My heart sank a little bit.

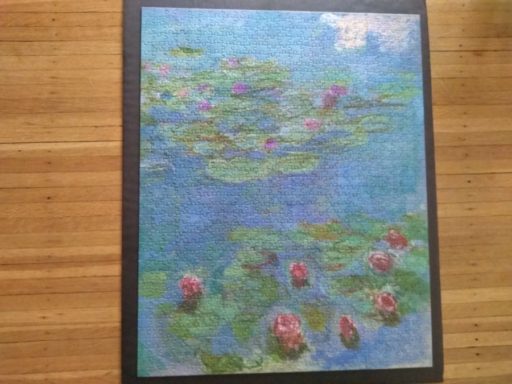

Knowing that my wife Peggy and I love to do one-thousand piece jigsaw puzzles (“good for the aging brain,” we say, in defense of our addiction), our daughter-in-law had just gifted us with Monet’s Water Lilies—the one painted in 1914.

The gift was a gesture of respect, not of challenge. Or maybe respectful challenge. You don’t give Water Lilies to faint-hearted puzzlers. The painting is complex enough. But in addition the reproduction is poor. There are no clear lines and other demarcations to suggest the original’s structural outlines, no unambiguous groupings to be made of pieces corresponding to discreet areas in the fuzzy photo stamped on the box’s lid. Instead you end up—after dumping out the box’s contents and doing some initial sorting—with three blurry puddles of color, one of varied greens, one of varied blues, one of both. Any piece in each looks pretty much like any another. In fact, all the pieces look pretty much like any other. You approach the puzzle knowing that you are seeing what Monet painted through cloudy glass.

But at least the edge pieces announce themselves. We had the puzzle’s frame in place after two 45-minute workdays. (Forty-five minutes, ticked off on a kitchen timer, are our limit. We’ve found that the aging brain can turn to mush or go mad unless restrained by a limit like this.)

But then what? Where to begin?

Well, first, looking more closely at our pieces, we saw there were two smears of color that stood out from the rest: white smudges representing the reflected sun-backed clouds in the upper right-hand corner; and pink smudges of varying shades representing clusters of lily blossoms.

Assembling just those separated areas did wonders for our morale, but then what? What were we to do with the maybe 800 pieces remaining?

And why do anything at all? Why continue with a project demanding, it seemed, nothing more than the mindless trial-and-error of fitting one chip of cardboard into another?

I’m not sure there’s an entirely persuasive answer to my question. No doubt pride and stubbornness played their roles. But we’d never sworn, as puzzlers, to fight on to the bitter end, like gladiators. Peggy and I had quit on puzzles before: on the murky dark green stage floor over which pirouettes Degas’s ballet dancer The Star, for example. But it was hard to quit on Monet’s blues and greens, still iridescent despite the haze of reproduction. Besides, on closer inspection, no piece of green or blue was exactly like another. Many other colors came into play as well. In fact, the closer we looked at each piece—and looking closely at pieces is what puzzling is all about—the more variegated each piece’s color-play was. The more we looked, the more each piece looked like a painting of its own, an Impressionist painting in miniature.

I think this discovery, of the beauty of each individual piece, is the best reason for why we persisted—even when, as in the early days, we ended each session with only a couple pieces put in by each of us.

Were we guided here by how much we’d previously enjoyed piecing together Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grand Jatte? We seemed on that occasion to have become pointillists ourselves, and in two senses: holding in our hands not only the dotted pieces that formed the larger whole of the completed painting, but also the pieces that were themselves the “dots” of the completed puzzle. In both ways, the whole flowed from its parts, gradually absorbing them as it came into full view.

In fact, it was while working on the Seurat puzzle that I began to appreciate what was happening with the piecing together itself. It wasn’t only each piece’s color and markings we were studying. It was each piece’s idiosyncratic configuration: how even with ribbon-cut pieces, the simplest of the three styles of cutting we’re familiar with, each piece is slightly different from another. Lacking other helpful distinguishing clues, we made separate sortings of similarly shaped pieces. And we gradually acquired a mental inventory of remembered oddities. But all of this labor or sorting and matching of color, line, and puzzle shape was at the service of a greater aim, of allowing the individual parts to dissolve into the whole.

I was reminded of this process of dissolution by a comment the great patron of Monet and other Impressionists, Charles Ephrussi, made about their work: that these were all paintings that could “present the living being, in gesture and attitude, moving in the fugitive, ever-changing atmosphere and light; to seize in passing the perpetual mobility of the colour of the air, deliberately ignoring individual shades in order to achieve a luminous unity whose separate elements melt together into an indivisible whole and to strive at a general harmony even by way of discords.”

Monet’s way of working was of course not Seurat’s. But Monet’s passionate search for a method of transforming bits, or tiny strokes, or tiny smears of color into an impression of an impression—the resulting whole registering a moment not frozen in time but instead fluidly passing through it—was an effort we could feel some empathy with through our own fingers as (at times almost without our bidding) they seized a certain hitherto mysteriously isolated puzzle piece and snapped it securely and inevitably into the interlocking arms of the mates to which it had all along been destined.

Some jig-saw puzzlers like to fix their finished work on a glued backing, frame it, and hang it up as a tribute to their own and the painter’s handiwork.

Not us. We prefer to emulate the Tibetan Buddhist monks who came to our city some years ago to construct a large sand mandala at our local art museum. We went several times during the two weeks of their labor to watch them carefully and reverently fill each prescribed area with just the right amount, color, and configuration of sand. When the mandala was finished, prayers were chanted, beginning at the museum, and ending at the side of the river that flows through our city. There, the sand painting was committed to the waves, dissolving into them. The part becoming the whole, and returning again.

Back home, our Water Lilies is now complete. We’ll admire it for a few days, then take it apart and dump it back into its box.

After getting his PhD in English literature, George Dardess taught close reading to his own students until his retirement. Since then he has been ordained a Deacon in the Roman Catholic Church and written several books on Muslim-Christian relations. He has also created the graphic novel Foreign Exchange.