The Consolation of Memory

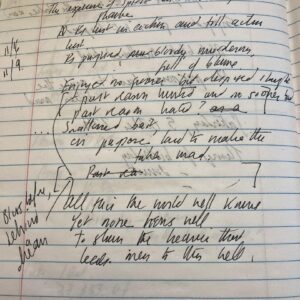

I picked Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129 mostly because, at the time, the sonnet’s edgy tone about the drive to tamp down the earthly passions–—something I was personally dealing with at the time!-—cohered to my own struggles. I scrawled the poem in cursive on notebook paper over and over, trying to memorize it, and in memorizing it, it became a part of me—a part of my body, really