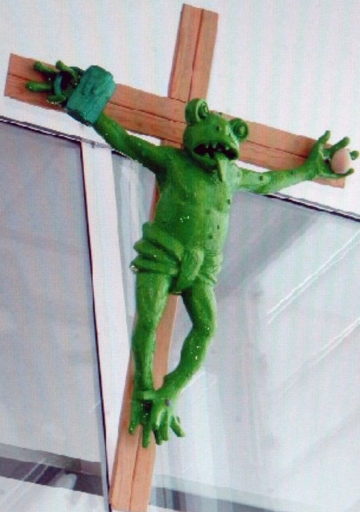

In the year 1990 the German artist Martin Kippenberger made a sculpture, of sorts, that he called Zuerst die Füße, or Feet First. Actually he made five versions of the sculpture, each with slight variations. I’ll concentrate on the green one, since that’s the version I first encountered. I say ‘the green one’ because in different versions of the sculpture, Kippenberger made the frog in different colors: green, blue, silver, purple and brown. The frog in question is a crucified frog. So, the sculpture is a crucifixion scene. A frog on a wooden cross (the sculpture is about four feet tall) with a beer stein in his right hand and, in the green version, an egg in his left hand. The frog is googly-eyed and his tongue is lolling out of his half-opened mouth.

This crucified frog looks like he might have had too much to drink, actually. It’s been suggested, partly by Kippenberger himself, that the crucified frog is something of a self-portrait. That would make sense, since Kippenberger himself was drunk most of the time and died of liver cancer in 1997 at the age of forty-four. He was not, it would be fair to say, in great physical or psychological health in the last years of his life.

Adding more weight to the self-portrait argument is the presence of the egg. Kippenberger was obsessed with eggs and had taken on the egg as something like his own, personal symbol. Why? There’s no easy answer to that question. Mostly, probably, because the egg is so fraught with symbolic meaning on one hand and so simple and even, perhaps, stupid on the other. It’s just a white sphere.

Kippenberger liked to make art that made fun of the act of making art. This contradiction amused him. The very fact that he could make art that revealed something pretentious and silly about making art allowed him to go on, if you catch my drift.

A few years after Kippenberger died, Feet First was on display in a museum in Bolzano, Italy. The sculpture caught the eye of a local politician, Franz Pahl, who condemned the sculpture, calling it a “grave offense to our Catholic population.” Pahl was so upset that he actually went on a hunger strike, ending up in the hospital as a result. This controversy made its way to the Vatican, where then-Pope Benedict XVI pronounced the sculpture blasphemous. The Pope wrote an official letter in support of Pahl and his protest against Kippenberger’s sculpture. Benedict wrote that the artwork, “wounds the religious sentiments of so many people who see in the cross the symbol of God’s love.”

Do people see in the cross the symbol of God’s love? Well, yes, I suppose they do. This would be because of the sacrifice. God, so it is said, sacrificed his only son for our sins. So it is a dignified thing, in a way, this dying on the cross. The early Christians however, were not so sure about this. One is generally crucified because of being a criminal. Dying on the cross therefore brings with it potential shame and ignominy. Which is why it took some time, as the historians of religion explain it, for Christianity truly to adopt the cross as an official symbol. It took some thinking it through, some working it through.

It took the work of embracing a symbol of shame as something strangely potent and beautiful. It took embracing losing as a weird kind of winning. The Messiah does not triumph and become king. The Messiah is executed amongst the rabble. But in doing so, the Messiah validates the rabbliness of the rabble. I am that, says the Messiah. That’s to say, God identifies with and therefore authenticates the actual struggles of everyday life. God ratifies the experience not of those who triumph over the difficulties of life and succeed in their wealth and power but of those who suffer and toil, who can barely make it through. God, to put it another way, sees him/her/itself as a drunken green frog dying horribly with an egg in one hand and a beer mug in the other. For instance.

One can forgive the typically religious-minded person for looking at Kippenberger’s frog and feeling offended. Kippenberger was, obviously, having his fun. He liked to get his tweaks in where he could. But the trick with artists like Kippenberger is in looking past the obvious. Kippenberger makes a joke, always. But he also always makes the joke so that he can get away with a less-obvious sincerity.

Because Kippenberger, especially in his final years of great suffering and physical pain, was obsessed with the condition of mortality, the pathos of living and dying, the drama of it, the ridiculousness of it, the sadness, the horror, and then also, always in everything he did, the final acceptance and the willingness to show us the beauty in all that agony.

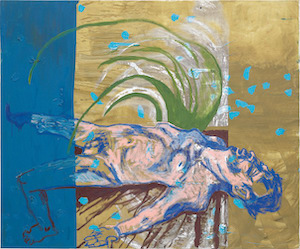

Amongst his last works is a series of paintings he did in reference and sardonic homage to Théodore Géricault’s iconic Raft of The Medusa.  One painting in the series, without a title and made in 1996, depicts a wretched figure in blue, splayed out on some boards, one foot in high-heels, bloated and distended, not long for this world or already having left it. It is a very funny painting, and gut-wrenching at the same time.

One painting in the series, without a title and made in 1996, depicts a wretched figure in blue, splayed out on some boards, one foot in high-heels, bloated and distended, not long for this world or already having left it. It is a very funny painting, and gut-wrenching at the same time.  There is no need to call it a Deposition. But I would call it a Deposition, and a very good one at that.

There is no need to call it a Deposition. But I would call it a Deposition, and a very good one at that.

Morgan Meis has a PhD in Philosophy and is a founding member of Flux Factory, an arts collective in New York. He has written for n+1, The Believer, Harper’s Magazine, The Virginia Quarterly Review and is a contributor at The New Yorker. He won the Whiting Award for non-fiction in 2013. Morgan is also an editor at 3 Quarks Daily, and a winner of a Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant. A book of Morgan’s selected essays can be found here. His books from Slant are The Drunken Silenus and (just published) The Fate of The Animals. He can be reached at morganmeis@gmail.com.