My nine-year-old daughter loves informational texts: vibrantly colored kid encyclopedias teeming with animals, Roman architecture, Bible history, anything of the sort. “Dad! Did you know…?” is the ubiquitous sound that pops joyfully from the backseat on long drives. As a pastor and English teacher, I’m happy she’s so bent. It’ll do her good in school.

Recently, she’s gotten tall enough to sit in the front seat and, with it, has discovered a new subgenre. In subtle and rapt joy, she is working through the stock glove compartment canonical tome, “Prius C 2014 Owner’s Manual.” This is not a desperate act in the wake of running out of screen time; this reading is not for business or busyness but for pleasure! And because of that, I am afraid she might grow up to be a theologian.

My daughter’s latest literary interest is not wrong, but it is potentially hazardous: she might think she knows how to drive at the end of it. Theologians and the more academically minded Christians among us have the disturbing ability to speak of the Word-Become-Flesh in a disembodied, unstoried way. The books we write about books, especially the Bible, can become two degrees of separation from anything remotely God-breathed, which is painfully ironic considering the incarnation. (Doubly so, considering this is a review of a book drawing from the themes of another book.)

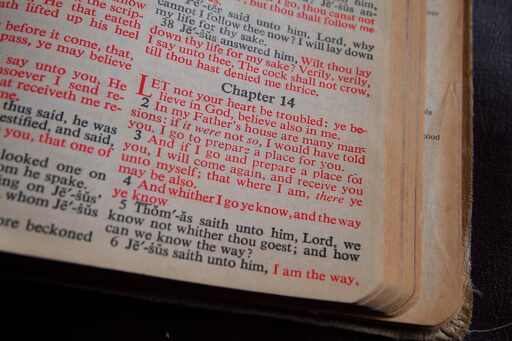

I believe our love of categories is largely to blame. Slice open a frog or parse a Hebrew verb, and in the end, they are both dead—with all of their internal organs clean and categorized. The real problem is not that the frog is dead; that comes with the territory. The problem is hidden in the smug way that categories tend to deceive us. Each parsed part of the poor Hebrew noun in its Strong’s formaldehyde jars is necessary in its own right. It’s just not enough. Frogs swim, and scripture breathes.

Then there is the rare book about scripture whose very words make one’s breath catch sharply. A frog jumps in, the sound of water…

Enter Frederick Buechner’s Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale, which explores the Christian gospel through the lenses of three literary genres: tragedy, comedy, and fairy tale. In essence, Buechner suggests that serious matters of the gospel are first matters of a human life well lived before they are a logical problem to be solved and systematized. Thus, he encourages readers to engage with the gospel not only as a doctrinal or moral teaching but as a compelling and rich narrative that speaks to the depth and diversity of the human condition. In keeping with this project, the book’s form embodies his thesis.

To borrow from Marshall McLuhan, Buechner’s medium is his message. The book is an experience more akin to Saul’s Emmaus road catastrophe than to Paul’s Mars Hill monologue. In short, Buechner’s book breathes.

At first glance, one could easily misread the subtitle as a typical formaldehyde-laced sermon outline: three points about the gospel in neat, sanitized categories. The problem with such an assumption is that tragedy, comedy, and fairy tale are not the kinds of categories one would expect. I admit I originally felt ‘fairy tale’ was nothing more than cheeky book cover clickbait. Nevertheless, it enticed me enough to rescue it from Goodwill despite its red tag not being the half-off color of the week. What kept me reading was Buechner’s uncanny attention to the human experience told in the prose of a true artist.

Few people are transformed by even the most erudite charts of narrative parallelism. Rather, we are gripped and dragged into being by living light. Such light is not a matter of photons but of living people. Sown throughout Buechner’s incisive apology for a greater depth of truthfulness from the pulpit are vignettes of mean, crooked, and broken people. They stand not as proof texts but as proven lives to the mystery that is truth-telling in all of the purity and meanness that honesty demands.

Before my eyes, as Jesus stands before him, “Pilate let the cigarette smoke out of his mouth to screen him a little from the figure before him,” and “Job sits at the table with his head in his arms so that he won’t have to face the empty chairs of his children.” Characters I have read thousands of times are infused with a fresh, resonating life. This is the particular magic of Buechner’s prose and, I suppose, the true sense of scripture: an uncanny witness to life.

We are all Job and Pilate screening ourselves from the concrete truth of the living Word and the cryptic silence of death. The gospel is the message of a Nazarene whose face was set like a flint toward his victorious demise. That unwavering gaze into tragedy is the very thing that calls us to live truthfully.

And yet, Buechner doesn’t leave us alone with Job in his cold dining room, rather, he insists that truth goes beyond tragedy to reveal a “joy beyond the walls of the world more poignant than grief.” A stone rolls away from a tomb, a phoenix is born from its ashes, and a child’s faith is confirmed.

I find this is the most compelling and repulsive aspect of the way of Jesus: a truthfulness that does not dismiss irrational pain with trite distractions and invites us to remain childlike. We’d all rather trade our weeping for distraction than joy. Joy is come by honestly, and honesty is much more than tragedy.

Buechner unwittingly best explains his approach to writing when describing Jesus’s teachings as “not in the incendiary rhetoric of the Prophet or the systematic abstractions of the theologian but in the language of images and metaphor, which is finally the only language you can use if you want not just to elucidate the hidden thing but make it come alive.” It makes sense then that Telling the Truth would follow suit. A servant isn’t greater than his master, and that is what we find: a masterful book in the service of the gospel.

Abe Figueroa is a speaker, writer, editor, and teacher living in his natural habitat: Portland, Oregon. His rich prose explores the sacred in the mundane, inviting readers to rediscover the gift of living that is all around them. You can find him at abefigueroa.com.