…but the Lord was not in the wind: and after the wind an earthquake; but the Lord was not in the earthquake: And after the earthquake a fire; but the Lord was not in the fire: and after the fire a still small voice. —1 Kings 19: 11-12

I’ve heard that still, small voice two or three times in my life—maybe. It’s always been at the end of some spiritual crucible, when one of those invisible presses that I encounter sometimes has sufficiently crushed my ego to extract a drop of some essential oil, and I emerge suddenly able to hear with fresh senses, and the voice is there, speaking to me quietly in primordial measures, patiently explaining to me how I should see things.

Moments like those really are gifts, but I do get the feeling that that still small voice isn’t miserly about speaking—that in all probability it is always speaking, and I’ve just cultivated a life with too much interior noise to let myself hear it. This state of affairs is of course regrettable, and there’s a lot of spiritual literature out there about the daily practice of quieting down that noise, about cultivating a disposition to hear that voice. But I’d like to ask a slightly different question: what does that still, small voice “sound like”? Obviously we should be listening for it—always, unceasingly—but what are we listening for? What is it like to hear it?

I’d like to offer a suggestion: that it’s like seeing a difficult work of art for the first time. When I say that, I’m using a number of loaded words, notably that ‘seeing’ that I’ve italicized. I intend (with the italics) a sense of the word where it’s quite possible for me to be standing in front a work of art, to be looking at it, and to be able to visually inspect every inch of it, and yet fail to see the work. I can be blind to something essential in it that I might come to see later, so that although I looked at it once, I saw nothing, and now something essential in the work has come into view, and I am able to see the work for the first time.

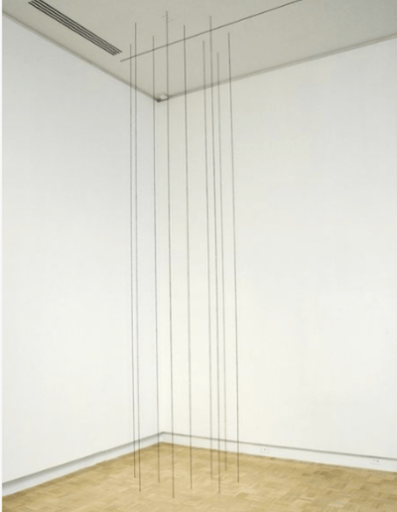

I also have something specific in mind when I describe seeing a “difficult work.” I mean by this one of those works I’ve encountered in my life that is utterly incomprehensible for some reason or other. I think of a work like an untitled yarn installation by Fred Sandback that I saw in one of the minimalist galleries in the Indianapolis Museum of Art. It’s the kind of work that many a museum-goer will look at and shrug their shoulders in bewilderment. Twelve strands of yarn are strung from the ceiling to the floor in a simple cross pattern. So what, I thought? What was there to see? I had no idea.

This thing, these black strands of yarn in a white room, they weren’t registering as anything worth looking at, they were incomprehensible as anything potentially meaningful. They were not what I expect to see in an art museum, but there they were. Suspecting that there was probably something there to see, I gave them my attention. And at some point, as I was walking around them, I caught a glimpse out of the corner of my eye of something that was there, something to see.

Moving around the column created by the yarn, watching the intervals between the strands of yarn shift with my changing vantage point, something snapped into visibility as the space “contained” by those twelve frail lines suddenly felt solid, substantial. It was as palpable as if it had been filled with concrete or carved out of marble, and moving round the threads became as active a vision as watching a dance. The lines sliced through and divided, cut in and waltzed about with the void that had become so unexpectedly visible.

What happened in this seeing of a difficult work of art was that a whole visual order of reality—call it the substantiality of empty space—something that is obviously all around, all of the time but that I had never attended to, was suddenly therespeaking to me in its still, small voice. And that’s the moment I hold onto: that “snapping to” that happens when the thing I had been looking at the whole time—that empty space—becomes something that I can see. It’s not that something is there that wasn’t there before: it’s me that’s changed, able to hear now that voice that always was speaking but that I was thus far incapable of hearing.

*

It’s a pretty common phenomenon: when I say that I’m an artist to people I meet over coffee and doughnuts after mass, they’ll regale me with their incredulity at finding a few pieces of thread stretched from the ceiling to the floor in a Museum of Art. I’m supposed to be incredulous, too.

I always try, very gently, to nudge people who make these kinds of declarations toward opening up their minds a bit, because it is precisely at the moment when I become quite certain that I know what art ought to look like, and that I trust my own incomprehension of a work as definitive evidence of its shortcomings as a work, that art ceases to be able to surprise me anymore. It is precisely at this moment that I become unable to be struck by a vision that is not my own and so seal up the doors and windows of my imagination, draw the blinds and turn on the AC against the heat—it is at this moment that I cease being able to grow in an important way, that I declare that my pilgrimage on earth is over and that I will be settling here, thank you very much, where it is at least somewhat comfortable.

This kind of hostile conservatism when it comes to the arts is not necessarily indicative of spiritual sloth—it is true that we cannot all be ardent seekers in all things. But I think there is a way that an openness—openness to those serious, difficult works of art that are easier to mock than to take seriously—a way that openness can act as a training ground for the spiritual battlefield (if they do not yield spiritual fruit themselves, which I believe they oftentimes do). For as I learn how to open my eyes and ears to those invisible worlds around me that are right in front of my eyes, I’m training my attention to be able to register the speech of a particular kind of voice.

It’s not the voice of the wind, or an earthquake, or a fire. It’s not the much-liked or much-shared voices of the virtual interfaces. It’s that other voice, that voice of someone that’s not me, that I am perhaps afraid to listen to but that I know I should be listening for, that voice that is audible, or will become audible, if I manage to train my ears, and pray to be gifted with hearing.

Tom Break is an artist, writer, and co-creator of In the Wind Projects.