My friend and colleague Robert Garis died in January 2001, age 75. He began in the English Department at Wellesley in 1951, and for four decades, he was a powerful presence as a teacher and advocate for the study of literature.

Bob was a superb close reader, maybe the best I have ever met, vivid and exact in his responses to literature, and to film, ballet, and music as well. I admired Bob tremendously, his seriousness and intensity, and his joy too, his pleasure in being in the company of exceptional authors, composers, directors, and choreographers. Bob taught courses on many of them, and he wrote brilliant books about Charles Dickens, George Balanchine, and Orson Welles.

The challenge, for those of us who knew Bob, was that he could be a difficult person to be around. He was capable of warmth and affection, but he believed in making judgments—what’s good and what’s not, what works and what doesn’t. He said what he thought about a novel or film, and it was hard to express a judgment different from his. He liked argument; he wanted to hear whether you agreed with him or not. Sometimes, however, the position Bob was stating took on a life of its own. He seemed not to perceive how imposing he could be, and how hurtful.

It’s far back in the past, but I remember it as painfully as if it were yesterday. I was a young assistant professor, and part of the process at Wellesley was that senior faculty had to attend some of my classes, write reports about them, and meet with me for discussion. These class visits were intended to help new faculty become better teachers, but they also were evaluative, part of the reappointment and tenure system. Bob’s temperament made his visits highly evaluative, as I found out when he came to two class sessions of my Shakespeare survey and made clear to me in his report and meeting that he thought I had done a bad job.

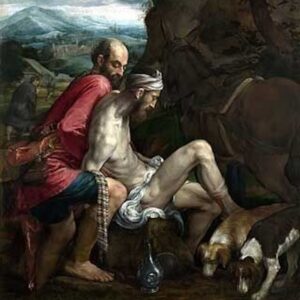

I was teaching Othello, one of my favorites, a play I knew well. I’ve always been enthralled by the exalted conception of himself as warrior and lover that Othello voices, and that Shakespeare brings alive through thrilling lines and speeches—a conception that begins to disintegrate when Iago devotes himself to dismantling it.

That’s the interpretation that in my apprentice-like fashion, I tried to explain and demonstrate to the students. As soon as Bob’s two visits were done, he told me briefly but firmly I was mistaken. It’s not that Iago destroys Othello, not really, because in truth the enemy is not without, but within. Othello is limited and superficial. He doesn’t collapse because of Iago’s malice and deceitful expertise, but, rather, because he lacks awareness and understanding. Othello thus is the agent of his own downfall.

Bob believed I was teaching the students an interpretation of the play that was wrong. His written assessment was severe, and his meeting with me was a reprimand.

We met at lunchtime in the faculty dining-room. An uncomfortable greeting, followed by awkward chat while I poked at a salad and tried to eat pieces of a roll. There was a nervous-making pause, and then Bob got going in a surge of sentences I could tell he had been forming, and holding back, since he had attended my classes. I wondered whether others in the room could hear Bob’s words; I was sure they could see his agitated hands in critical motion. What he told me was wounding, and it brought tears to my eyes.

I recall this experience with traumatic clarity, and when I tell others about it, they say that Bob was cruel. But he wasn’t cruel, at least he did not intend to be. This was who Bob was.

I’d like to share with you Bob at his best, which I hope will prompt you to look up his books and learn from them and admire him, as I did and still do. Here, from The Films of Orson Welles (2004), he focuses on a passage in Macbeth, a play Welles adapted for the screen. A bloodied soldier reports to King Duncan, praising Macbeth’s feats in battle:

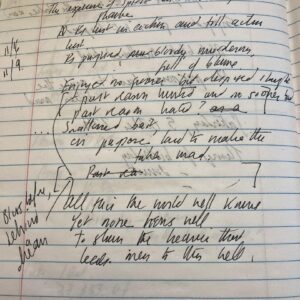

For brave Macbeth (well he deserves that name), Disdaining Fortune, with his brandished steel, Which smoked with bloody execution, Like Valor’s minion, carved out his passage Till he faced the slave; Which ne’er shook hands, nor bade farewell to him, Till he unseamed him from the nave to th’ chops, And fixed his head upon our battlements. (1.2.18-25)

And here is Bob’s analysis:

The reason this scene, particularly the quoted speech, should be saved is not because it makes particular points about character or action, but because of the power of its imagery, even though it is hard to be certain just how these unnervingly savage images of bloodlust actually function in the play. The voluptuous sensuality of “smok’d” and “carv’d” and “unseam’d” exerts a dangerous temptation, inviting us to take pleasure in the glamour of bloodshed and the thrill of mastery over helpless human bodies at our mercy. And the images are virtually free-floating; we might expect them eventually to be placed in some exact relation with Macbeth’s murder of Duncan, but nothing of that sort develops.

On the face of it, there ought to be a connection between Macbeth’s words and the fact that he later actually does “carve” Duncan, and actually makes his “brandish’d steel” smoke “with bloody execution,” but this is a connection that play doesn’t really make, Even Ross’s all but clairvoyant praise of Macbeth as “Nothing afeared of what thyself didst make/Strange images of death” (1.3.96-97) doesn’t have the effect of foretelling Macbeth’s murder of Duncan—one senses a connection, yes, but it’s elusive.

We are dealing with the typically Shakespearean habit, method, and skill; these vivid images don’t describe Macbeth’s character in particular or his way of killing in particular, but instead are generalizing images describing how any great and victorious soldier would perform. The characters speak from and about a world of war in which such barbarism is simply what happens.

Soon afterward, Shakespeare smoothly shifts the emphasis, without notification, having Duncan praise Macbeth in the language of a world far closer to ours: “O valiant cousin! Worthy gentleman!” (1.2.24)—not quite appropriate words for describing a soldier who fixes his enemy’s head on the battlements, yet we don’t really pay attention to the difference. Shakespeare is deeply and unflaggingly interested in character, but his art is never more flexible and interesting than when it is dismissing our awareness of a character because it is useful to do so at that moment, bringing it back when that in turn is useful.

There it is: Bob’s intelligence, imagination, and force of personality operating in response, inquiry, and judgment. It was a rare gift he possessed, and a complicated one. All of us esteemed Bob and sought his approval. This was the case even though we knew he was inimitable, that no one could write and teach with his decisive authority and impact. Bob was a great critic, he had a kind of genius, and I wanted to teach and write like him. It took me a long time to realize I couldn’t.

William E. Cain is Mary Jewett Gaiser Professor of English at Wellesley College, where he enjoys teaching courses on Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and other American writers. His recent publications include essays on Edith Wharton and Ernest Hemingway.