We recently spoke with author Paul Mariani about his new Slant book, All That Will Be New

This is your ninth collection of poems—since your first appeared in the 1970s, they have now spread out over five decades. What can you tell us about writing from that perspective in time?

No matter how many poems you write, the challenge is always with the blank page as you begin to write your next poem. There’s the emptiness, but it’s like a mirror with so many ghosts and echoes on the other side. Where are you going? Do you really know where this particular poem will lead you? Sometimes you do have an idea, a jumble of energized music swimming around as you look into what appears to be a void.

I often think of the opening of Genesis, with the Creator shaping a universe out of nothing. Then streams of molecular light bounding about, then the forms beginning to take shape, but only as word connects to word and line to line. And always, the effort to make it new, to move on to the next step in the journey.

As with music, there are so many forms, so many ways to flesh out the line, or break the line with silences that give us pause and help us to reassemble our thoughts. Each of the poets I’ve written about has helped me with rethinking the craft. There’s Hopkins’s return to the roots of the English language and by extension that sprung rhythm which helped us rethink the quantitative verse line—the iamb, trochee, anapest, dactyl, and even the spondee.

Then there’s William Carlos Williams’s so-called free verse—the poet who reminded us that there was no such thing in real poetry as free verse, which can too easily slip into prose. There’s that internal chiming, those surprising line breaks, where a red wheel becomes a red wheelbarrow, and glazed with rain morphs into rainwater, and white—that Melvillian abstraction—settles into white chickens. There’s the brilliance and zaniness of Berryman’s reconfigured Shakespearean sonnets into those three-stanza jazz-infused Dream Songs. There’s Lowell shifting from Allen Tate and the Southern Fugitives to Williams, as well as what he called his imitations of Baudelaire and the ancient classics. And on and on: Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, Emily Dickinson. I’ve tried them all—free verse, the ballad, the sestina, the villanelle, the sonnet, even long patches of terza rima, here in my current collection—in homage to Dante and my former mentor, Allen Mandelbaum, who taught me so much with his translations of Dante, Homer, Ovid, and Virgil and Italian classics like Quasimodo, Ungaretti, and Giudici.

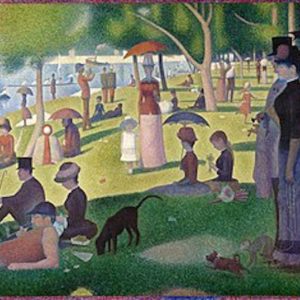

There are quite a few ekphrastic poems in this collection. Why are you attracted to writing about visual art?

Over the years I have found myself returning to the painters—Giotto, the Sienese School, Rembrandt, Breughel, Caravaggio, de la Tour, Van Gogh, Mary Cassatt, Winslow Homer, Braque, Klimt, Duchamp, Picasso, Bacon, and of course my dear friend of forty years, Barry Moser. There’s the image, the painting, there in front of me. What is it saying, without using words? How does it speak to me? And can I translate something there for others to see, though of course it will have to be filtered through the poet’s words. The same is true of music. How do I reveal with words something of how the music touches me? You understand, of course, that the same urge to hear the music of the Word, of creation itself, is present here, not only in the light, but in the darkness as well. Which is what chiaroscuro can do as well.

The theme of pervasive social injustice—and of racism in particular—links several of the poems in this collection. In an era of “virtue-signaling,” how do you write about social justice issues without falling into didacticism or self-congratulation?

The truth is I wake up now each morning, nearly overwhelmed with a sense of the pervasive injustice one sees in the world. Of course, I’d rather wake up to the beauty of things, which is why I go to the window to look out on the trees and bushes and birds—even those damn acrobatic squirrels clowning about down by the feeder—and make a sign of the cross and plead with the good Lord to let the light shine in. And there’s my dear wife of sixty years, already baking scones or our daily bread down in the kitchen, which gives me hope.

But there’s also the injustice of things—racism, the Ukraine, the powerful pummeling the powerless, the scammers looking to make a quick million off the backs of others, the hypocrisy of it all. The last thing in the world I want to project is the sense that I have the answers, when of course I don’t.

As for self-congratulations: Remember that story of the priest in the temple area, congratulating himself on being such a good boy? And that tax-collector, unwilling even to lift his eyes, and praying for forgiveness and the grace to do better? As an old friend reminded me not too long ago, we are all sinners, after all. So let’s get up off the floor and get on with it. I admire those poets who have raged against the dark, but for me, it’s better to point to myself as one who stumbles along, painfully aware he didn’t do more, and trying to get some of it right.

A number of these poems were written during the initial waves of the Covid-19 pandemic. Did that experience of isolation change you or your writing in any way?

The fact is that almost every poem in this collection came about because of the Covid lockdown. I found myself like one of those medieval figures who locked themselves in a small cell attached to the church, chewing bread and drinking the occasional cup of water, and peering out through a small hole in the wall toward the solace of the altar and the living Bread.

Each day Eileen and I spend half an hour going over the daily readings for the Mass. As an extension of this meditation on the Word, for my New Year’s resolution last year I promised myself to write at least one line of poetry every day. The result turned out to be not just one line, but two, then four, then sometimes eight, and onward, revising and revising, armed with old art books, like Bill Williams with that tabletop book of pictures from Breughel when he was in his seventies, homebound by a series of strokes back some sixty years ago.

You have always been so generous in acknowledging your literary masters and influences—and there are quite a few poems in this collection that continue that habit. What might you hope your own influence to be on future poets?

A great question, Greg, and one I’ve been contemplating for some time now. What did I hope to achieve as a teacher all those years ago? And how did the actuality of teaching my dear students change me as well? Remember what Rilke told us: You must change your life. Fr. Hopkins has had a profound influence on me as a poet and as an example. It’s no wonder—or is it?—that our oldest son and namesake is a Jesuit priest. That I used to recite Hopkins’s poems to my infant son (including the Wreck of the Deutschland) while he looked up quizzically from his cradle makes me wonder if that might have had some influence on his decision years later to become a Jesuit.

I’m from a working class family—the oldest of seven—and grew up on the fifth floor of a five-story walk-up tenement on 51st Street in Manhattan (long gone) and then Levittown and Mineola, Long Island, working in my father’s Sinclair gas station and the local A & Ps after school, and even for a while in a dingy factory where I operated a clunky old machine that turned out plastic turtle bowls every sixty seconds hour after hour until finally I sabotaged the damn machine and lost my job (thank God!).

No wonder I turned to Williams and Paterson, the same town where my own Swedish relatives worked in those silk mills on the filthy Passaic a hundred years ago. And when I had a chance to go to Manhattan College and read the classics from Gilgamesh on to the late 1950s, I took it all as a blessing and made it succeed for me.

I mention this because I want my poems to stand as a witness of my time, a mix of the American idiom with the ingrained DNA of my Catholic faith, together with everything from the Psalms to Homer to Aquinas to the entire stretch of English poetry to Mozart and Schubert to Spanish and Latin American poetry and Black Jazz. I often use humor, because there’s nothing like a good joke, even if it has a bit of trench humor in it to get you through the day. Yes, there’s the dark side of things, for sure. But, always, there’s hope.