Everything is connected in the end. That’s the sober pronouncement made near the conclusion, on page 826, of Don DeLillo’s 1997 novel Underworld, in which the resolutely anti-modern, paranoid nun Sister Edgar arrives in the afterlife to find herself in an eternal cyberspace, instead of what she’d expected of heaven, alongside J. Edgar Hoover, her philosophical twin. The conclusion manages to be both ominous and incantatory all at once; grim and yet hopeful.

I’ve been thinking about that ending a lot in the last few weeks, as my daughter rounds eighth grade into ninth and I’m reading more and more about the deleterious effects of phone addiction on mental health—particularly Jon Haidt’s After Babel Substack. And one of its most insidious aspects is this polarization of the online world, with its manipulated images and metastasized competition, over and against the solidity of the physical world.

And yet.

Stick with me here, because you’re about to hear a rather convoluted story.

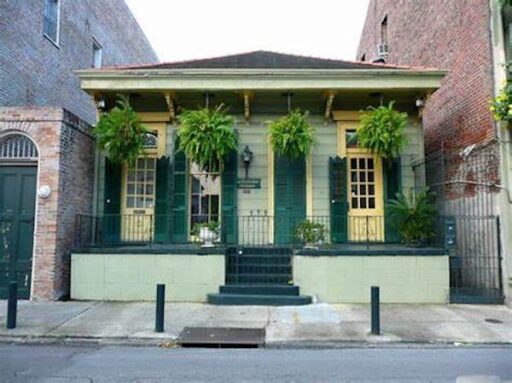

The house was a one-floor Creole cottage, and it hove close to the street like all the other houses in Faubourg Marigny. It had a porch with a balustrade, and tall, floor to ceiling windows that I remember (but cannot confirm) having panes of wavy, ancient glass. Like other people of means who lived in the neighborhood, the couple who owned the house also owned the house right next door, which served as an annex for guests, with the whole complex tucked behind a locked gate.

I didn’t know the owners. I’d taken the streetcar down St. Charles from Uptown, crossed Canal Street, then walked through the Quarter and crossed Esplanade. I was coming because the house guests currently staying in their annex were the parents of the three young boys for whom I had been a Mother’s Helper the summer before. That was in Southwest England, in a thatched-roof seventeenth century house in a tiny village bound about by hedgerows—the wife was English; the husband American, and the English grandmother needed some help wrangling the children so the couple could escape to France for a weekend.

The husband was not only American, he was from Louisiana, too, and just happened to have attended the very university where I was a student. Now it was nearly a year later, and when the family had swept into New Orleans to stay with their friends, they’d thought to call me to come stay with the boys so they could all go out to dinner. And now, here I was.

They all walked off to dinner, and the boys and I played inside the fence until it was time for them to go to bed, over in the annex.

I was left, then, with hours to examine the house and all its abundance. Like most Creole cottages, it looked tiny from the front, but while narrow, the rooms were far bigger than I’d expected, and they were replete with paintings and other artwork—local and European; high art and low—that spanned from the ceilings down to the smooth-worn cypress floorboards. Lengths of rich silk spilled from the tops of windows.

The couple were “older,” but had just recently been married, and looking around their house, I started to put together a vision for what I would want my own domestic life to be like. (And while I have not ended up being a person of means, I am looking at my own silk taffeta curtains as I write this, seated with my laptop at the dining room table.)

I spent a goodly amount of that evening just noticing—for example, the casual and unthinking gesture of how the wife of the couple had discarded her jewelry on the dresser in their room, flung amid small baubles like a bottle of Annick Goutal perfume (it was new then, and from Paris), and a little blue porcelain box, tied up with a porcelain bow, that exactly mimicked a wrapped package from Tiffany’s.

Oh, how I loved that little box, and wanted one for myself. As soon as I had a decent amount of an independent income, I bought myself a bottle of Annick Goutal perfume, but I still don’t have that Tiffany box.

After a few hours, the adults all came home, somebody gave me a ride back Uptown, and I never saw any of them ever again. Decades passed. But after the Internet, pieces of connection slowly began to emerge, a network being traced. And the meaning of these connections has ended up being more than a simple chain of relationships.

Around the time that the emergence of the last president and the subsequent Charlottesville march had prompted new reflection about the insidiousness of white nationalism, the Louisiana-born blogger Rod Dreher posted a reflection on the life of Elizabeth Rickey, the New Orleans lawyer and Republican party member who had first spoken up about the danger of David Duke’s candidacy for Louisiana representative. (Which led to the famous bumper sticker and campaign urging folks to “Vote for the Crook” Edwin Edwards, instead.)

As it happened, the last name of the American-and-English couple was “Rickey,” and only a minute of Internet sleuthing led me to see that this brave woman was, in fact, the sister of the American husband. And though it was by the loosest skein of attachment, like the thread provided to Theseus, there was a connection from her to me. And not just in terms of relationships, but mystically, as a kind of unexpected kinship or inheritance. And which would inform my own action.

Only the Internet could have made this possible, in this way. The connection was intangible, but actual.

I keep going back to that ending of Underworld and trying to decide whether the ending is cynical or hopeful, or whether, somehow, I’ve just fallen prey to being a romantic. In my circles, the drive is ever to push technology away after the necessary work hours, and I’m on board with that; I see the destabilization of focus and the pre-emption of deep and immersive reading as anti-human.

But at the same time, the things touched by the human are also, I believe, touched by the divine. And just as it was only through the chance or Providence of these connections that I was able to incorporate something new to myself, I hold out the promise of the technology and its new worlds incarnating something True and Real, alongside all their destructions.

The virtual world reflects back to the physical one. Just this week, in fact, I decided to search for the name of the couple whose Creole cottage I had visited that Saturday, and stumbled upon the online gallery of the estate sale liquidating its contents. The wife—who I found had lived an epic youth in sixties and seventies Paris before coming back to New Orleans—had passed away. You would assume, as I clicked through the carousel of photographs depicting their belongings, all their antiques and art and bibelot, that I would be thinking of the ephemerality of all that acquisition.

O God no. There, in full color, that whole house opened itself like a book to me again, all in color. The vision in their assemblage did not seem either materialistic or futile, and the paintings flashed one by one on my screen as I scrolled through them.

I was not expecting it at all, on a page near the end of the gallery, when a frame popped up and there, there, in a grove of framed photos, was the little blue Tiffany box, after all this time, returned to me.

Caroline Langston was a regular contributor to Image’s Good Letters blog, and is writing a memoir about the U.S. cultural divide. She has contributed to Sojourners’ God’s Politics blog, and aired several commentaries on NPR’s All Things Considered, in addition to writing book reviews for Image, Books and Culture, and other outlets. She is a native of Yazoo City, Mississippi, and a convert to the Eastern Orthodox Church. She lives outside Washington, D.C., with her husband and two children.