In yesterday’s post I suggested that the eroticism of Rough and Rowdy Ways is like that of the Song of Songs, and when Dylan writes love songs that are entirely affirmative, declarations rather than castigations, such as “I’ve Made Up My Mind To Give Myself To You,” I think that’s the connection to make.

But eroticism is essential in the prophetic passages of the Bible too. There, it is a unique and enormously powerful erotic idea, holding as it does between a land and people on the one hand, and God on the other.

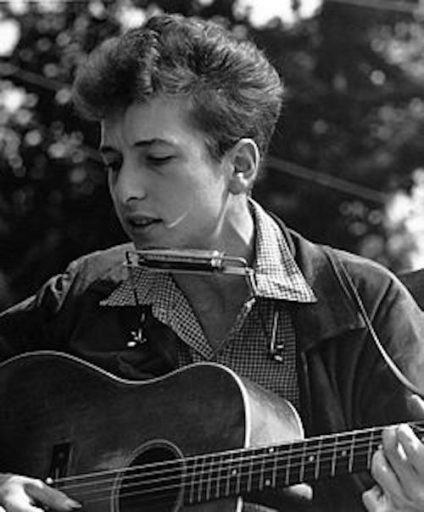

The desire that is typical of Blues—from which Bob Dylan draws so much of the spirit of his music as well as actual phrases—is the same we find in the prophets. The Lord God is a jealous and often a jilted lover. What matters most to the biblical sensibility is Eros in the mode of adultery. Whether between the Lord and Israel, or Christ and his bride the Church, the chief concern of biblical writers is fidelity or the lack thereof. Promiscuity is a fixation of Hosea, who seems to provide some of the most mysterious lines of the album, in “Key West”:

Twelve years old, they put me in a suit, Forced me to marry a prostitute There were gold fringes on her wedding dress That’s my story, but not where it ends She’s still cute, and we’re still friends Down on the bottom, way down in Key West

In the Bible, Hosea is forced to marry a prostitute, and so enact and embody Israel’s deviation from the ways of the Lord. The language of adultery (always a version of idolatry according to biblical logic) is perhaps most famous from Jeremiah, but it is fundamental to all biblical Eros. In the New Testament the fascination with sexual fidelity runs the gamut from Jesus’ disregard of the woman caught in adultery (but “go and sin no more”), to the cosmic harlotry that colors Apocalypse.

But so far I’ve been thinking in terms of content. Bob Dylan has always been about style—a multiplicity of styles—from clothing and interviews to his manner of singing and the poetic style of the lyrics, and that means he has always been about playing a role. Just as there is no one who does not occupy some position, play some role, in a culture—even the role of outlaw or outcast, sacred victim or scapegoat—neither is there is such thing as a style-less language or literature.

The three main songwriting traditions that Dylan draws upon in his lyrics are 1) the British ballads, which migrated to America especially in the Appalachians and later all through the South and West; 2) Gospel and other American Protestant spiritual music, much of which has its roots in Black American history and culture and all of which displays a high proportion of Old Testament references; 3) Blues, the influence of which is hard even to suggest, so pervasive is it throughout Dylan’s work, including in the tragic and elegiac worldview that informs so much of what he has recorded.

Dylan has composed in complex strophic forms like the Troubadours to whom he has been likened. He has made use of the ballad stanza, and of the Blues stanza. Somewhat surprisingly, though, the way I hear a great deal of Dylan’s music, especially the late style, is in the form of irregular but often longer, aspiratory (i.e. breath-governed rather than metrical) rhymed couplets. This is not a prosody that has worked in English on the silent page since the eighteenth century, but it works for Dylan, no doubt because with music and breath as guides, rather than the rules of plodding pentameter, he can balance and enrich the couplets.

Take as an example these lines from another great, late geo-prophetic piece, “Mississippi,” from the 2001 album Love and Theft. These lines of twelve and fourteen syllables show four beats in the first and maybe six in the second:

Well the emptiness is endless, cold as the clay, You can always come back, but you can’t come back all the way

That first line, with its balanced alliteration, could be a line of Old English poetry. This is how the lyrics are posted on the official website. Often lyrics that could be written out this way are instead transposed the way they sound on the record, broken at the caesura:

Well the emptiness is endless,

cold as the clay,

You can always come back,

but you can’t come back all the way

The variable couplets can be folded up to make a modified quatrain or ballad stanza, if the musical rhythm implies such.

Finally, I would note that Dylan’s late style is one of allusion, proverb, quotation, cliché. Sometimes he gives new life to cliché by means of ambiguity: is that “come back” like coming back from apparent defeat in a game, or is it geographical return? Either way, the meaning is amplified by the repetition with qualification, but for all that it is still the cliché “You can’t go home again” or “You can’t step in the same river twice.”

Other times Dylan will enliven quotation or proverb with surprising rhyme (e.g. on the new album he rhymes “Holy Grail” with “betrayal”). All this can be aggravating for those who associate the poetic solely with the novel and innovative. Really it’s the method of the folk artist, the artist who works with what is traditional, which is to say commonplace.

The artist of allusion, quotation, proverb, and cliché is fundamentally one who eschews identity in favor of role. He sings things you’ve heard before, and so you know he is playing a familiar role. This brings me to the reason Dylan’s music has been ringing in my ears more with each passing week and month and year. I feel the whole country, the whole culture, tilting (from right and from left) into identitarianism, and I just don’t believe in it. I survey history and I see in notions of identity little other than ideologies of supremacy or of blood guilt that sooner or later are used to scapegoat whole nations and classes.

Identity is delusion: take its proponents as the false prophets, and the artists who assert role over identity as near as we come to divine—prophetic—correction. The artist is emblematic for all of us precisely because she plays a role, or more than one. Plenty of room still for personality, for what Dylan on the new album calls the immortal spirit.

What we have come to call identity is a kind of idolatry: it looks real but it’s not. But personality is how one uniquely fulfills the role or, as Dylan might say, how you play the cards you’re dealt. In any case, personality is concrete, something you have to work out in fear or in joy. Identity is nebulous, there’s nothing to do with it.

Aren’t they both wearing masks—the actor playing his role and the identitarian in his narrow, empty groove? Where is authenticity? It’s everywhere you put the whole personality into the parts you play. Because personality is something you build, tangible, active, there’s always danger here, too, of idolatry. Dylan knows it, and he sings about this in the Frankenstein-themed “My Own Version of You.” You can also hear that song as a juxtaposition of identity, something assembled from lifeless body parts, with true role, something that can be fulfilled “with decency and common sense… Do it with laughter and do it with tears.”

Jonathan Geltner holds degrees in English and Classics and an MFA in fiction. His translation of Paul Claudel’s Five Great Odes is available from Angelico Press, and his novel Absolute Music is forthcoming from Slant. He teaches at Adrian College and serves as fiction editor at Orison Books. Jonathan lives in Ann Arbor, MI with his wife and two young sons.