We recently spoke with author Nance Van Winckel about her new Slant book, Sister Zero.

You’ve published five collections of fiction and nine books of poems, but this is your first book of nonfiction. Could you talk a little about how you found your way to this book?

During the years I was writing the pages of Sister Zero, I was also teaching myself to do mosaic tiling. With each little project—covering a wooden box, a mirror frame, a clay pot—I learned from small successes and big mistakes. (Plus, smashing china plates can be very cathartic!) Eventually I attempted covering the top of a large round table. With mosaics, I found the pieces look best when different colors and shapes abut each other.

I worked on this book in much the same manner: focusing on one piece of memory at a time. When I felt I had a piece right, its shape and edges honed, I’d set it aside and move on to writing another piece. And another. This went on for over a decade. Just chiseling the pieces. I took months-long breaks. Otherwise, I suspect the sadness of recalling these events would probably have pulled me into a deep well of despair.

When I finally began to set the pieces next to each other, trying them out in many different arrangements, thinking about how they might best spark and nestle amongst each other, gradually the larger mural came into focus. Also, during that decade I’d been reading other authors who worked in a similar manner with their own hard stories: Maggie Nelson’s Bluets and Judith Kitchen’s Half in Shade, as just a couple examples. Both of those also had a kind of hybridity to the language itself: prose that often drifted into poetry or vice versa.

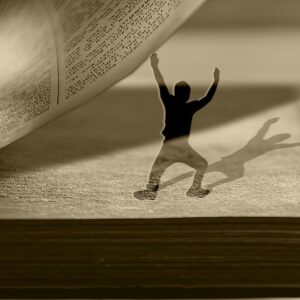

I decided in one of the last pieces I wrote to acknowledge this mosaic M.O. of mine: “In France an old man built a whole house this way, then went and lived inside it.” I still do this kind of work, and I can see how such an enterprise could evolve into a dwelling place. (His name was Raymond Edouard Isidore; this photo shows his work, called pique assiette, on his cottage.)

A more conventional narrative might have played a little more directly to the deep emotional aspects of your experience, but you’ve chosen a form that creates a little distance between reader and emotion. It’s a risky move but perhaps it actually gives the reader more of a chance to feel those emotions for herself?

Good question, and at one point I did complete a chronological draft. I wasn’t happy with that version, though. Conveying the events along a straightforward time continuum seemed to imply a causality between events that didn’t seem accurate.

Moreover, if I started the book with a chapter about our childhoods, that’d just be boring. Our childhoods, aside from the umpteen moves around the country, were quite average, and relatively happy.

However, keeping the time continuum clear for the reader was a real concern for me, and I tried to give a sense of family members’ ages and eras as I reworked and revised.

As my mother’s Alzheimer’s worsened and she began to live in an assisted living facility, she would ask me to tell her about our family, specifically where each husband was, what had happened to them, and to my sister. She liked detail. I gave her details, but I often skipped the sad parts, which only seemed to make me remember those parts more keenly. From my mother’s listening and questions, though, I felt the truth about memory, what a mishmash it may become in our minds as people blur together, events get bollixed up, and what happened to whom feels uncertain. I would tell my mother an upbeat story about her grandson and then go home and write down the real version, the tough facts.

I appreciate what you say about the reader constructing the emotion or what I like to call the emotional layering. That our family had had a few relatively peaceful happy years perhaps left us all quite unprepared for, and often overwhelmed by, the illness, alcoholism, suicide, imprisonment, and dementia that entered our little world. Not that anyone is probably ever quite prepared for those things, but I suppose we kept believing that eventually we’d all get back on an even keel again. No one suspected that the dark times would get ever darker, that the even keel was wonky and full of holes.

You start each chapter with a collage you made from The Official Guide to the 1964 New York World’s Fair and end each chapter with some bits of advice from Mr. Ed of the TV show. Could you share your thoughts on how those pieces serve to frame the chapters?

I was making these World’s Fair collages during that same decade of writing the pages of Sister Zero. The 1964 New York World’s Fair had been a vacation trip for our family, a time when all seemed right with us. The World’s Fair showed me up close and personal how huge the world was/is. This knowledge hit me hard. I was twelve. I suddenly realized how different other cultures and countries were from the many small-town American suburbs I’d known. I remember talking about this with my family. It was a time too that I felt protective of my sister, a role that I had no idea then that I’d continue to play for the rest of our years together.

Working with that old guidebook to the Fair and its touting of a bright and exciting future, I realized I was bringing my later-life, twenty-first century response to the myth of the glorious future, a response I sensed also included a more complicated version of the happy American family.

Mister Ed came late to this book. Working on these pieces, beginning to arrange them, I sensed that the book was just too freaking sad. The whole thing needed some more cheerful counterpointing. One day when I accidentally heard the TV show’s theme song, Mr. Ed returned to me, full force. Watching that show with my younger sister had given us small upbeat moments. We had the living room to ourselves. She was often unsure what wisdom Ed was imparting, which made me a little unsure too: adult troubles. Who knew? So I watched these TV shows again as an adult. The preposterousness of it all made me smile.

Years ago I’d written a series of poems about Jonah and the whale, poems that also seemed to reflect on grief, being in the belly of it. Those poems had never seemed to fit in any of my poetry collections, but when I decided to let Mr. Ed utter passages from those poems, I sensed I’d hit upon a satisfying way to give poor old Ed a little gravity.

Using a collage to begin each chapter and advice from Mr. Ed to end each one, I found a sort of design or shaping around those mosaic pieces. Borders. Grout lines. This, I hoped, gave a stronger shape and design to the whole swirl of pieces, to our lives and what we’d gone through together and alone. Like Isidore, I’d made something from the shards and brokenness.