My brother and I lived far away from our parents—my brother, half the country away—so that after our father died (our mother had died before him), his funeral held, the will probated, and the house sold, we had to journey back “home” one more time to gather treasured family objects before the rubbish cleaners came.

Once back there together, we had one frantic day to sift through a hundred years of family history. For that’s how long our family and our grandfather’s family before us had lived in that stately three-story house with its mansard roof.

Don’t worry. I won’t go through an inventory of all the letters, photos, books, and other family memorabilia we frantically sifted through on that final day. I want to focus only on one stuffed manila envelope addressed to my mother that I found among her things. I opened it to find a bundle of at least two hundred drawings done on lined, yellowing school notebook paper with a title page, also on lined paper, carefully lettered in red and green ink. It read as follows:

Designs by Marie Louise Thater from her Inner Life 1969

On the title page’s back, in pencil:

The designs I draw Give me the greatest joy By them is reflected The spiritual light Within M.L.T Nov. 7 1969

I remembered the artist’s name right away. She’d been the art teacher for many years in a one-room schoolhouse in the country village where my mother had grown up. I had met the artist long ago when my mother had taken my brother and me, both still children, to meet her. I recall a tall, kindly woman who had a cleft palate. Her resulting mumbling voice astonished and awed me. My brother— older than I— afterwards used to make fun of it. I’d giggle at that, while our mom shushed me and rebuked him.

Clearly Miss Thater (as my mother used to call her) had entrusted these drawings to my mother’s care. My mother had accepted them, I’m sure graciously, and then put them in a drawer. She never told my brother or me about them, so if she had plans to preserve them beyond just keeping them safe in that drawer in an envelope, we knew nothing of them.

So what was I to do with them now? There were drawers and drawers of my mother’s and father’s own things to look through still, and time was short.

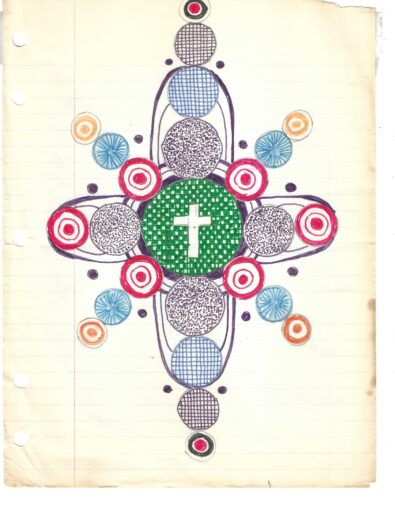

I looked hurriedly through Miss Thater’s Designs. I felt overwhelmed by the sheer number of them. Page after lined page of meticulously plotted circular or ovoid geometric forms of various sizes, all arranged symmetrically around a grounding middle field. The forms were laid out first in pencil, probably freehand, then filled in with color from colored pencils or inked pens. No design was quite like another.

I’ve included above the one design I saved— for yes, dear reader, I kept only this one example and threw out the rest. The reason I saved this particular design is that it was the only one, as I recall, that contained within it a Christian cross. The only one that seemed to suggest to me, at the time, the most important fact about them, Miss Thater’s explicit religious orientation.

But looking at this surviving design now, more than twenty years after I’d first seen it, I see a lot more— not just confirmation of Miss Thater’s religious affiliation, but also confirmation of her spiritual discipline and practice, and of how the two, her love of art and her yearning for enlightenment, combined and enhanced each other. And not only that: how that enhancement could become a benefit and blessing for those who might study these designs. As the artist herself says, “These designs I draw/give me the greatest joy/By them is reflected/the spiritual light.” Note her use of “the.” Not “a” spiritual light, and not “my” spiritual light, but that light itself, as it manifests within all of us. Miss Thater knew exactly what she was doing when she drew the designs and what she was doing when she entrusted them to my mother. She wanted them to be passed on for the benefit of other seekers of the “spiritual light/Within.”

Looking at this lone surviving design now, and recalling the many others like it that I discarded, I see immediately their likeness to other artworks, especially Buddhist mandalas (“mandala” comes from the Sanskrit “circle”). But like Buddhist mandalas— or even Christian icons— Miss Thater’s “designs” aren’t exactly artworks. Or they are artworks and something more, something better. They are aids to meditation, material means to focus our attention away from the flux of time and incident to the goal of rest and a shared unity beyond.

Well, if they’re as valuable as all that, why did I throw almost all of them away?

Panic explains most of it. I just couldn’t see how I could add this bit of burden to the piles of letters and other memorabilia I was already collecting. My brother, I could see, was dealing with his own piles. We’d already been talking about what among our mom’s and dad’s things we’d have to throw away. None of the inhabitants of this house, including ourselves, had been able to throw out anything whatever— or so it seemed to us.

A rather “hip” esthetic judgment explains the rest: my assessment that Miss Thater’s art just didn’t measure up. The materials and the techniques weren’t polished, weren’t professional. Cheap, lined schoolbook paper, ordinary pencils, pens— basic, even childish tools. Naïve, static designs. No attempt to convey ambiguity, paradox, alienation, struggle, torment. No satiric thrust, no overturning of convention. Just a steady, calm, unwavering effort to delight the viewer as well as the artist herself and to strengthen both of them in the discipline to look beyond the darkness of mortal life with its cleft palates and other sorrows to the light within and beyond.

So out those “extra” designs went.

And they’d probably go out again if I were faced today with the same panicky situation.

That’s a hard admission for me to make. My consolation, such as it is, comes from the age-old truth that eventually, everything, all our artistic works, however crude or polished, whether focused spiritually or not, must be left behind. If a remnant is saved, it must stand for the whole, to inspire a likeminded dedication to the joy of creation and to the creator’s only lasting reward, a glimpse of the inner light.

Tibetan Buddhist sand-painters have long embraced this truth. A group of their monks came to our city some years ago to create in the city museum one of their sand mandalas. My wife Peggy and I went daily to watch their meticulous pouring of colored sand in just the right places. When finished, the monks took the mandala to our city’s river and scraped the design away into the current.

They left nothing behind except the inspiration to create it again.

After getting his PhD in English literature, George Dardess taught close reading to his own students until his retirement. Since then he has been ordained a Deacon in the Roman Catholic Church and written several books on Muslim-Christian relations. He has also created the graphic novel Foreign Exchange.