I went on an Anthony Trollope binge last year. It still seems a guilty pleasure, an unexpected detour in my reading list. My literary tastes are more Elizabethan than Victorian, and Trollope’s novels are thick, juicy slices of Victorian sensibility. I had read The Warden, the first installment in his Barsetshire series, several years ago, motivated at the time by several of Stanley Hauerwas’s essays, full of exuberant praise for Trollope’s gentlemanly fiction. Hauerwas’s choice struck me as odd—coming from an American theologian, the son of a West Texas bricklayer, and the most cantankerous pacifist alive—and I wanted to see what the fuss was about. I found The Warden interesting, rich in characterization if slender in plot. I wasn’t overwhelmed, but I promised I’d read more soon. Soon turned into years.

Last year, my wife suggested I read Can You Forgive Her?, the first of Trollope’s six Palliser novels. It’s a hefty tome: 847 pages in the edition I picked up. Stephen King, hardly a master of brevity himself, jokingly called the book, Can You Possibly Finish It? My brain is sufficiently addled by electronic entertainments to prefer compact novels to sprawling epics, yet I gobbled this one up. Before year’s end, I had worked my way through ten more. It was like binge-watching a newly discovered TV series with little likelihood of that empty “what do I do now?” feeling that comes after viewing the last episode. Trollope wrote forty-seven novels in all, a canon I’m unlikely to exhaust.

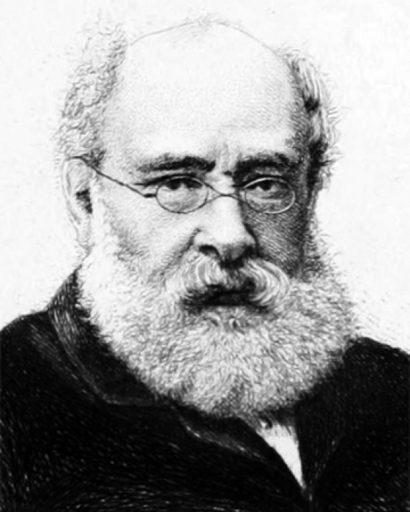

It’s partly that prodigious output that accounts for Trollope’s reputation—now and in his lifetime—as a lesser light than Dickens in the Victorian literary firmament. Born three years apart, Dickens and Trollope unveiled their lengthy fictions in periodical installments for a rapidly growing literate public. Trollope, however, never hid the fact that he wrote, in part, because he needed the money.

Both Dickens and Trollope had troubled boyhoods scarred by a father’s sudden fall into debt. Both knew too well what indignities debt in nineteenth century Britain entailed, yet Trollope never achieved the financial security of the adult Dickens. When Anthony was a boy, his family survived on his mother’s earnings as a writer. Anthony took a position with the post office, in which service he continued for thirty years. It was on the many long train trips his duties required that he first found time to write, later establishing a firm goal of ten full pages every morning before work. Not surprisingly, Trollope’s novels are marked with an inside knowledge of and concern for the daily matters of offices and institutions, including the Anglican Church and House of Commons. W. H. Auden observed that “Of all novelists in any country, Trollope best understands the role of money. Compared with him, even Balzac is too romantic.”

Comparisons with Dickens needn’t end there. Both display a gift for social satire, though Trollope generally maintains a gentler critique of the middle and upper classes while Dickens is often harsher, with a keen eye on the burdens of the poor. Dickens’s plots are more variable and inventive, though few of his minor characters prove more than a concatenation of quirks and mannerisms. Trollope’s plots typically concern courtship and marriage, but his characters are subtly layered, replete with complex motivations. Dickens’s female characters tend to be angels or harpies. Trollope is particularly skilled at rendering women as unique individuals striving for security and agency in a world made by and for men. Indeed, literary critic and Trollope scholar, Shirley Robin Litwin, identifies a woman—Madame Max Goesler from the Palliser series—as “the most perfect gentleman in Trollope’s novels.”

So, what makes reading Trollope a guilty pleasure? Part of the problem is that Trollope is way too much fun to feel serious. He writes in a classic comedic vein, in which the principal characters’ troubles are often resolved with a wedding, though there are notable exceptions. Stanley Hauerwas may credibly argue that the great twentieth century theologian, Karl Barth’s “… main problem is that he didn’t read enough Trollope,” but I worry that Trollope’s relatively privileged characters face the Victorian version of first world problems. Dickens can’t resist indulging in sentimentality, but his subjects and themes feel—and generally are—weightier.

But these concerns are trivial compared to the vein of antisemitism running through Trollope’s later fiction. Ferdinand Lopez, the unprincipled adventurer in The Prime Minister, is obsessed with money, rumored to be Jewish, and described with Sephardic features. Augustus Melmotte, the loathsome financier at the center of The Way We Live Now, also has a mysterious past replete with hints of Jewish ancestry. Ezekiel Brehgert, an otherwise exemplary Jewish lawyer in the same novel, is “fat and greasy.” In The Eustace Diamonds and Phineas Redux, Mr. Emilius, a foreign Jew turned Evangelical Christian huckster, is introduced as “…a greasy, fawning, pawing, black-browed rascal, who could not look her full in the face, and whose every word sounded like a lie.” The list goes on.

I’m not calling Trollope a proto-Nazi or a Jew-hating monster. He, like his characters, is far too complex for that. What we learn of Madame Max Goesler’s past hints at Jewish connections, though we never know for sure. Even a villain like Melmotte is presented as far more than his (possible) Jewishness. It’s worth wondering if Trollope’s lifelong concerns about money and the specter of crushing debt led him to see the British socioeconomic system as the real villain, with anti-Jewish stereotypes serving as stand-ins (as seems the case in The Way We Live Now).

One might also compare Trollope’s Jewish characters to Dickens’s depiction of Fagin in Oliver Twist, who is often referred to simply as “the Jew,” and described as greasy, greedy, and cruel. Dickens, however, dropped such language in later installments of the novel after receiving complaints he had “encouraged a vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew.” Dickens supposedly went on to make further amends in Our Mutual Friend, in which the Jewish moneylender, Mr. Riah, comes off as a plaster saint radiating gentleness and moral perfection.

I realize that to “cancel” all authors of antisemitic language would eliminate most English literature from Chaucer and Shakespeare to T. S Eliot and H. L. Mencken. It’s unfair to judge anyone out of that context. Trollope’s sensibility was shaped by his place and time—just like yours and mine. I trust future generations will judge as accordingly. I’m tempted to relax, cut Trollope some historical slack, and view his faults with the same gentle mockery he viewed his characters’ failings. Yet we find ourselves in a moment of historical re-evaluation, as statues tumble and maybe, just maybe, Americans can begin to imagine a conversation about the role of race and class in the country’s history, though that’s likely wishful thinking.

So, I’m left wondering how troubled by Trollope I should be. Is it wrong to embrace him? Must I disown him? Can I continue to observe from an appreciative yet critical distance? I don’t have an answer yet. I’m not even sure I have the right question. I may never know, but these are among the very things that keep us reading, and for that, I’m grateful.

Brian Volck is a pediatrician and writer living in Baltimore. He is the author of a poetry collection, Flesh Becomes Word, and a memoir, Attending Others: A Doctor’s Education in Bodies and Words. His website is Brianvolck.com