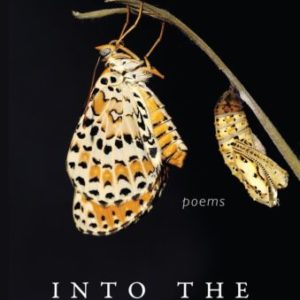

Adam Zagajewski, Poet of Possibility, R.I.P.

Rereading Zagajewski’s poems now, I’m struck by a particular vision often running through them. Of course, any poet who published fifteen collections over forty-seven years will have engaged a variety of themes, moods, moments. But in my current reading of Zagajewski, what’s standing out for me is what I’ll call his “poems of possibility.”