Paul Mariani’s latest collection of poems, All That Will Be New, just published by Slant Books, covers a wide variety of subjects and poetic forms. There are poems about particular classic paintings, about race relations, about death (including Christ’s), about Covid, about the trees and birds in his own yard, and more. The poetic forms range from free verse to iambic pentameter with ABBA rhyme scheme to terza rima (more on this just below).

For this post I want to focus mainly on the poems about poets—particularly the 117-line tour de force “A Periplum of Poets.” Mariani models this poem on Dante’s Divine Comedy—both in form and content. The form is Dante’s terza rima—a notoriously difficult form, with its interlocking rhymes. The content follows Dante’s journey through the afterlife, with Mariani’s mentor Allen Mandelbaum as his Virgil.

Mariani’s speaker says to Mandelbaum:

And here I am, trapped once again, these decades on

the sands in my own hourglass nearly gone, dear sage,

and this the final journey to learn and lean upon

those poets I spent so many years searching for a reality

in those precious scraps they left, then as now drawn

to their words for what light they might offer me.

“Those poets,” whom Mandelbaum will lead the speaker to, are all ones whom Mariani has written biographies of over the years. Mandelbaum first alludes to William Carlos Williams (“that Jersey doctor”), then Gerard Manley Hopkins (“the inscapes of your Jesuit”). Then John Berryman speaks of his own life and work, followed by “a third shade, the raw- // nerved one who bled out his Quaker Graveyard”—that is, Robert Lowell. Next they come to Hart Crane, and finally to Wallace Stevens, whom we can identify by the fun allusions to his poems “The Idea of Order at Key West,” “The Snow Man” (beginning “One must have a mind of winter”), and “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”:

I heard a voice

grow clearer, as syllables coalesced now into ideas of order.

“A mind of winter,” he sighed, “as if one ever had a choice.

Or thirteen ways of wording a world of multifoliate inflection,

a mundo of gay waltzes where for a moment we rejoice….

The poem ends with William Carlos Williams (“the Doc”) addressing Mariani’s speaker (and concluding in good terza rima form with three rhymed lines):

And now, my time here over, I glimpsed the Doc, the stark

dignity of his entrance after all this time come to tell me what

I’d hoped for. “Yes,” he smiled, “a change will come to mark

the nature of our lines and vivify for those who from the start

sought words rooted in a place and a music to define their art

and leave it etched there on the mind. And, even better, on the heart.”

Following “A Periplum of Poets” are poems honoring specific poets. In “Remembering Phil Levine,” Mariani recalls fondly their times together, like

those long talks when you taught down in New York, living in that

high rise Village apartment with Franny, you reciting “Do Not Go

Gentle into That Good Night,” the whole poem by heart,

in a way that could turn even an agnostic into a believer.

Then “Separated by 2477 miles, I Laugh with Bob Pack Over the Phone,” with its ABBA rhyme scheme and its poignant ending:

“And though we’re bonded here on earth,” you wrote,

we see our laughing selves floating up, beyond all ache,

where we will grieve no more about such loss.” So, let’s take

away from all of this elegiac stuff our laughter, that high note

that will last long after we’re both gone, dear friend, like those

paired trombones you hear reverberating in those purple hills

you have sung so often of, or those loon calls and ebbing trills

of airy laughter as on and on like two rabbis our blessèd banter flows.

Elsewhere in this collection, Mariani alludes, as here, to his advanced age. (Recall from “A Periplum of Poets”: “the sands in my own hourglass nearly gone.”) So he seems to have the sense that this might be his final book of poems. If so, he’s going out spectacularly. And in poems full of surprises. I keep returning, for instance, to a poem that I expected, from its title (“One by One They Fall”), to be about death—but which turns out to celebrate the falling leaves of particular trees on his property. First the poem caresses with its words each specific tree’s leaves—but their fall is not (as we might expect) a premonition of death. Rather—

…think how in time those branches will shake

their way to bud and leaf again come spring.

Call it the silent language of our stalwart trees

that stay rooted here through drought and freez-

ing storms, signing their years with ring on ring.

Why is it that we find ourselves coming back and back

to them? What is it these gentle giants have to say?

Where would we be without them, our world lack-

ing leaves, like words gone silent as they lose their way.

I keep sitting with that closing line…its image that a world without falling leaves would be like a world where words have gone silent.

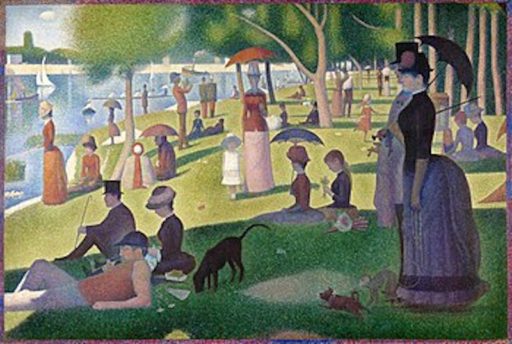

Gone silent. This brings me to the last poem I’ll touch on. It’s one of Mariani’s several ekphrastic poems—this one on Georges Seurat’s famous pointillistic painting “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of Grande Jatte” (1884-1866). First Mariani describes the painting: all those people “floating here, as if frozen / in eternity, coalescing in harmonies of endless dots.” Then he relates the contemporaneous harsh critiques of Seurat’s work. Then comes the final stanza:

Still over and over the painter, who would die at thirty,

kept coming back to his summer’s Sunday afternoon

there on the river as he morphed molecules of paint

into an Eden like nothing anyone had ever seen before.

And here we are, a century on, the question still unresolved.

How shall we read the scene now that everyone we see,

like the creator of it all, has left the stage forever?

It’s an image of disappearance—not unlike that world where words have gone silent. Here Mariani, aware of standing himself with one foot in this life and one in eternity, leaves us with the image of everyone having “left the stage forever.” But it’s not a gloomy image; it’s just…the fact of mortality.

Peggy Rosenthal has a PhD in English Literature. Her first published book was Words and Values, a close reading of popular language. Since then she has published widely on the spirituality of poetry, in periodicals such as America, The Christian Century, and Image, and in books that can be found here.