Contrary to common opinion, close reading didn’t begin in 1938 with Brooks and Warren’s Understanding Poetry. The real date is much earlier and much harder to pin down—though probably Genesis 3:9 marks the start of it, when God looks around for Adam in the Garden. “Where are you?” God asks, though God already knew the answer.

How?

By close reading, very close.

If we ask how close is very close, we get an answer, not from Genesis, but from Qur’an 50:16: “We are closer to him [to each human] than his jugular vein…” (Haleem version). So “very close” is…

Forensically close, like right there at the elbow of your favorite TV crime pathologist in his dissecting room.

Consider these verses from Jeremiah 17:9-10 in the New Jerusalem Bible translation:

9 The heart is more devious than any other thing, perverse too: who can pierce its secrets? 10 I, Yahweh, search to the heart, I probe the loins, to give to each man what his conduct and his actions deserve.

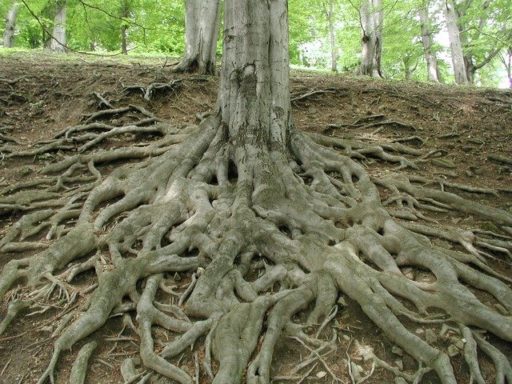

I’ve chosen the Jerusalem Bible translation because it catches the physicality of Jeremiah’s Hebrew a little better than do others. (E.g., the NRSV has “I the Lord test the mind and probe the heart…”). The Hebrew word for “search,” for example, is based on a root meaning “dig,” as into the earth; “probe” on a root meaning “rub,” as when trying metals.

The attention to messy detail pays off. The divine forensic specialist in verse 10 is not confused by the human heart’s perversity in verse 9. No: because the specialist knows how to get to the root of the matter. He digs right in, he gets his hands dirty.

Then there are Hebrew roots that entwine other roots like them, either directly or in sound. The word “devious,” for example, winds up from a root (akov) meaning “heel” or “rear part,” which then branches around the name “Jacob,” who grabbed Esau’s heel. And while scholars assert that the root for “perverse” differs from the one that means “human being,” the two sound nearly the same (like carrots and parsnips if they made an English rhyme, as they can look alike in an English pot).

But God’s thoroughness isn’t merely forensic. God is not approaching a cadaver otherwise unknown. God is picking apart God’s own original handiwork, the creature God “fashioned” (from yazar, fashioning as a pot from clay) “from the dust of the earth” (Genesis 2:7).

Nor is the aim of God’s piercing, digging, probing, etc. simply to poke over dry bones. It’s to find out what those bones have done with themselves since they put on flesh and moved out of the Garden. To God’s eyes, their trail is easy to follow, even when it becomes devious. As Psalm 139 puts it (Jerusalem translation again):

Yahweh, you examine [from the root hakar, dig in the earth] me and know me, you know if I am standing or sitting, you read my thoughts from far away, whether I walk or lie down, you are watching, you know every detail of my conduct…

But God’s reading of us, while rooted in flesh and bone, is not limited to them. Or better said: flesh and bone, in God’s eyes, provide an absolutely reliable witness of our moral health (or lack thereof). No mystery there: God made human flesh and bone that way, as unambiguous representatives of who we are and of what we have made of ourselves.

Poking at Hebrew roots may seem picky. But roots in Semitic languages like Hebrew and Arabic protrude farther above ground than Indo-European word roots do. New meanings more clearly adhere to modifications of that root. As a result, a word’s root truly acts as a root in a Hebrew or Arabic speaker’s mind, powerfully connecting its branchings in diverse forms so that all derived words bear pungent traces of their common origin.

The capacity of Semitic roots to assert themselves in diverse branchings unifies what we, in our dualistic universe, tend to separate: moral and physical connotations. The Hebrew word translated “devious” (akov) in Jeremiah is a good example. Wasn‘t Jacob truly a heel for what he did to Esau? A Hebrew speaker actually gathers in a far richer harvest of connotation than I’ve indicated. Just from akov that speaker gets: the general idea of “rear part”; the specific sense of “heel”; the moral application to hearts somehow misaligned and twisted; and a painful reminder of the dubious behavior of a great ancestor.

Nor is God’s close reading of our bodies confined to this life. It reaches a climax in the next. The Qur’an is especially good at expanding this part of the story. On Judgment Day (according to the Qur’an), God reads us in a variety of ways. One is through the secretarial agency of the two angels who, throughout our lives, sit—one on our right shoulder, the other on the left, both taking absolutely complete, unerring notes on our behavior. The notes on the right unimpeachably record our good deeds. Those on the left, our bad. On Judgment Day, we approach God’s throne, where…

…none of your secrets will remain hidden. Anyone who is given his Record in his right hand will say, ‘Here is my record, read it…’ and so he will have a pleasant life in a lofty garden, with clustered fruit within his reach…(Qur’an 69: 18-24).

But if you’re given your Record in your left hand, well—your fate is like that of the goats in Matthew 25. (See for yourself in Qur’an 69: 25-38.)

Do you think some ambiguity can creep into these Records? Some flim-flam, special pleading, wheedling, lame excuses, melodramatic appeals, passionate denials?

Impossible. Qur’an 36:65 seals the deal:

On that Day We shall seal up their mouths, but their hands will speak to Us, and their feet bear witness to everything they have done.

Once upon a time, for all of us, God’s close reading began, as it did for Adam, by God’s rubbing us between the divine fingers and asking, “Where are you?” But now, in the Qur’an’s picture of Judgment, God isn’t shown reading at all. The results are in. We know where we are, and where, now, we will always be. The roots of the matter lie forever open to the light.

After getting his PhD in English literature, George Dardess taught close reading to his own students until his retirement. Since then he has been ordained a Deacon in the Roman Catholic Church and written several books on Muslim-Christian relations. He has also created the graphic novel Foreign Exchange.