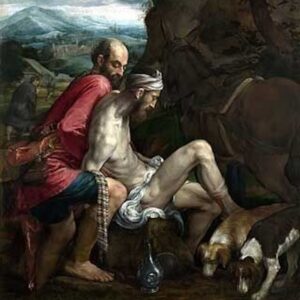

Hemingway and the Good Samaritan

Ernest Hemingway said he wrote on “the principle of the iceberg”—1/8th above the surface, 7/8th below. For him, less is more, the meanings more powerful because they’re not stated, but implied. That’s why Hemingway has been praised for his art of omission, knowing what to leave out. It’s why the novelist Anthony Burgess honored him for teaching writers “how to use the silences between words.”