My title comes from a passage in Saint Augustine’s Confessions in which the author recounts hearing a child singing those Latin words, which mean Take up and read! Augustine did so, randomly read Romans 13:13-14, and experienced a profound moment of contrition and conversion. The future bishop, saint, and doctor of the Church was already a voracious reader, one of the most cultured converts the Christian faith has ever won. He interpreted the unusual words overheard from a child as a divine message: the Tolle, lege moment was a particularly intense and significant episode in a lifetime of reading, writing, and contemplation.

The situation I’ve just described and which I’ll return to is the inverse of the one Jessica Hooten Wilson addresses with two books from Brazos Press, The Scandal of Holiness, published last spring, and Reading for the Love of God, just published. Wilson writes as a lifelong Christian to other Christians. She would like more people who profess the faith to immerse themselves in reading works of imaginative literature. Her aim is to affect people at an individual level as well as at the level of communities, including schools. This duology is part of new widespread interest in Great Books curricula and a burgeoning movement in primary and secondary education usually called ‘classical’ or ‘classical liberal arts.’

I said that Wilson writes as a Christian. She also writes as a teacher: as an expert to those who would like to learn. This is a kind of writing we are familiar with in scientific fields, and perhaps still somewhat in history, but not in literature. Holiness and Reading (as I shall call them in brief) are a kind of literary criticism—a kind which one is not taught to write in graduate school or anywhere else but which is essential if literature is to become again a core element of education and not fall into the hands of ideologues. C. S. Lewis was the most successful such popular literary critic of the past century, and I would say Wilson works at a similar task as did Lewis in The Allegory of Love, The Discarded Image, and the essays collected in On Stories. Her work in these two books also reminds me of Dorothy Sayers’s essays.

Holiness and Reading are well organized books that present an amazing range of material, given that combined they weigh in at less than 400 pages. But the material is not scattershot; it is judiciously selected. The Scandal of Holiness focuses on fiction from the late nineteenth through the late twentieth centuries. Each chapter, a close reading, concludes with a brief ‘devotional’ comprising quotations from the text, scripture, and the saints; a prayer of Wilson’s own; discussion questions; and a brief list of further reading. I find this a very pragmatic way of directly engaging the reader. As I said, this is a teacher’s way of writing, and as such quite rare.

Reading for the Love of God has a wider scope. Whereas Holiness is focused almost entirely on what I would call characterological aspects of fiction, which is where one most readily perceives the moral stakes of the art, the second book seeks to deepen our common ideas of reading itself and to recover something of the old allegorical method of reading. A glance at the Great Books list offered at the end shows the sweep of the project. The four figures held up as exemplary readers (two of them I’ve already mentioned) reveal the same: Augustine, Julian of Norwich, Frederick Douglass, Dorothy Sayers. Something important you may take from this wide scope is the sense that when you read good books carefully, allowing and hoping for the experience to change you for the better, you participate in a great tradition.

Holiness and Reading have given me occasion to review my own reading life, present and past, and I find this has been a salutary exercise that has some bearing on Wilson’s project in these books. While I am a Christian, and the parochial school at my parish has recently adopted a classical curriculum, I am in a way not the intended audience for Wilson’s duology. To return to my opening anecdote—and to compare a small thing with something vastly greater—my own background is more like Augustine’s. My upbringing was secular and my schooling through my undergraduate degree was public.

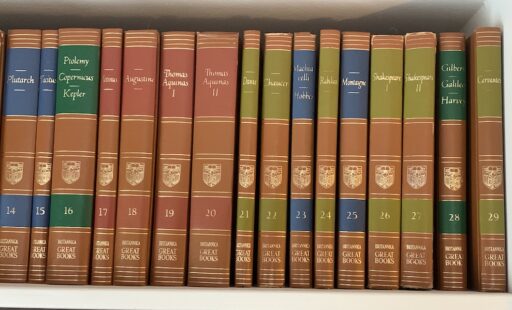

No one ever had to convince me to read the great books of Western civilization. In fact, for my sixteenth birthday my parents acquired a fifty-four-volume set of Great Books published in the 1950s. I still possess the set and keep it on a high shelf (pictured above) in a place of honor, as one does with the Talmud. It was partly due to the influence of those Great Books that I studied literature and classical languages as an undergraduate and went on to study medieval and Renaissance literature at the graduate level.

But in graduate school I became very disillusioned. After five years of working toward the PhD my secular worldview collapsed, and with it my confidence that the secular academy could offer any intellectual paradigm or critical hermeneutic that did not lead to despair. I had absorbed a literary and philosophical tradition that was in its essence and in its greatest achievements profoundly Christian, but I was not a Christian and neither was my scholarship. I found that I had read my way to Christian faith in an institution which precluded it. I did not have a single, epiphanic moment like Augustine’s Tolle, lege, but the arc of my career as a reader, thinker, and writer was similar, and at about the same age as Augustine did (and many others have done) I began to read my way into the Church.

There have always been philistines and prudes, people who want to censor and kick the poets out of the republic. Writers like Joachim du Bellay and Philip Sidney and Percy Shelley will always have to write defenses of poetry. Reading is dangerous: it strengthens and grounds you even as it makes you vulnerable and open to the world, to life, to the source of all worlds and all life. I believe Jessica Hooten Wilson’s project in the two books under consideration ought to and must be successful because I’ve known the reading she champions not as the fruit and encouragement of faith, which is what these books show reading may be, but as preparation for it.

I want to end by remarking on a crucial aspect of this duology. Jessica Hooten Wilson is unafraid to voice deep suspicion of the screen. All screens. The deluge of digital entertainment, opinion, distraction, corruption—in a word, virtuality. She recognizes, in these books, that if people are going to read more and better, they must give up whatever they are doing instead of reading. And I believe she is right that what people do instead of reading is not anything healthy, like learning to make music or being outdoors. What has replaced reading is a culture of virtuality. But imaginative literature is not virtuality: it is theophany and a means by which we may hone our sense of the created order as theophany.

Jonathan Geltner lives in Ann Arbor MI with his wife and two sons. His translation of Paul Claudel’s Five Great Odes is available from Angelico Press and a novel, Absolute Music, is available from Slant. If you enjoy his posts at Close Reading, check out his new Substack, Romance and Apocalypse, for more frequent and in-depth essays on the places where literature and other arts meet religious ideas and experience.