Chardin has always been one of my favorite painters. Now that so many of us are sequestered in our homes because of the coronavirus, his paintings seem particularly appropriate. Why?—because their subject matter is so often the stuff that surrounds us.

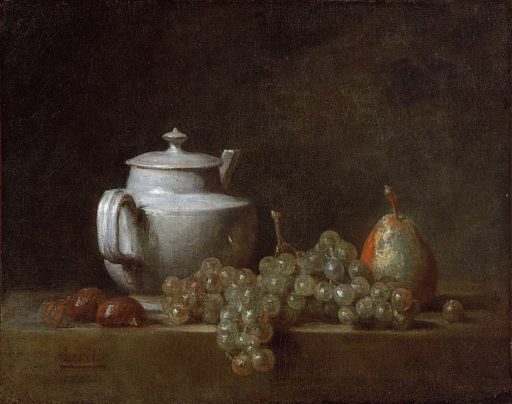

The titles of his paintings are most often unimaginative to an extreme: look at his painting “Still Life with Teapot, Grapes, Chestnuts, and a Pear” and the viewer finds exactly what its title says will be found: a teapot, grapes, chestnuts, and a pear. Look again and again: there is nothing hidden, nothing that you might not have hanging around the kitchen right now.

Yet surely there must be more. Well, yes and no. No, because we must first see them for what they are—a teapot that steeps tea each morning; grapes and a pear that will, at some time during the day, be eaten; chestnuts that will be cracked open sooner or later. And yes, because it’s clear that the painting calls attention to these ordinary things by framing them. Its objects are clearly arranged (both in terms of color and shape) into a carefully planned composition.

Chardin has even added an invitation into his painting—the teapot handle points directly at the viewer and invites us to lift it and pour a cup of tea. And the light makes it seem as if the grapes and pear were simultaneously in the sunlight of a door or window and also glowing with their own internal light.

What makes a household teapot more than a teapot? Why do these pears and grapes—the very perishable stuff of life—seem so timeless? The essayist and novelist Marilynne Robinson might say the objects of the painting exist in “excess” of themselves, as if their very existence were the most astonishing thing that could be imagined. As if Chardin were saying: look at these grapes right now in this light.

In her poem, “Crusoe in England,” Elizabeth Bishop offers the sacredness of use as an answer to my question regarding the teapot. Crusoe had one knife with which to make his “home-made” world. His very existence depended on it. At the poem’s end, when Crusoe is in England, looking back at his life on his “cloud-dump” of an island where the more pity he felt the more he felt at home, he looks at “the knife there on the shelf,” the knife that helped him create shoes, trousers, even a parasol to block the sun. The knife, the shoes, the trousers, the “skinny foul” of the parasol are all to be sent to the local museum. Crusoe asks himself: “How can anyone want such things”? What once gave them meaning was use, was Crusoe’s dependence on them.

Here’s what Bishop’s Crusoe says about the knife; once

it reeked of meaning, like a crucifix. It lived. How many years did I beg it, implore it, not to break? I knew each nick and scratch by heart, the bluish blade, the broken tip, the lines of wood-grain on the handle… Now it won’t look at me at all. The living soul has dribbled away.

What makes a teapot or a knife live? Or more, “reek of meaning?”

If Bishop is being playful and ironic in part when she compares the knife to a crucifix, she is also quite serious—the knife has been part of Crusoe’s daily life, prayed to almost, if only not to break; and the knife lived because it was loved. As Crusoe says, he knew each nick and scratch—the way one knows their own body or the loved body of a spouse.

The knife suffered along with Crusoe (that “broken tip”). And isn’t “use” a matter of love? Crusoe may have had only one knife, but don’t we choose this or that mug over others in the cupboard? Doesn’t it feel like ours, because we know its history (bought in Cornwall, the year our oldest studied abroad). Because we choose it over and over.

And this sandwich plate, turned by a potter on Whidbey Island (her boyfriend makes the best bread on the island), white but rimmed with a thin blue line the color of Puget Sound in the sun—why does every sandwich taste better when I eat from that plate?

And don’t get me started about my favorite pens. They do live. And I do implore them. I know exactly what poem I drafted with this yellow one from Levenger. As Wallace Stevens knew so well, reality is not, say, a chair, but all the life that has been lived in that chair—books that have been read there, and days where I simply looked out the window at birds coming and going from the feeders.

We’re housebound now, and now is the time to take inventory—just look at that stainless-steel tea kettle and how your entire kitchen is mirrored there, waiting for you to take it in.

Robert Cording has published eight collections of poems, the most recent of which are Walking With Ruskin, Only So Far and a new poetry book, Without My Asking. His essay collection, Finding the World’s Fullness, was recently published by Slant. He taught for 38 years at Holy Cross College and now serves as a poetry mentor in the MFA program at Seattle Pacific University.