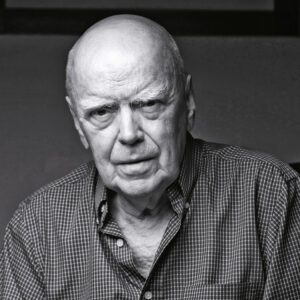

We recently spoke with John Touhey, who contributed a substantial biographical essay about the author to the just-published Slant title, Cry of the Heart: On the Meaning of Suffering, by the late Monsignor Lorenzo Albacete.

You wrote an extensive biographical essay on Monsignor Lorenzo Albacete for this volume. Though you knew him well, did you find anything that surprised you or caught your attention while researching it?

I have been gathering and archiving Lorenzo Albacete’s writings and related audiovisual materials for the past five years. As a result, I now have a fairly comprehensive knowledge of Albacete’s overall body of work, but writing the biographical essay was an opportunity to make connections between all these materials and discover the person behind them.

While preparing the biography, I realized that there was a deep connection between Albacete’s theological concerns and his own experiences, particularly with his family and his ministry. That is especially true of the talks that form the basis of Cry of the Heart. It is a book about suffering and approaches the topic through the lenses of theology and literature, but the questions he asks are really burning questions that are tied to his own shared experiences of suffering through the illnesses of his mother and brother. During this period, his mother was confined to a nursing home and was near the end of her ten-year battle with Alzheimer’s. Concurrently, Albacete was caring for his brother, Manuel, who from a young age had exhibited signs of schizophrenia. Albacete kept a diary at this time and some of the entries are very difficult to read even now, thirty years later.

Many people think of Lorenzo Albacete as an exuberant, funny, larger-than-life figure (and he was!), but there was also another side to him which readers of the book will hopefully discover.

What do you find most compelling about his meditations on suffering?

It is the breadth of Albacete’s vision that most moves me. He had a very active, inquiring mind. The questions he put to existence never ceased, right up until his last breath. And he was willing to look for answers everywhere—so in this book he draws upon the experiences of Elie Weisel, the writings of Walker Percy, Flannery O’Connor, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, the theology of John Paul II, along with the experiences of children and saints….

Somehow he seamlessly weaves all these examples together and invites you to look at your own experience of suffering and start to take the same journey he has been on. I also found his thoughts on co-suffering very helpful. My own suffering is one thing, but how do I face the suffering of my spouse, my children, my neighbor? With sympathy? Tenderness? Albacete shows how without an openness to Mystery, even the most enlightened position in front of suffering will ultimately lead to negation and violence.

The origin of this book was a series of talks to a healthcare community. How might this book influence that community today?

This is something I am very eager to see for myself! Does the question of the meaning of suffering even come up in the healthcare community these days? Medical care has become so technical and numbers-driven that many doctors seem unable to see the person inside the patient. Two years ago I had a friend who had a very advanced case of esophageal cancer. He entered one of the best medical centers in the US and was taken under care by a respected oncologist, who took a very active interest in his case and convinced him to undergo an experimental treatment. The doctor visited him on a regular basis—until the day it was clear that the treatment was ineffective; then the doctor never showed up again to see my friend.

The realization that he could not be cured was an intense source of suffering for my friend, but I could tell that it was just as painful for him to accept that the doctor did not have the least interest in him as a person and was unwilling to share or at least acknowledge his suffering. In such a situation you feel like a lab rat, not a person. As Albacete points out, suffering is not just physical or mental, it is a spiritual malady. A healthcare system that does not recognize this is ultimately inhuman.

In fact, Albacete’s motivation for writing down these thoughts was precisely the inhumanity he perceived when his mother was first treated in a hospital in Boston—a Catholic hospital, no less! He understood that even Catholic-based medical systems had lost their sense of purpose, hence this book—which is a “cry” for a different way of facing the sick and suffering. As Albacete makes clear, we are coming to a stark moment in human history where we must either accept suffering as an experience that is meaningful and has value, or we will all go the way of Canada and decide that suffering is something that is best eliminated, even when it means eliminating the person, too. So, I hope many medical professionals pick up this book and engage with the questions it raises.

What do you think his writing—and the human temperament that so clearly inhabits it—can bring to the religious, intellectual, and professional communities today?

We need to be fearless as Albacete was fearless. He was not afraid to ask any question—not even to question God himself. Nor did he hesitate to engage with anyone. This kind of openness is very freeing. It enables faith to become a life, because when all the barriers we put up between our spiritual lives and our worldly existence are broken through, that is when life really becomes interesting.

Most of us lead very segmented existences, and for Christians this can be very painful because we have a sense that this shouldn’t be so. You can’t be one person with your family, another in Church, another at work—it is unsustainable and dries you up inside. For Lorenzo Albacete this division was intolerable. A lot of his humor and his boisterousness, in fact, came from this refusal to accept this segmentation of everything.

Before he became a priest, Albacete was trained as a scientist. He understood that science, medicine, religion, politics, etc., each had their own methods of searching for truth and these he respected. But scientists, doctors, priests, politicians, sanitation workers, and the woman lying in a nursing home bed are first of all people. We all want to be treated with dignity, to have friends who are honest with us, to be free to look for happiness. Maybe these desires are completely irrational, but we have them. The person who understands this is open and eager to look everywhere for others who share these desires—be it in art, in science, religion, philosophy, even a reality TV show—if there is something there that can help me in this human journey, then show it to me! For Albacete this was not an attitude or a platitude, it was the way he really lived, and it is evident in every page he ever wrote. I believe this is what makes him such a compelling figure to many people still.

You are part of an organization called the Albacete Forum. Could you explain your mission and activities?

Lorenzo Albacete was a brilliant, marvelous human being. He was also one of the most disorganized people I ever met. Partly this was due to his unusual family circumstances, which folks can read about in my essay in Cry of the Heart. But messiness was also part of his character. A few years after Albacete’s death, Olivetta Danese, who had labored valiantly for more almost twenty years to handle this aspect of Lorenzo Albacete’s life, approached me to ask for help in organizing his papers. There were boxes and boxes of materials—and I quickly realized that there was a great deal of uncollected materials scattered who knows where. There was a real danger that all of Lorenzo Albacete’s unpublished writings would be lost and that his memory would soon fade away.

That would be a cultural tragedy. In response, a small group of his friends formed a nonprofit in order to gather and archive his writings and talks, to preserve and promote his legacy, and ultimately to publish his writings. That is where Slant Books was a godsend. Lorenzo Albacete only managed to publish one book in his lifetime. Cry of the Heart is now our second book with Slant, the first being The Relevance of the Stars. We could not be happier with the partnership. Slant has done a marvelous job in editing and releasing these books. They are labors of love for all of us. For me, the work of the Forum is an act of friendship, not just to my friend Lorenzo, but to all the people out there who can now encounter him in his books and the other materials we have on our website and YouTube channel. Reading and listening to Lorenzo Albacete, they will find not just an author or a funny theologian, but a true friend.

Leave us with one anecdote about Monsignor. Your choice!

This story comes from his brother, Manuel, who sadly died last year. Apparently Manuel and Lorenzo were driving somewhere in Puerto Rico when they got into a fender bender with another car. The driver of the other car got out and started apologizing profusely. He was clearly very upset and nervous in a way that was excessive for such a minor accident. This man begged Albacete not to report the accident. There was a young woman in the other car and as it turned out, this man was having an affair with her and didn’t want his wife to find out. It was like a scene from a bad movie! (I don’t think there could ever be an Albacete movie—most of the plot twists would seem too implausible.)

Anyway, Albacete calmed the man down and assured him that he did not want to cause a scandal. Then, without any hint of moral condemnation, Albacete began to ask him about the situation, about the girl, his wife—basically, he was fulfilling his duty as a Catholic priest, but in the gentlest and most human way possible. He encouraged the man to consider the situation from the perspective of the girl and his wife. By the end of their little conversation, the man had decided that he still loved his wife and needed to break things off with this young woman who he only cared about in a selfish way. Who knows what happened after that, but for a moment this stupid accident became a possibility for something more for that man no matter what he eventually did.

There are many funny Albacete stories, but this particular one has stuck with me, because it reveals how he saw his vocation. He truly wanted to befriend others and to help them in a true way. And he is still doing that.

John Touhey is a writer and filmmaker. In 2017, he co-founded the Albacete Forum along with other friends of Lorenzo Albacete.