I’ve always liked the paintings and really all the art of Spaniard Joan Miró. You could call the art Surrealist and Miró was undoubtedly part of the Surrealist movement and spent much time with the French Surrealists and that’s an undeniable part of art history. Still those kinds of categorizations only get you so far. Myself, I like to think of Miró as an earthist. This is not such a facile term and I apologize for it.

I just mean that Miró was obsessed with the earth, in every sense of the term. He liked to paint earthy things. That’s to say, objects of everyday life. Critters, creatures, trees, things in the garden, stuff to be found on tables. As he matured as an artist, he would also paint things that I would describe simply as lumps of indeterminate stuff. Creatures that aren’t quite identifiable though have characteristics like, maybe, horns or wings or tails that one can associate with various known creatures. He liked to paint things, both living and inanimate, as veering into the territory of becoming just blobs of matter with only the barest hint of form.

He liked to see everything as being claimed by the earth, being claimed by the raw stuff that can be molded into this or that. A blob of earth might become a tree or a person or a bird. But all the specificity in the world won’t change the fact that, at its core, the person-blob or bird-blob or plant-blob is an earth-blob that could just as easily have transformed into another sort of thing. There are, therefore, a lot of individual thises and thats on the canvases of Joan Miró. But there is no this that couldn’t easily become a that and vice versa.

So many of the canvases of Joan Miró are quite cluttered. And why shouldn’t they be? The earth, at ground level, is indeed quite busy with all manner of clumps and blobs of formed earth-stuff that takes on various shapes and grows and changes and transforms and then sinks back into the formlessness from whence it came. Miró made pictures of that. Snapshots of the coming and going of the blobs.

But he also noticed, we should mention, that the cluttered space just around the surface of the earth and all the emerging-out-of-matter and dissolving-into-matter could be described as being framed by a rather striking emptiness. That’s the sky. Or, in more proper Miróian terms, the forming formlessness of the heavens. Miró sometimes put this strange emptiness into his paintings too. Because how could you not? It seems important. If it was just clutter all the way up and all the way down then we’d have nothing to actually notice the clutter by. The non-clutter makes the clutter the clutter that it is. Not that the cosmos is only empty, by the way. There is a ton of stuff out there, too. Miró was not an idiot. He saw the stars. And he made some paintings that note the comings and goings of the heavenly objects.

But he was acutely aware, nonetheless, that although the cosmos is itself a busy place, that busyness is not always, not even usually, so apparent to the busy blobs of stuff merging and intermingling down around the crust-level of the earth.

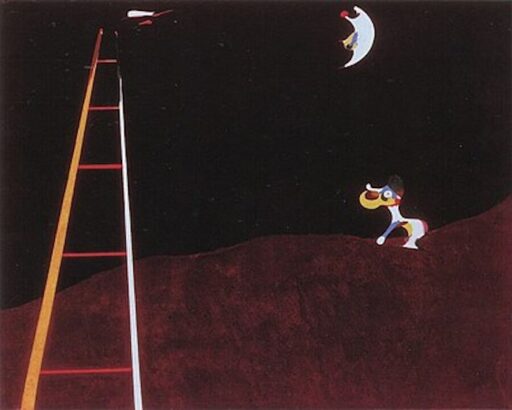

And so we sometimes get paintings by Miró like Dog Barking at The Moon. This painting is obviously, by the way, a reference to a painting every Spaniard would know, and which was painted by Goya in his later years and which is now often known simply as El Perro, or The Dog.  Goya’s dog is really just the small face of a dog peeking out and up from behind an indeterminate muddy hill of some sort, framed against a murky and most-depressing brown sky. Miró reproduces his own version of that murkiness in the hill that his own dog stands upon as it barks at the moon. In both painters, this mound of brown is the earth, the overwhelming weight of it. But here, in the two dog paintings, the weight and heaviness, the sheer mass of matter is offset and made even more what it is by the counterbalancing weight and power of something which is without any particular mass.

Goya’s dog is really just the small face of a dog peeking out and up from behind an indeterminate muddy hill of some sort, framed against a murky and most-depressing brown sky. Miró reproduces his own version of that murkiness in the hill that his own dog stands upon as it barks at the moon. In both painters, this mound of brown is the earth, the overwhelming weight of it. But here, in the two dog paintings, the weight and heaviness, the sheer mass of matter is offset and made even more what it is by the counterbalancing weight and power of something which is without any particular mass.

There are two kinds of almost overwhelming formlessness, is what I am saying. There is the formlessness of matter (earth) and the formlessness of emptiness (sky). These two forms of formlessness vie with one another in their claims to be absolute. But what about the dog? The dog has no chance. That’s what’s so funny about Goya’s painting, which is not always recognized as a comedic work, though I would argue quite vehemently that it is. Anyway, Miró agrees with me. Because Miró’s dog is a little bit silly, more obviously silly than Goya’s dog and even clown-colored, you could say. Miró’s dog barks at the moon, which doesn’t care, and looks across at a ladder that goes into the sky.

You can imagine Miró’s dog barking the words “How awesome is this place!” in a bark that conveys both wonder and some amount of fear, because we could translate the word ‘awesome’ also with ‘dreadful’. That’s to say, this is an encounter with the sublime, or whatever you want to call it, when a creature suddenly catches a glimpse of the formlessness of matter framed by the formlessness of emptiness. And there is a dog. Because there is always a dog. The dog understands nothing, but doesn’t have to. All the dog really has to do is just to be there, to look up, or to bark a few times. The earth will claim the dog one day and the earth will reblobulate another dog another day. Dreadful, awesome, hilarious.

Morgan Meis has a PhD in Philosophy and is a founding member of Flux Factory, an arts collective in New York. He has written for n+1, The Believer, Harper’s Magazine, The Virginia Quarterly Review and is a contributor at The New Yorker. He won the Whiting Award for non-fiction in 2013. Morgan is also an editor at 3 Quarks Daily, and a winner of a Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant. A book of Morgan’s selected essays can be found here. His books from Slant are The Drunken Silenus. and The Fate of The Animals He can be reached at morganmeis@gmail.com.