Here’s a poem by Yvor Winters (1900-1968), written during World War II, when California was on guard against possible attacks by the Japanese navy and air force. I’d like to lead you through this poem, and share a lesson I learned from reading and thinking about it:

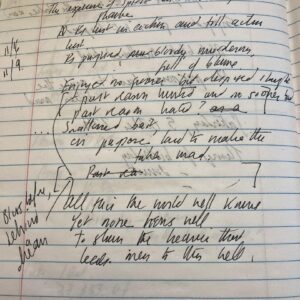

Moonlight Alert (Los Altos, California, June 1943) The sirens, rising, woke me; and the night Lay cold and windless; and the moon was bright, Moonlight from sky to earth, untaught, unclaimed, An icy nightmare of the brute unnamed. This was hallucination. Scarlet flower And yellow fruit hung colorless. That hour No scent lay on the air. The siren scream Took on the fixity of shallow dream. In the dead sweetness I could see the fall, Like petals sifting from a quiet wall, Of yellow soldiers through indifferent air, Falling to die in solitude. With care I held this vision, thinking of young men Whom I had known, and should not see again, Fixed in reality, as I in thought. And I stood waiting, and encountered naught.

Winters taught for many years in the English Department at Stanford University. Los Altos, where he lived, is a small town in the San Francisco Bay area, a few miles from campus. By mid-1943, the U.S. military was advancing in the Pacific against the Japanese. But the outcome of the war was far from settled.

We might assume for a moment that “sirens” alludes to the bewitching singers of Greek mythology who allure and entice men to their deaths. Once we correct this mistake, we might then expect a word or phrase emphasizing the sound that air-raid sirens make. But Winters chooses a word that has a visual implication, as if he were referring to the rising sun or to himself rising from bed.

Sirens do rise in volume, however, starting low and intensifying, and here the speaker reports that they “woke” him. It’s night-time, and it’s “cold,” this word receiving a metrical stress. No other persons are mentioned. Nothing about the room and house where the speaker is. What matters is the sirens, the cold and windless night, and the shift to the illumination amid darkness by a “moonlight” that reaches from sky to earth. No stars, it’s the moon alone that presides over this setting.

It’s hard to know what Winters means by “untaught, unclaimed.” No one has instructed the moon to cast its bright light, nor has anyone laid claim to it, marking it as a possession. It’s far away, luminously distant from, indifferent to, a world at war.

“Icy nightmare” transfigures the coldness of the night. “The brute unnamed” completes the first quatrain, a single sentence. It’s concise, even brusque, evocative but not clear in its reference. Is the speaker conveying an image of himself, saying that this nightmare vision emanates from him? Or are we to imagine that this nameless brute—coarse, insensate, unfeeling, crude, cruel—has an affiliation with the moon?

What has been described so far? In the fifth line, the speaker tells us: it was “hallucination” —five syllables, no “an” or “the” preceding it, and then a period. It’s a perception of objects with no reality; an experience of sensations with no external cause; an unfounded or mistaken impression or notion, a delusion. The speaker’s tone is decisive; this is what it was, though it may intimate his effort to convince himself it was.

Then again, it’s possible that the hallucination is what the speaker depicts next. Winters gives us the image of “scarlet flower,” and, as we turn to the next line, “yellow fruit,” which, as soon as we see it, its color is removed—“colorless.” “Hung” is disquieting, the flower and fruit are without color because everything in this environment is white moonlight and black night.

A period in the middle of the line, and then the noun “scream” to characterize the spine-chilling effect of the sirens on the speaker. The clipped three-syllable “fixity” slows the pace, followed by the release into the rhyming word “dream.” There’s no scent, but there’s sweetness. The word “falling” is made more complex and plaintive through “sifting,” with its sense of petals separating as they descend.

There are no soldiers in this moonlight, but they come alive in death, eerily connected to the color of the fruit: they are alone, isolated, yet—we might surmise—perhaps at peace.

“With care” expresses delicacy, affection, fragility, but the speaker’s response is a determined one, for this is a vision he “held.” He thinks of “young men,” maybe Winters’s former students, dreamlike in a war that he does not identify but that is dramatized by the sirens. These youthful figures: the speaker will not see them again because they have died. But there’s also the implication that he doesn’t want to see them, as if resolved not to (“should not see again”) because of their transformation, the deaths they have fallen into, a sight he couldn’t bear to witness.

The reality for these young men is their deaths. They are fixed to this fate, as the speaker is “fixed,” firmly placed, fastened. He sees them in his nightmare vision, but he’s aware he’s in contact only with images. In truth, while he waited on this moonlit night, no one came, no one was present. The concluding word is “naught,” an old word, from the twelfth century. It means not, nothing, the end.

From its first line, I’ve been led forward by the carefully crafted organization of “Moonlight Alert” and moved by its haunting mood and tone. But it’s not easy to state what it’s about, what Winters is seeking to show us through it. For his part, he would take this as a compliment, for he’s writing poetry, not prose. The meaning is in this arrangement of language, not in any summary or paraphrase through which we might seek to explain it. Even a good close reading cannot wholly communicate what “Moonlight Alert” means.

I bumped into this poem a year or two ago. I can’t remember the book I found it in. I knew that Winters was a poet, but I’d always thought of him as a literary critic, severe and judgmental, idiosyncratic, cranky, principled but narrow-minded. He esteemed George Herbert, Ben Jonson, a few others from the past, and he praised some of his contemporaries, among them his students J.V. Cunningham and Edgar Bowers. He disapproved of, in fact he despised, Wordsworth, Shelley, Whitman, Yeats, Pound, and many others high in the literary canon. I was never inclined to look at his poetry; I assumed it wouldn’t be any good. How could it be, coming from a critic whose judgments and arguments were so outlandishly contrarian?

This is an impulse, a temptation, that’s all too easy for us to submit to: we assume we don’t need to learn about something because—so we say to ourselves—we already know what it is and that we wouldn’t like it. I was fortunate that “Moonlight Alert” caught my attention: the title, the specificity of the place and date, and the “sirens” combined to set off a curiosity I decided to pursue. It prompted me to give Winter’s work as a poet a chance, and I’m glad I did.

William E. Cain is Mary Jewett Gaiser Professor of English at Wellesley College, where he enjoys teaching courses on Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and other American writers. His recent publications include essays on Edith Wharton and Ernest Hemingway.