrainians—is that the Poles know what it is like, thanks to the Warsaw Uprising, but not to it alone, to wage a desperate battle against seemingly overwhelming odds, against a seemingly overwhelming evil. It’s hard for any Pole to look upon what has been going on for the past two years in Ukraine and not reflect on what his or her own country has gone through in the past, at the hands of Germans and Russians. But “the truth will be victorious,” as Jan Hus said, on the eve of his great struggle—and this, I believe, is what Rymkiewicz has to say to us through Kinderszenen—and which conjures up hope for the Truth and the Good eventually winning—in Ukraine and beyond.