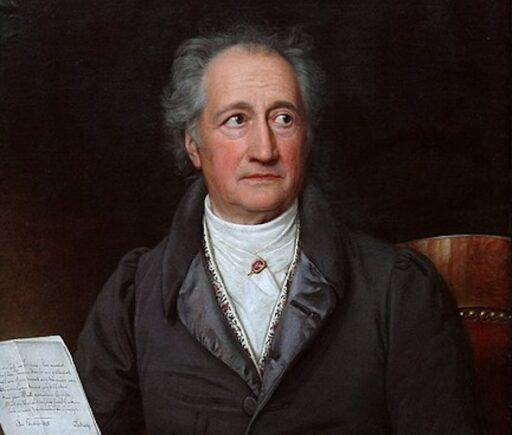

I was reading some Goethe recently, both in German, since I’m constantly working on my German these days for reasons not entirely clear to anyone, myself included, and also sometimes in an English translation, since it is pretty hard, actually, to read Goethe in German given the somewhat antiquated and very much literary nature of the writing. Actually, come to think of it, I haven’t really been reading Goethe. What I’ve been reading is the account of many long and short conversations between Goethe and a person named Johann Peter Eckermann, who was a youngish literary-minded fellow who sent Goethe some of his writing, writing that was rather ass-kissy in its love of, and reliance on, a Goethian way of thinking, and so Eckermann sent Goethe some of this Goethe-worshiping writing and Goethe, unsurprisingly, lapped it up and invited Eckermann to come and visit him at his fancy house in Weimar. This was in 1823 or thereabouts. Goethe was born in 1749, so this would have made him seventy-four when all this business with Eckermann took place. And then Goethe died in 1832, so there were roughly nine years of Goethe and Eckermann talking and talking and talking. The German edition of the conversations is multiple volumes and the Penguin English translation, which I think is complete, comes to 648 pages in fairly small print.

The funniest thing about the book is that Nietzsche was completely in love with it. He mentions in several of his writings what a great work of literature it is and praises the thoughts and ideas of the seventy-four-year-old-and-older Goethe repeatedly. Okay, you might not find this very funny. But it’s funny because the conversations between Goethe and Eckermann are quite staid and, I don’t know, more or less conservative. There is none of the wildness and radicalism of Nietzsche in what Goethe and Eckermann talk about or in the way that they talk. So it’s amusing that Nietzsche was so pleased with these conversations. Was Nietzsche more German, in the end, than he realized or liked to admit?

Because there is something incredibly German in the conversations, something inherently orderly and, I don’t know, structured. Not that Germanness can be boiled down to order and structure. That would not be fair. But the conversations are all about the right way to be, the correct way to think about different kinds of art, the proper comportment toward nature, the civilized way to behave in this or that situation.

Actually, when I describe the conversations between Goethe and Eckermann I’m describing something that in most cases I’d be completely uninterested in and probably would actually loathe. And yet, I don’t loathe these conversations. I don’t think I love them as much as Nietzsche did but I am charmed by these conversations. Even the sycophantish Eckermann becomes more and more lovable as you read, especially in the German, though for reasons I’m not sure I can explain. Somehow the whole thing is indeed at its most charming in the German, at least in the exchanges where the German isn’t so insanely difficult that you have to look up every other word.

Eckermann essentially never ceases in his praising of Goethe and in his licking of the Goethian boot. And yet, we love him for it. I suppose we love him for it because his utterly open and basically childlike worship of Goethe puts the old genius at ease. And then the old at-ease genius gets to talk and talk. With most people you don’t want to let them prattle on for nine years. Nine minutes is enough for most people, to be perfectly and perhaps brutally honest. Maybe less. But Eckermann egged the self-important old genius on for nine entire frickin’ years. And then here’s the crazy fact: Goethe is actually up to the task! Not always. The conversation has its ups and downs and also I should be completely honest here in that I haven’t read the whole thing and I’m slogging through the German edition quite slowly. Also, I jump around in the book. I don’t read it linearly in the English. I do in the German. But in the English I jump, which I almost never do.

Anyway, Goethe says all kinds of things I completely disagree with personally and sometimes says some stuff that is verging on insane. His theory of colors is interesting from a historical and from an aesthetic standpoint. But as an actual theory of color, which it is supposed to be, it is nuts. Goethe’s idea of why the Greeks were so great is utter fantasy. He seems to think the ancient Greeks had some sort of perfectly natural and coherent society, that it was a picture of health and immediacy. Pure fantasy.

But then you’ll find a nugget like this one from Thursday, 12 February 1829:

Goethe read me the splendid poem he had just written, beginning ‘No being can decay to nothing…’ etc. ‘I wrote this poem’ he said ‘as the antithesis of the lines “for all things must decay to nothing, if they would remain in being…” etc., which are stupid, and which my Berlin friends, to my annoyance, saw fit to display in gold letters at their recent meeting of natural scientists.

The poem Goethe is talking about is Vermächtnis (Legacy), and the lines he is repudiating are from his earlier poem, Eins und Alles (One and All). So, Goethe is basically making fun of himself here, though it is also something in the way of a humble brag, since he manages to mention that a bunch of scientists etched his words somewhere in Berlin in gold.

The difference, by the way, between saying no being can decay to nothing and that all things must decay to nothing is really a direct glimpse into the war within Goethe between his Romantic impulses and his Neoclassical impulses. I’ll always, personally, prefer the Sturm und Drang Goethe. But Goethe will always be great because of the war that raged in him, and the result of that war was that he often upbraided himself for his own stupidity. Delightful, actually, and we would never have had such a direct glimpse into Goethe’s contradictory soul without the slavish, adorable sycophancy of Johann Peter Eckermann.

Morgan Meis has a PhD in Philosophy and is a founding member of Flux Factory, an arts collective in New York. He has written for n+1, The Believer, Harper’s Magazine, The Virginia Quarterly Review and is a contributor at The New Yorker. He won the Whiting Award for non-fiction in 2013. Morgan is also an editor at 3 Quarks Daily, and a winner of a Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant. A book of Morgan’s selected essays can be found here. His books from Slant are The Drunken Silenus. and The Fate of The Animals He can be reached at morganmeis@gmail.com