I was told to put clay in the bath, so I do: gray dirt, more like ash or silt, a dust-petticoated lump of it flung from the jar, soft and heavy as it spatters in the tub. I cough at the dust and leave the room to let the tap run and the air warm; I always leave the bath to fill the tub, like I always leave the kitchen to fry bacon—until one of the boys, always the same boy, calls me back just before the oil smokes. I think of him as I close the suite’s bathroom door; I’ll have to remember the water on my own.

Always the same scattered run: papers and bags and shoes I’ve piled around the room, each shucked in a hurry and now collected just as quickly. I could leave them but I want to return to a clean room so I sort and fold and hang things now, losing and finding the book I read in the bath each night, hearing the boys and their father downstairs as they clean up the dinner table.

We found the book on our honeymoon: a collection of poems lodged in an overstuffed old bookshop. I hadn’t read Seamus Heaney in years, but I liked the title—Human Chain—and I bought it in that frivolous overflow of a wedding week: the final hurtling days when money is no object because there are so many gifts to give, and happily. I did not open it until after we returned to the house where my husband’s three youngest sons waited for us, where his first wife and their mother lived and died.

The water is always too hot, the tub slippery with mud. I kneel beside the basin and stir in bursts of cold water, unsettling the slick. When I can stand it, I step in. The honeymoon poems are of waning bodies—beloved, funereal, attended at their sickbeds and their graves: the paralytic lying on his litter, a dead man’s card-party wake, the Narnia wardrobe of a closet that becomes a father’s elderly body: his hanging suits “Like waterweed disturbed” as the child reaches through and finds “Each meagre armpit… One on either side… Having to dab and work / Closer than anybody liked, But having, for all that, To keep working.”

Why did I buy funereal poems in the happiness of our honeymoon? I ask myself this as I dimple the pages with one wet hand, feet hovering at the water. My soles always hold fatigue like trembling drum skins, and I once found that if I set them on the bathwater as if to walk, something in the water’s rubbery edge relieves them. Feet on the water, one pantomimed step and another, I know I am happily exhausted, in a rare way: the last time, ten years ago, in a week of tending a friend’s two little girls. I stood in the sand by the grey-blue ocean and pushed them in the swings for hours, a tedious relief to the tedium of strollers, bottles, and diapers, their happy faces glinting back at me. And at night in our shared room, I watched them sleep and listened to them breathe, and heard and felt my own blood in my happily exhausted head and feet.

But none of this answers the question: why the funereal poems? And why have I read them over and over, lingering with the boy departing the wake, walking the dark field with a foiled, glinting oat grass staff? Why have I longed to comfort the imagined invalid who said he “could bear no longer to watch” the beauty of “The sun going down”? Why have I stood again and again with the man and woman in the grave-like dugout of the calf barn, inhaling earth and nodding at death?

Perhaps because of the man and the boys downstairs, their voices and their steps an unwarranted gift, a place to spend and give myself as I move through my own finite days.

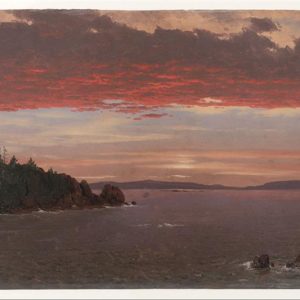

Image: Pierre Bonnard, Nude in the Bath, 1925

Laura Bramon Hassan is a writer and international development practitioner based in Washington, DC. Her writing has appeared in The Best Creative Non-Fiction, Vol. 3 (W.W. Norton), Image, University of Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal, First Things online, Humanum Review, and other outlets.