I have a few rules that I try to follow as a literary citizen: 1) If I want to read a book by a living author, I buy it new. 2) If at all possible, I buy it local. 3) If I can’t buy local, I aim to secure it from a distributor who takes at least minimal care not to defraud authors by selling counterfeits of their work.

I have another literary citizenship rule, originally created for my children, with no anticipation that one day it would be applied to me. Yet, because I hold firmly to the conviction that governing officials ought to bend a knee to the laws they create for others, I find myself bound by it nonetheless. The rule: There is to be no watching of movies by members of my household unless they have first read the book.

I considered this a support-the-arts decree, but over time I found it served a prophylactic function; some movies are based on books so dreadfully written that my children can’t get through them, no matter how badly they want to see Twilight orThe Maze Runner.

But alas, now the rule hangs over my head, preparing as I am to cave to years of relentless pressuring from friends, strangers, and Proper Opinion, and watch Hamilton.

Before you report me to the appropriate tribunal, please understand that my resistance wasn’t due to a suspicion that I’ll dislike it. Alexander Hamilton isn’t necessarily my favorite American founder, and in my pedestrian tastes I have yet to like a musical more than The Sound of Music, but I have no doubt Hamilton will be thoroughly enjoyable, even edifying.

No, my resistance was more innate—congenital, even. The more my betters insist I do something, the deeper I dig in my heels. I know this is unhealthy and unsociable, especially now that we have arrived at our final stage of enlightenment, wherein the proper views on all matters scientific, religious, social, and political have been determined. Still, I like to think my obstinance bears just a tad of the rebellious strain that animated Hamilton and his brethren to tell King George to get stuffed in the first place.

Regardless of excuses, my point here and now is: I’m ready to capitulate. But I’m bound by my own book-first rule, which in turn triggers those other rules about buying new, local, etc. All this is context for what happened next, which is that I went to the bookstore.

Now, in this particular bookstore—one of the few within reasonable range that is neither boarded up nor open at seemingly randomized End-Times hours that bear no correspondence to what’s posted on its website—I’ve noticed that expanding floorspace is devoted to selling video game cartridges and related equipment. Not that I oppose harnessing poor habits to subsidize my reading, mind you.

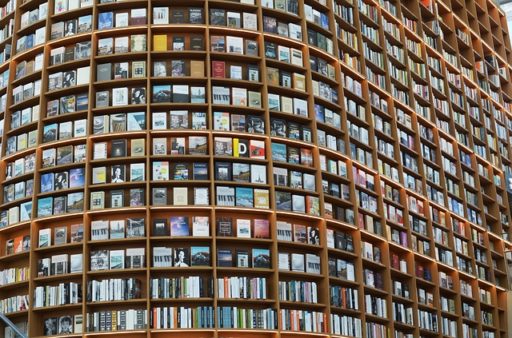

The video game section was indeed bigger and sadder than ever, but it was the book section that proved to be the epicenter of cultural degradation. Whereas before the shelves had been simply demarcated, with labels like “Philosophy” and “History,” and within these a sprinkling of subcategories, now they sported more options than the food allergy list on an Aspen Montessori pre-school enrollment form. It looked like the bookstore had deputized the local homeowners association president with a label maker and an honorary library science degree. Shelves previously clustered under the banner of “American History” were now labeled by narrow decade ranges, trailed by shelves further dissecting the domain into regional and ethnic gulags. Abutted to these were whole other classes of “culture” books which, while presumably taking place within American history, are judged by some circuitous reasoning to be outside it.

The many problems stirred by this fine-parsed method begin with the practical. Suppose you’re looking for a book on Jim Crow, for example. Do you go to the 1870-1890 shelf? Or perhaps, remembering that Woodrow Wilson segregated federal facilities in 1913, you should go to the 1900-1920 shelf. Or to the decades leading up to Brown v Board encompassed within the 1930-1950 shelf. Or could it be in “African-American History?” Or maybe “Southern History?” Or in the Culture subcategory called “Race?” Or maybe “Critical Race Theory?” How about “Civil Rights?”

Practicality aside, this felt like a personal affront, apiece with the divisive work of political operatives and social media consultants and other dark-arts technicians: parsing and slicing and classifying and subcategorizing, everyone in her place and every one of us with a label, our overseers noting our every twitch in their clipboards, gleaning manipulation triggers from our text messages and Google searches and whatever Siri and Alexa and Zoom whisper to their creators about the inner workings of our homes.

My profile is probably labeled something like: Disaffected Middle-Aged Quasi-Intellectual White Male BBQ Chip Eater with Burgeoning Paranoia Who is Not Amused by GIFs. Or maybe I belong in American History, Shelf Five, Years 1976-1984, shaped as I am by Marathon Man on one side and Red Dawn on the other, deeply suspicious that bad people are getting away with it, while worse people yet parachute onto our rooftops.

Regardless of the specifics, as any of the myriad programs tracking how quickly I quit instruction manuals and mandatory sensitivity training videos will confirm for the proper authorities when my time comes, I also belong in the bin labeled: Low Tolerance for Bullshit.

Meaning I left the bookstore without buying anything, in as much of a huff as a grown man can muster behind a mask of cotton that, before pandemic retooling, had been destined to become someone’s underwear. And when I got home, I threw the rest of my literary citizenship manual out the window, because this not-the-boss-of-me obstinance sometimes extends, unfortunately, to myself.

In other words, I bought the damn book on Amazon. Three days from debarking to a remote location just shy of the Canadian border to read and fish, I find convenience trumps citizenship. It gets harder to be a good neighbor as these categories—rooted in facts, but not the full truth of us—obstruct one’s vision. Harder not to see labels where once were stories.

So who knows, maybe I’ll wander across one of those streams to the other side. See how our northern cousins are faring. Learn to like poutine and hockey, build a little cabin, and perhaps one of those tiny libraries on a post out front. It won’t hold much, but its shelves will be unlabeled, save for a single word up top: “Free.”

Tony Woodlief lives and writes in North Carolina. His short fiction has appeared in Image, Ruminate, Saint Katherine Review, and Dappled Things, while his essays about parenthood and faith have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Comment, and The London Times. He runs a website for fathers called Intentional Fathering, and can occasionally be found on Twitter.