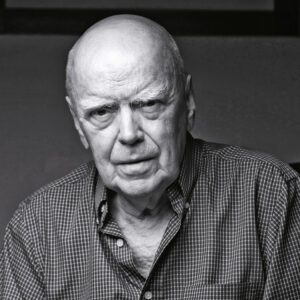

Slant recently talked with Robert Cording, author of Finding the World’s Fullness, about his new book, mystery, and metaphor existing in our everyday lives. Check out the full Q&A below!

The title of your new book is Finding the World’s Fullness. How did you come to this title and what is its significance?

The title of my book comes from a line from a Richard Wilbur poem, “Wedding Toast.” Here’s the poem:

St. John tells how, at Cana’s wedding feast,

The water-pots poured wine in such amount

That by his sober count

There were a hundred gallons at the least.It made no earthly sense, unless to show

How whatsoever love elects to bless

Brims to a sweet excess

That can without depletion overflow.Which is to say that what love sees is true;

That this world’s fullness is not made but found.

Life hungers to abound

And pour its plenty out for such as you.Now, if your loves will lend an ear to mine,

I toast you both, good son and dear new daughter.

May you not lack for water,

And may that water smack of Cana’s wine.

Wilbur’s poem captures my sense that the earthly world can brim to “sweet excess,” that the ordinary and the extraordinary are always tipping into one another. And I agree with Wilbur that there is a “fullness” to be found in the immanent world, though as my title and epigraph from Seamus Heaney suggest, I see that act of finding as continuous—we are always in the act of finding, and what is found is also, in part, concealed. As Heaney says the more we attend to the world the more it grows “distinctly strange”; we become more “focused and drawn in by what bar[s] the way.”

You write: “We live in a time when the language of theological discourse, as Paul Mariani among others have pointed out, has been emptied of much of its former significance.” What can poetry do about that?

I will let Czeslaw Milosz answer that question: “Let reality return to our speech.” This line is from his long poem “Treatise on Theology” in his late book, Second Space. Milosz argues in his “Treatise” for poetry that, while acknowledging the limitations of language, poetry can still strive to evoke the “fullness” that Wilbur’s poem spoke of. What is that fullness, that reality?— to acknowledge the laws of the object, to contemplate, as Milosz puts it, “tree or rock or a man” so that they may bring us “to comprehend that it is, even though it might not have been.”

Your book discusses, among other things, the role metaphor plays in our everyday lives. You draw from your experiences teaching an English course at the College of the Holy Cross called “The Bible and Literature,” rather than the more common offering, “The Bible as Literature.” Tell us a little bit about that distinction and about what you mean by the phrase “metaphors to live in.”

When I contemplated teaching a course on the Bible, I did not want it to be the usual the Bible as Literature. That course often consigns itself to looking at the various biblical genres, character types, tropes, and so on. Its purpose is to reveal the greatness of the Bible as a literary work. Taking my cues from George Steiner and Northrup Frye, I wanted to understand (and to help my students understand) in what ways the Bible’s “demands of answerability” (Steiner’s phrase) are unlike other literary texts. Northrop Frye’s The Great Code and the two books that followed, Words with Power and The Double Vision, all address the complicated problems of “answerability” that the Bible presents to its readers. Although Frye explicitly states that his approach to the Bible is that of a literary critic, and although these works certainly provide a critical apparatus for recognizing relationships between Western literary texts and the Bible, Frye’s task from the outset has been to establish how the Bible is “more” than a work of literature, “whatever more means.” In the course I taught, I wanted to see how the biblical story as a whole, from creation to apocalypse, is a continuing story that asks, cajoles, demands the reader to “wake up,” to undertake the journey of re-finding ourselves (as God asks of Adam and Eve in Genesis, where are you?).

In that sense the biblical stories are “metaphors to live in.”

In the essay “Stanley Kunitz: The Agony of Coming Alive” you observe that, for Kunitz, writing was“an act of gift-giving, the poem a gift he made to the world in acknowledgment of the gift he had been given.” You also say: “I write because in writing I sometimes unite my love and need.” Can you elaborate on that?

What I treasure in Kunitz’s poetry is his abiding gratefulness. He recognizes that we live in a world we did not create, and did nothing to deserve. As I try to sketch throughout the book, that acknowledgment determines the posture of the writer to the world. If imagination is the opposite of fantasy, then it is also an exercise in overcoming one’s self, of extending oneself towards what is different from ourselves. And, in the loving respect for a reality other than oneself, imagination and art call us to attend, with devotion and care, to a world which will always remain a mystery, but a mystery in which love calls us to the things of this world where we may become most fully human. Kunitz lives out these acknowledgments so, so well.

As a writer, I work to shape a language that will take into account a world we did not make, being faithful to that essential mystery; at the same time, my language must try to faithfully record the terrifying and painful contradictions of human experience; and finally it must do so while remaining open to the intrinsic joy of being. My need is to praise. My love for the world keeps me, I hope, both from false praise, and from deforming those painful contradictions of human experience.

You have previously published eight collections of poetry. You generously cite the many influences on your work as a writer. After a lifetime immersed in the craft, what makes writing another poem something new and exciting for you?

In short, mystery. The cover painting of this book has Jacob wrestling with an angel. All readers of the Jacob story are forced to wrestle in order to make some sense out of the mystery of existence, out of the never-able-to-be-seen or understood face of God. Like Jacob, we cannot master our situation, which is always one of partial darkness. We cannot control the people around us, including our own families. In fact, the best we can do is precisely what Jacob does: give up control, wrestle with our darkness, and fight for—at the cost of our maiming—a moment of insight, a poem.