Start with a woman watching a man / Catching his daughter. But find you see with the eyes of the child: yourself, small as a gangly loaf of bread, gripped and flung and caught at the ribs by your father, whose boyish face pumps up and down in the summer yard where he, years ago, once played.

This is the stage on which for a moment you are the only child, the prize, with minor players arrayed in mundane blocking. On the porch, three stand: your girlish mother at the steps, chanting her low catcalls of concern; your father’s father and mother, middle-aged and strong, of one leaning murmur as she sets out dinner, his touch swaying the freckled aspic of her arm.

Note the murmur; turn your flying eye. See the stage-glance from the woman to the mother’s back—the older one’s arched neck, pursed eyes, some sly barb allotted—then swivel and see yourself in flight from their porch view: your own mouth slewed with laughter, / Feet tilted like a landing goose, / and your father’s slender hands / Stretched out in the wind.

End as a woman. In a hotel lobby, before your grandmother’s death, you already wear her wedding diamond. She promised it to you in the garrulous way of the demented, swaying like a tipsy drinker showing off all her opinions: a gift to make good for the wedding ring you lack, to flag the disgrace of your old divorce from a man your grandfather still prefers.

At her side, he laughed a little as she proposed the ring, but you said yes as you would to a child: delighted, unoffended at imaginary gifts—and then surprised, months later, when the ring materialized, real and heavy, deemed safer on your finger than in her nursing home jewelry box. A serpentine band with a thick center stone, it’s not your style but you wear it to dinner tonight, a glimmery wheel beneath the hotel lobby’s staged lights. A friend, a dreamer, leans across the table and slips it from your finger to her palm, holds on and says: “She was a very angry woman.”

Angry? Yes. All the little acts of malice like a scorpion’s tail or the train of a barbed dress flipped at your mother, and then, at last, at you: the former, an interloper by marriage to her firstborn son; the latter, a wife who could not please and was let go.

End with a photo. Your mother will be there, nonetheless, in the hours after your grandmother dies, the only daughter-in-law in the deathbed family portrait. You are absent. Now place yourself in the arc around your grandmother, her arms curved open like a dancer’s on the blanket, her face puffy, somehow childlike. Do you tack to the twins, close at her side, the sisters who make one person of their final worship? Or stand by the doctor, your tall sister who stayed by the bed all night, but stepped out at dawn and missed the giving up of the ghost? Do you pledge yourself to your mother, or to your father, whose second wife is absent?

All this in the final matte pink room, in a nursing home about which your doctor sister quietly said: “No, we shouldn’t.” But we did, for all the reasons why, and from a distance it seems strange to everyone: the final indignation and indignities, the loneliness of an unclean place.

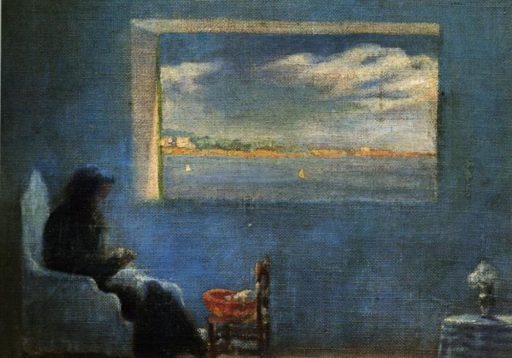

Watch contre-jour, a shadow / In the shade of the capiz-shell lamp, / A mother and the child you were. In those old jostlings, sometimes your grandmother won and was the mother; sometimes your mother won and held the stage. Then the teeth of the curtain wheels cranked and the lights blazed up, and at the final hour, it was the end: the last time your grandmother toddled toward you, all hair and language lost, her blue eyes charged with the surprise of seeing your face.

“She doesn’t know anyone anymore,” your aunt apologized, a summer wind whipping at the nursing home awning, buffeting the waiting car’s open door. You caught your grandmother in your arms: a small, solid body, too heavy to hold on your own.

You have been among the living twice, / And loved both times. / You have fallen in the lurid air. Your father is here and you pass her back and forth, each pivot a slow step, the walker abandoned in the grass. Wedged into the backseat, she sits beside you, takes your hands and knows you: so happy that you have to forgive her, and beg her to forgive you, too—as you will every time you flash your phone open to her childhood portraits, crooked black-and-white stagings in fields, on bluffs, before old farmhouse porches, and make your friends exclaim over her as if she were your own child.

Laura Bramon Hassan is a writer and international development practitioner based in Washington, DC. Her writing has appeared in The Best Creative Non-Fiction, Vol. 3 (W.W. Norton), Image, University of Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal, First Things online, Humanum Review, and other outlets.