I read Tagore’s poetry collection Gitanjali in Kolkata on Sudder Street, in a hotel room overlooking an odd patch of land behind two buildings, catching debris that floats and falls down its concrete sieve. Other rooms look onto it, shades drawn, and a bright moon rises in the hazy sky. Does anyone see me standing at the curtains of my room, alone as I read? Does anyone else see the wisps of newsprint lit up as they pass the glow of my room, drifting down like thick, slow flakes of summer snow?

Oh my only friend, my best beloved, the gates are open in my house—do not pass by like a dream. I read these simple poems all in an evening: first lying in bed, woozy with jetlag, and then walking around the room as I try to stay awake. The voice talks to God like the Psalmist, fervent and clear-eyed, but with Solomon’s desire—I tell this to a friend, trying to describe Tagore’s poems, how he seeks God as father, king, lover, friend.

I think of the man who gave the book to me. He strikes me as a boy because of our encounter: him, his sister and me, roaming the city with an innocence rare to adulthood. He brings me a gift each time we meet: a starched red wool-and-silk shawl; a soft handwoven scarf I will wear in cold winters; this book: a picture book with a gold cover and broad pages showing Tagore’s scribbled Hindi manuscripts and each poem’s English translation.

The boy and his sister are friends of a friend, and they find me at my Sudder Street hotel every evening after work. I take them out to dinner: Peter Cat, Scoop, a hole-in-the-wall Chinese restaurant I could never find again. They are orphans—his father gone, her mother passed away—of no relation to each other save affection. I watch their practical way with each other, their teasing and foreknowledge, and they befriend me with a sense of humor that shortens the breach of language and upbringing.

Thou hast made me known to friends whom I knew not. Thou hast given me seats in homes not my own. Thou hast brought the distant near and made a brother of the stranger. I forget to tell them how old I am. Sometimes people assume I am an agemate: ten years younger or ten years older, there’s something in my manner that contracts the time. Sometimes people approach me as a mother: they are looking for something and they think that I can give it. Sometimes I see it coming, and sometimes I don’t.

This happens with the boy and his sister. We are sitting at one of Peter Cat’s famed white-clothed tables, amidst the faded carpets and fatigued Rajasthani-costumed waiters. Families crowd and chatter at nearby tables, everyone is happy. We are talking; we are laughing, too. I say something about friendship, solitude and loving predilection, and suddenly I see them looking at me, a pair arrayed against the black leather banquette.

Their hope is clear. They want to know how to grow up: how to be alone, as I appear to be—older, unmarried, childless, perhaps as unmoored as they are—and yet able to love. With this look, we are no longer friends; we are more and less. I could fail them now.

I read Gitanjali again in a Mount Desert Island cottage on a chilly June day, nursing a summer cold but keeping the window open to the sea air and the sound of the water. I am a mother to another woman’s orphans now, I am a wife to their father. I can hear the children on the lawn and discern their voices one-by-one, unseen but mapped on the green as they play.

Thou hast left death for my companion and I shall crown him with my life. The book is scuffed with travel, the binding split, the dust jacket curled and soft. I’ve saved it from the usual indignity of scrawled notes, but I fold up the page corners of the poems I love the best. I read them again with new eyes: now I know Tagore wrote them after burying his wife, daughter, father, and son, now I see not only the poems seeking God but the poems reckoning with life and death.

I lay the book down on my stomach and listen to the children’s game. Late in this first year of motherhood, they still hide from me, turn their backs or shift their gazes so they do not have to see me. Sometimes they laugh with me and sometimes they approach me as a mother, in the bodily sense: they are hungry, they are tired, and in the daily shadow play of meals and clothes and cleaning, I learn the mannered hiddenness of a servant.

It is the pang of separation that spreads throughout the world and gives birth to shapes innumerable in the infinite sky. The sky is white-blue through the lace of the fir trees’ boughs and I imagine the low, fast-moving clouds scudding above the children’s heads, speeding like a time lapse film. I will never match their mother’s way: that failure always lurking in the old encounters never threatens here, because it is a fact. My presence is proof that she is gone.

It is this sorrow of separation that gazes in silence all night from star to star. I watch the lowest boughs shift in the wind, like great arms sheltering the window by my bed. Quiet is strange in this new life, but solitude is not. What I learned in my old life serves here, a path between the moments when a child turns and assents to affection, the first moments of friendship. I let my eyes close and sleep and wake to read again; the sunlight ripens, gold and warm across the bed, and their voices stay with me.

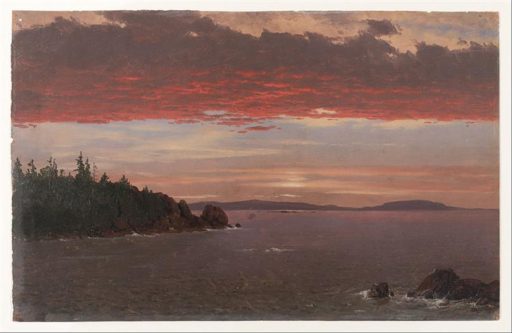

Image: Schoodic Peninsula from Mount Desert at Sunrise, by Frederic Edwin Church (1855). Public domain.

Laura Bramon Hassan is a writer and international development practitioner based in Washington, DC. Her writing has appeared in The Best Creative Non-Fiction, Vol. 3 (W.W. Norton), Image, University of Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal, First Things online, Humanum Review, and other outlets.